Reading for/about the Sick: «Униженные и оскорблённые» [The Humiliated and Insulted] Posted by josefina on Nov 17, 2009 in Uncategorized

Though I am still not entirely «здорова» [healthy] yet, today I «чувствую себя гораздо лучше» [feel much better] than the days before and that’s why I finally have enough strength to write a post. I was «очень тронута» [very touched] by all of your kind wishes of health and for me to get better soon, which is why I think I’m improving as fast as I am! «Болеть» [being sick] is, as we all know, one of the most boring situations a human being can be in. When you’re sick you can’t really do anything at all, except stay in bed and try to sleep as not to let the fever get the best of you. But when you’re sick you can also «читать книгу» [read a book], because reading books are very easily done when in bed. The problem is what book to choose. My choice was the only novel written by «Фёдор Михаилович Достоевский» [Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky] that I haven’t actually read before: «Униженные и оскорблённые» [“The Humiliated and Insulted“]. Before this I had already managed to read everything by Dostoevsky, some novels even twice (either both in Swedish and Russian or both in English and Russian) wrapping it up about a year ago with «Подросток» [“A Raw Youth“]. Do not let this surprise you, though – after I first read ‘Dusty’ (as I like to call him after the Allen Ginsberg poem) at the age of 18 I managed to swallow almost everything from «Бедные люди» [“Poor Folk“] to «Братья Карамазовы» [“The Brothers Karamazov“] within a year in different translations. Somehow I never got a around to «Униженные и оскорблённые» [“The Humiliated and Insulted”], even though I tried once to read it in an English translation when I was also sick – I was 19 at the time and living in Saint Petersburg. But I couldn’t do it. The book was too full of «болезнь» [sickness] for my taste back then and I put away the book for good after about a 100 pages.

Five years later I picked it up again and this time I found it relieving to read about all these «нездоровые» [unhealthy] people in Saint Petersburg back in the 1800’s. Everyone in this book «болеет» [is sick/ill]. On every page you find things like: «Я сделался больной» [I became sick], or «Она похудела» [She had lost weight], or «Он побледнел» [He had turned pale], or «Она была в бреду» [She was delirious], or «Он хворал» [He was ill/sick]. The imperfect verb «хворать» [be ill, be sick] is old and thus used in modern Russian language mostly when talking ironically of disease, but back in Dostoevsky’s days this verb wasn’t old at all (or not AS old anyway) and that’s why when he uses it then it is without any irony. Reading about other sick people when you are sick yourself is refreshing and you feel like you’re not alone at all but part of a world filled with other sick people also going through fevers and pains. But then again, I’m still in a town «в карантине» [in quarantine] and around me are thousands of other sick people so why I am feeling alone? Because you don’t really get to meet any other sick people when you are yourself sick…

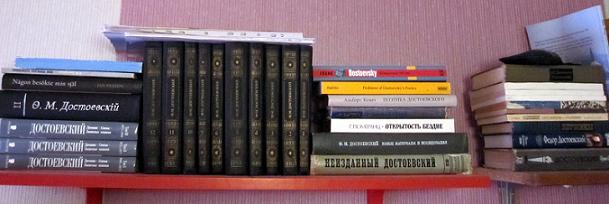

Meet my «полка с книгами Достоевского или о Достоевском» [bookshelf with books by Dostoevsky or about Dostoevsky]. It used to be ONE bookshelf, anyway. As you can see clearly on the picture above, «великий русский писатель» [the great Russian writer] has started to spread to other book shelves…

Let me tell you something about Dostoevsky. Judging from what I’ve got by him and from what I’ve read of him and about him and the fact that I’ve translated him and written a BA thesis on him and even worked «в музее Достоевского в Омске» [in the Dostoevsky Museum in Omsk], I think I know a thing or two about him. When dealing with Dostoevsky you should know this first of all: «Фёдор Михаилович жизни-то не изобразил» [Fyodor Mikhailovich didn’t portray life]. If you think you’ll find «реализм» [realism] when opening up a copy of «Записки из подполья» [“Notes from Underground“] then you are sorely mistaken. Dostoevsky called what he wrote «фантастический реализм» [fantastic realism] but that was not really what he was about anyway; what he wanted to do was «найти в человеке человека» [to find in the human being a human being]. That’s why we shouldn’t get hung up on small details in his novels that are unrealistic or seem illogical. Let’s take “The Humiliated and Insulted”, for example, since I’ve just finished reading it. This book could also be called “Much Ado about Nothing” (perhaps Dostoevsky knew this title had already been used before him in world literature). In this book not a single character work as much as a day – if you don’t count the main hero when he’s writing his books – but keep going around to each other to solve problems that seem unsolvable to them, but not to the reader.

«Униженные и оскорблённые» is a novel about highly complicated «личные отношения» [personal relations] between a small group of people related to each other in one way or another. The main hero is «Ваня» [Vanya], a young writer that has just had a big success with his first novel, despite being chronically ill and already early on in the novel he declares that he is dying (but then does not mention it anymore). Vanya is in love with «Наташа» [Natasha], a girl together with whom he grew up in the country side before going to Saint Petersburg to study. Natasha is in love with «Алёша» [Aljosja], the stupid and rather thoughtless son of «князь Валковский» [prince Valkovsky]. Prince Valkovsky used to be good friends with Natasha’s parents, «Ихменевы» [the Ikhmenevs], and they also worked for him but now they are in a fight over some money and that’s why they have all left the province for Saint Petersburg in order to settle their differences.

The novel begins with how «Ваня» [Vanya] becomes witness to how the old man «Смит» [Smith] with his equally old dog «Азорка» [Azorka] die in public and decides to move into the old man’s apartment. At this apartment his grandchild «Нелли» [Nelly] shows up one day. Nelly is also chronically sick with epilepsy and living under awful conditions with drunkards and so Vanya saves her and as he tries to do so he runs into his former classmate «Маслобоев» [Masloboev] in the street – who is very drunk also, but decides to help Vanya save Nelly. Nelly turns out to be the daughter of «князь Валковский» [prince Valkovsky], who before both «унизил» [humiliated] and «оскорбил» [insulted] her mother even though he was officially married to her and stolen a large amount of money from her, causing her to die «в чахотке» [in tuberculosis] «в подвале» [in the basement] without any money and leaving her daughter to beg on the streets for food. Prince Valkovsky is not bothered by this at all, and in his evil, selfish and disgusting character we can see how Dostoevsky is beginning to work his way artistically toward such unforgettable bad guys of his like «Свидригайлов» [Svidrigajlov] in “Crime and Punishment” and «Ставрогин» [Stavrogin] in “The Devils”. Prince Valkovsky is never accused of sexually abusing under-age girls in the book – which is the ultimate crime in the world of Dostoevsky, the only crime you are never forgiven – but toward the end we are informed that he recently got engaged to a fourteen year old… Before this he tries desperately to get his foolish son Aljosja away from the poor Natasha, and thus hooks him up with the wealthy young girl «Катя» [Katya]. Aljosja proves his lack of stamina by dating both girls and also visiting some prostitutes in-between hiss two women and after always coming home to Natasha to fall at her feet and beg her forgiveness… In the end of the novel everyone is recovering from the humiliation and insults, and gaining back all the weight that they lost during the 1,5 year that the novel took place and during which they were all suffering from various diseases. Except for epilepsy Dostoevsky is not the kind of writer to specify just exactly what his characters have come down with.

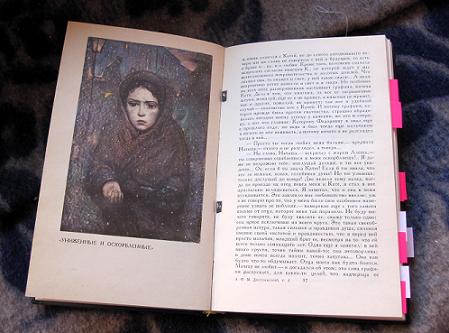

An illustration of «Нелли» [Nelly] from the book in a collection of Dostoevsky’s works in 12 volumes published in 1982. Why is it that I can’t read a single book without it ending up looking like this – filled with post-its?!

When we’re talking Dostoevsky we must never forget that no matter how unrealistic his artistic world is, he is first and foremost «христианский писатель» [a Christian writer]. That’s why the key to understanding his sometimes feverishly strange yet wonderfully captivating dialogues between people over vodka in different questionable establishments is to always keep an eye on where he puts «Новый Завет» [The New Testament]. In this novel it turns up early on in the apartment of the old man Smith, and was the book that he used to teach Nelly. In the culmination of the novel Nelly brings up the Good Book again, and the part quoted is how Jesus said «прощайте обиды» [forgive insults] and that’s when we realize what this book is about: «прощение» [forgiveness]. In the same way we can easily come to terms with “Crime and Punishment” by looking at what chapter Sonya reads to Raskolnikov. Remember Lazarus? Yes, of course you do, and then it is no surprise to you that this is a novel about «воскресение» [resurrection]. Putting things simply – Dostoevsky didn’t think outside the box, i.e. the Bible; he only thought inside the box. Think this somewhat limited his chances of reaching a broad audience world-wide? Well, not really. Despite claiming to rather want to ‘stay with Jesus, if Jesus is outside the truth, than with the truth’ Dostoevsky did well as a writer and succeeded in becoming the most influential 19th century writer in the 20th century.

Did you know that The Old Testament is called «Ветхий Завет» in Russian? I got this question on an exam once, and after answering it correctly the professor was so impressed that he decided not to ask me anything else. Just thought I could give someone else this tip!

Now I’m off to bed once again…

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Bruce Dumes:

What an interesting post! Many concepts in Dostoevsky have always been difficult for me because of my lack of familiarity with the «Новым Заветом» because I am Jewish. I’ve also had this issue reading James Joyce and Samuel Beckett, with whom Catholic philosophy is so deeply imbued. I watched the Russian film «Остров» and found it difficult to understand until I sat down with a Russian who explained the peculiarities of the Russian Orthodox priests. Thank you, Josefina! Ещё раз, будь здорова!

Erin:

Josefina,

Thanks for taking the time to write this blog (even while you’re sick). I VERY much enjoyed reading your synopsis of this Dostoevsky novel. I also hope that you feel 100% better soon!

Вечный Жид/Den Vandrande Juden:

Burce, there’s nothing stopping Jews from reading the New Testament! You’re not going to de-Jew yourself by doing so. 😉

Remember, the Gospels are books about a Jew written by Jews. Jesus was born and died a Jew. If Jesus had been alive in Germany during WWII, he would’ve wound up in the gas chambers along with all the other Jews.

More importantly, studying the New Testament, will give you insight into the themes of Dostoevsky’s novels. Josefina mentioned forgiveness as one, but that’s not really accurate. To really understand Dostoevsky, you have to understand that all his novels are really about only one thing: redemption. Forgiveness is a mechanism through which his characters achieve redemption, but it’s the redemption which is important. Forgiveness in and of itself isn’t that interesting. It’s the object of the forgiveness, the redemption made possible in the person being forgiven by that forgiveness, that’s at the heart of Dostoevsky’s novels, and — not coincidentally — at the heart of the story of Jesus (i.e., Jesus had to die in order to redeem humanity for its sins).

I’m not a Christian, by the way, so don’t think I’m trying to proselytize anyone here.

Anyway, Josefina is right when she says that Dostoevsky is first and foremost a Christian writer, so anyone who wants to read him should be very familiar with the New Testament, specifically in the context of Eastern and then Russian Orthodoxy.

Incidentally, calling it the “Old Testament” is an inherently supersessionist term and therefore kind of insulting to Jews. There’s nothing “old” about the Tanakh to them. 😉

Josefina:

Hi, Den Vandrade Juden! What I said about forgiveness here should not be seen as if this is the main theme of ALL Dostoevsky’s novels, but this one in particular. I agree that redemption is of course a theme that goes for much more of his novels than just this one book. Dostoevsky was most diverse in his usage of both New and Old (*wink wink*) Testament. For example, if you consider the book of Job in the context of his “The Double” you’ll see that the form for the dialouge within ‘gospodin Golyadkin’ and also between him and his ‘double’ is very similair to the dialouge between Job and his friends and between Job and God.

Maybe I’m supressionist and also insulting Jews when I call it the “Old Testament” but that’s my choice. I make this choice since this makes it easier for me to keep the two books apart… Perhaps I should switch to calling them Torah and the Gospel instead? Would that be less supressionist and insulting?

Вечный Жид/Den Vandrande Juden:

I wasn’t referring to *your* use of the term “Old Testament” — you didn’t invent it, after all. (Or did you? 😉 )

I was just commenting on the fact that the term itself is a problematic one, in the context of what I said about Jews reading the Christian Bible. Sorry if I was unclear. Obviously, “Old Testament” is the generally accepted term, and barring any kind of serious historical reevaluation among Christians, it’s the term that’s going to stay.

Incidentally, “Torah” is only the first five books of the Old Testament, which are also known as the Pentateuch (Greek for “five parts”), and also known as the “Five Books of Moses,” since they were supposedly all written by Moses (which would be believable if they didn’t describe Moses’s death…).

Similarly, the Gospels are only the first four books of the New Testament.

For the very politically correct (which I am not, particularly), “Hebrew Bible” or “Tanakh” are the accepted terms for the Old Testament. Tanakh is a Hebrew acronym for the three categories of books in the OT — Torah (“teachings” — cosmogony, laws, history), Neviim (“prophets” — like Isaiah, Daniel, Ezekiel, etc.), and Khetuvim (“books” or “writings” — includes things like Ruth, Esther, etc.).

One interesting thing is that there are books that are not part of the Western (=Roman Catholic/Protestant) Canon, but are part the Eastern Canon, and therefore inform Dostoevsky’s writing but are unknown to people in the West (including the historically Lutheran Swedes). These books are called “apocryphal” or “deuterocanonical” and include Tobit, Esdras, and other books as well as expanded versions of books which are part of the Western Canon, such as Daniel, which, in the East, includes very interesting stories like Bel and the Dragon, and the story of Susanna, which is fascinating. An American poet named Wallace Stevens wrote a poem called “Peter Quince at the Clavier” about the story of Susanna. I think it’s on Wikipedia. It’s a beautiful poem.

One interesting consequence of Dostoevsky’s popularity and influence in the West in the 20th century is that you see the introduction of typically Eastern and Russian Orthodox themes into artistic production in countries where those themes would ordinarily be totally foreign, like in the movies of Ingmar Bergman (“Winter Light” is about a country priest wrestling with his loss of faith) and even Akira Kurosawa (“Drunken Angel” is a very Dostoevskian story of redemption — he also made a movie version of “The Idiot”).

Anyway, I hope you get better soon.

Vanessa:

I’ve only read “Crime and Punishment” so far, but this post has interested me in reading more of Dostoevsky’s works. Maybe I could even try some in Russian . . . .

Sr Maria:

I am so happy to hear that you are feeling much better! And congratulations on two years of blogging! You are a terrific teacher and I hope you will continue helping us Russian students.

Thank you for sharing your insights about Dostoevsky. I think you are right on target that he was most concerned about the human person and wanted to portray what makes man to be fully a human person. And that is the effects of divine grace on the person, the acknowledgement that one is indeed a sinner and in need of God. Maybe you are familiar with the Russian concept of Умиление? I am thinking here of its ancient use, in the religious sense, which is a feeling of deep repentance and conversion and realization that God is working a transformation in the person. (called divinization, i.e. the person is made by grace more like God.) Some translate it as that feeling which comes in the encounter between the heart and divine grace. This is very popular in books such as The Pilgrim. (Lord Jesus Christ, be merciful to me, a poor sinner!)

Marcia Shehorn:

I also delight to hear that you are starting to feel better (although by this time, you are probably well, since I see there’s already another Blog for me to read). Just to respond to your comment about the Old Testament not being смарый or even в смарину, but ветхий: if you look in the New Testament book of Hebrews, which is a book written to Jews who had embraced Jesus as their Messiah, in the 8th chapter, verse 13, it says that the new covenant (завем) made the old one obsolete (усмарелый), an even clearer picture of the contrast than ветхий. This does make believers supersessionists, as the new supersedes the old.

Den Vandrande Juden:

It would be interesting to find out if ветхий meant “dilapidated/ragged/worn-out/shabby” when it was chosen as the translation for “Old Testament.”

The purpose of Hebrews is debated, by the way. It might’ve been part of the discussion out of which came the very convenient Pauline faith-not-works workaround for converts.

Marcia Shehorn:

oops!

I used the м instead of the т going out of cursive.

“старый” and “устарелый” is what I meant!

Sorry— I must be getting старый.