One After Another: Past Temporal Clauses in Russian Posted by Maria on May 2, 2016 in language

In this post, we will look at the ways you can introduce temporal clauses in Russian. We will concentrate on past verb forms. Translations are used to illustrate the meaning of the Russian phrases and may not reflect your local dialect of English.

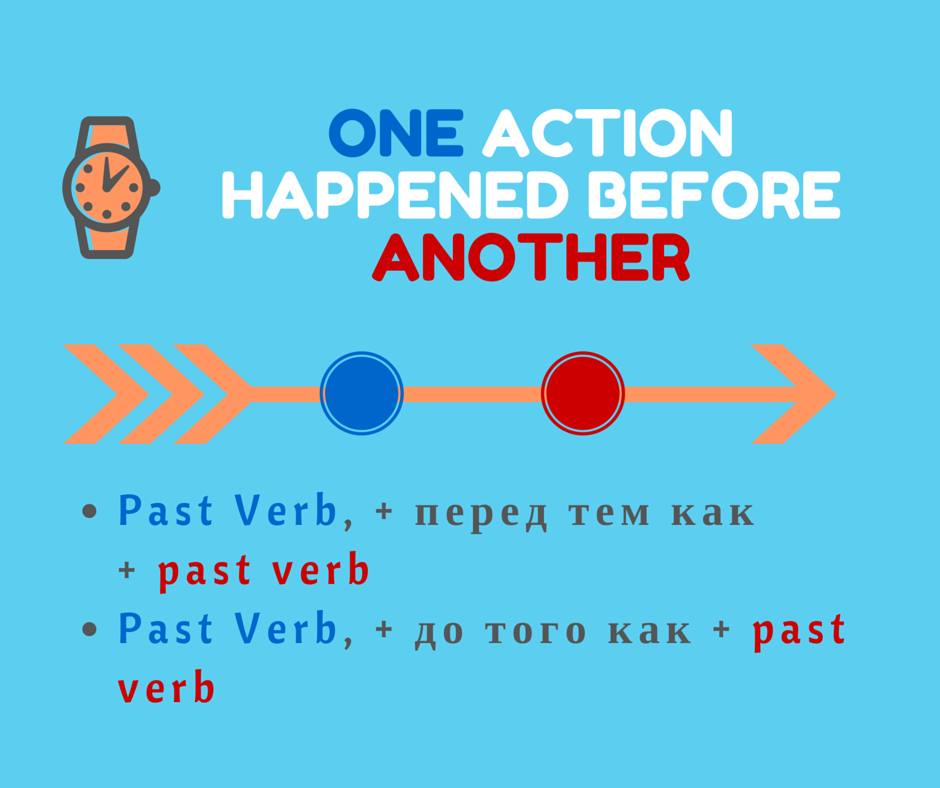

Previous Events

If we want to describe one action that happened before another, we can use the conjunctions перед тем как and до того́ как, both loosely translated as “before.” In terms of punctuation, a comma usually comes before the whole conjunction, although it may come before как. More details on punctuation are available here. Перед тем как is also often used to refer to an action by the same subject that happens before another action.

- Пе́ред тем как но́вые сотру́дники приступи́ли к рабо́те, их поприве́тствовал начальник (Before new the employees started work, they were greeted by their boss).

- Дом, до того́ как его про́дали, каза́лся мне мра́чным ко́рнем несча́стий всей на́шей семьи́ (Before the house was sold, it seemed to me the dark cause of all the tribulations that befell our family). [Марина Палей. Поминовение (1987)]

Note that nouns are preceded by до (before, up until) or пе́ред (before, ahead of). No comma is necessary after the temporal clause.

- До прие́зда уче́ного студе́нты до́лго гото́вили выступле́ния (Before the scholar’s arrival, the students worked on their presentations for a long time).

- Спортсме́ны мно́го тренирова́лись пе́ред ма́тчем (The athletes trained a lot before the match).

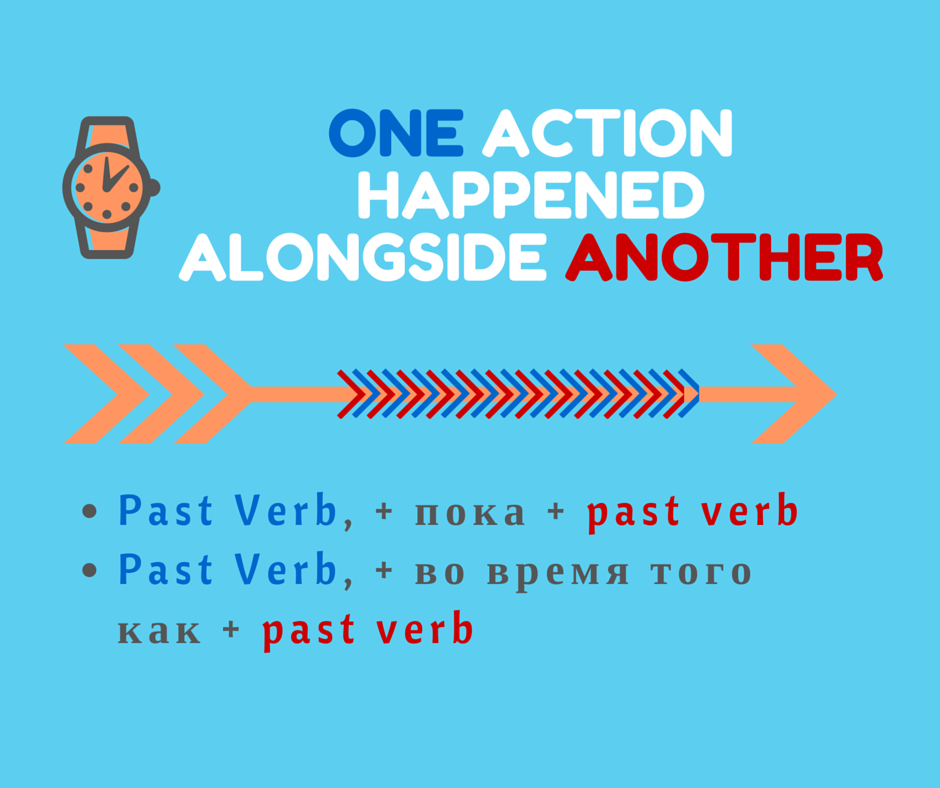

Concurrent Events

If one thing was happening while another was also happening, we can use пока (while) or во время того как (during) to introduce the temporal clause. Both sentences will use an imperfective verb.

- Пока́ мы разгова́ривали, де́ти жда́ли в маши́не (While we were talking, we children were waiting in the car).

- Во вре́мя того́ как худо́жник рабо́тал над карти́ной, к нему́ приходи́ло мно́го посети́телей (While the painter was working on his painting, many visitors came to see him).

Note that if you need to express “during + noun,” use во время + genitive case: Во вре́мя совеща́ния постоя́нно звони́л телефо́н (The phone was constantly ringing during the meeting).

What if one instantaneous action occurred in the middle of another sustained action? In that case, you will use an imperfective verb in the dependent clause following пока́/во вре́мя того́ как and a perfective verb in the main clause:

- Пока́ мы чита́ли ее пе́рвую книгу, она вы́пустила втору́ю (While we were reading her first book, she had another published).

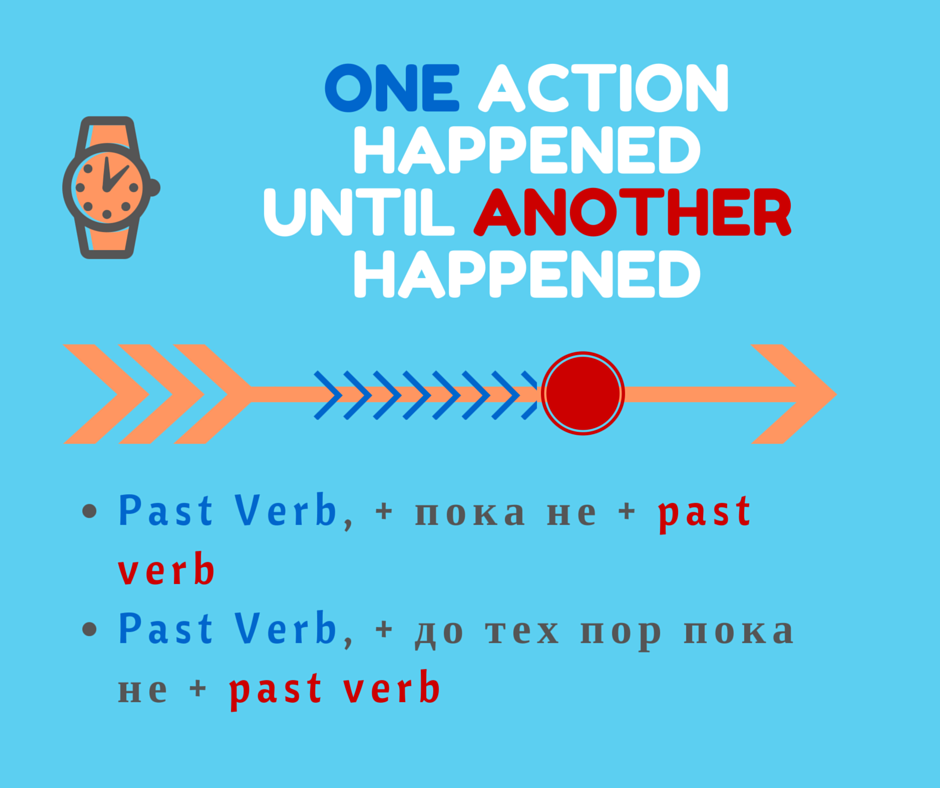

One Action Until Something Happens

You will remember from the point above that while-clauses in Russian can be introduced by пока. The way Russian expresses until-clauses is, literally speaking, “while not” (пока́ не). Note that не does not have to follow immediately after пока́. The dependent clause will have a perfective verb.

- Музыка́нты игра́ли, пока́ не ушли́ после́дние посети́тели (The musicians kept playing until the last visitors left).

- Я люби́ла живо́тных до тех пор, пока́ меня́ не укуси́ла бродя́чая соба́ка (I used to love animals until I was bitten by a stray dog).

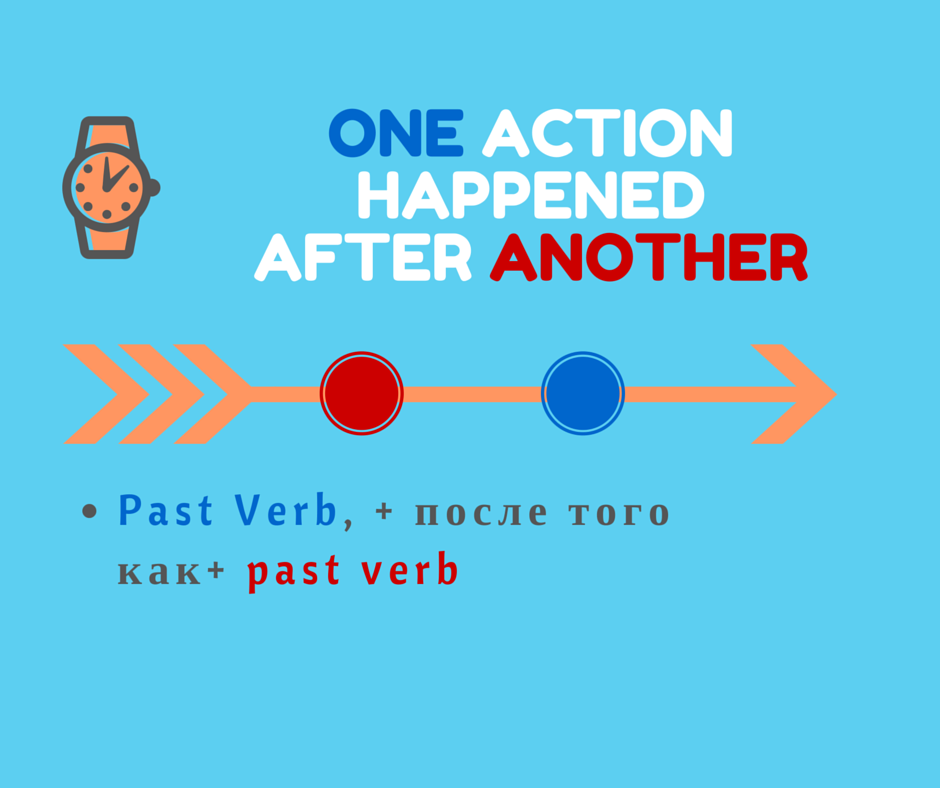

Subsequent Events

Image made with Canva

This scenario is similar to the before-clause. The “change-inducing” or preceding action of the dependent clause is usually expressed by a perfective verb (you could come up with an imperfective example). The verb in the main clause may be perfective or imperfective depending on whether a repeated or one-time action is meant.

- По́сле того́ как писа́тель посети́л Рим, он ча́сто писа́л об Ита́лии (After visiting Rome, the author often wrote about Italy).

- По́сле того́ как певи́ца просла́вилась, ее альбо́мы разошли́сь огро́мным тиражо́м (After the singer became famous, her albums sold a lot of copies).

Когда-clauses

One final note concerns the conjunction когда́ (when). The sense of the sentence is largely defined by the verb aspect (perfective/imperfective). “Когда + imperfective, perfective” refers to one action that occurs in the middle of another or interrupts it:

- Когда́ я жила́ в А́встрии, я познако́милась с Фре́йдом (While I was living in Austria, I met Freud).

“Когда + imperfective, imperfective” refers to two concurrent actions, similar to пока, or repeated actions:

- Когда́ мы ложи́лись спать, ма́ма расска́зывала нам ска́зки (When we would go to bed, our mother would tell us fairy tales).

“Когда + perfective, perfective” refers to two consecutive actions, just like после того как:

- Когда́ мой брат око́нчил шко́лу, он поступи́л в институ́т (After graduating [from] [high] school, my brother went to university).

What aspects of temporal clauses do you find logical/confusing/fascinating? What other scenarios would you like to have covered here? Obviously, this post only touches upon certain structures and omits others, and there is much more to be added!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Fan:

Nice colorful pics!

Maria:

@Fan Thank you — I hoped visuals would help illustrate sequences of events.

Richard:

A great post, Maria!

I have one question just off the top of my head. You’ve given several examples showing two different ways of expressing one action in relation to another action. How do we go about choosing which way to use? For example, what is the difference between пока не and до тех пор пока не? Is it purely a question of writing style?

Maria:

@Richard Thank you, Richard.

I would say the shorter expressions are more colloquial (they are perfectly acceptable in writing, though) and the longer ones tend to be more bookish or official-sounding. One situation where you would choose the longer conjunction is when you need to emphasize its literal meaning.

For example, пора means ‘time,’ so ‘до тех пор, пока’ means ‘until the time when.’ Perhaps you want to underline the ‘time’ aspect, as in ‘Мы не уйдем до тех пор, пока не будут выслушаны наши требования’ (We will not leave until the moment our demands have been heard).

I hope this helps!

Peter Ellis:

Brilliant Maria – this is exactly the sort of thing that us learners need.

I personally find using all these small words (conjunctions?), like ‘тем’, ‘того’ and ‘как’ quite difficult but can see they would make me sound more Russian if I used them. But, being lazy, I bet I’ll fall back on simply ‘когда’ and hope I get the verb form correct!

In the first case (one action happened before another), am I right in saying ‘до’ would be followed by the genitive case and ‘перед’ by the instrumental?

I wonder if we could have something on – not sure how you would describe them – interjections and qualifications, things like ‘by the way’ or ‘in case’ and ‘as long as’ … the sort of stuff that modifies or qualifies what we say?

Thanks once more.

Peter

Maria:

@Peter Ellis Thank you, Peter.

I see what you mean about the difficulty of keeping all the conjunctions straight. To let you in on an open secret, Russian tends to favor temporal modifiers over subordinate clauses where possible. So the more likely way a Russian would say “After the story came out, people talked about it for months” is “После выхода этой истории о ней говорили несколько месяцев.”

You are correct about the noun cases: до is followed by the genitive, and перед is followed by the instrumental.

Good ideas for a new post — I’ll put them on my list!

Joerg:

This is a really great post, Maria. Thanks a lot for your efforts.