You say it best when you say «ничего» [nothing] at all Posted by josefina on Jul 30, 2010 in language, Russian for beginners, Russian life, when in Russia

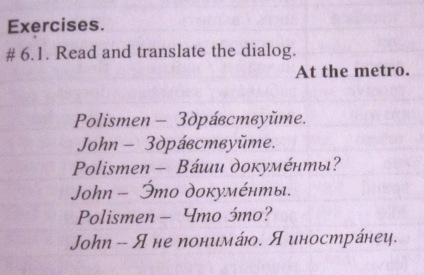

Let’s put an end to this kind of boring (and pointless and not to mention plainly weird) conversations frequently used in textbooks on Russian language! Wouldn’t it be much more fun if the policeman had said: «Ну что это?» [Well what is this?] and John at that had answered: «Я вообще не понимаю. Я типо иностранец» [I totally don’t get it. I’m like a foreigner].

How often do you start a sentence with «знаешь…» in Russian – or with the equivalent “you know…” in English? How many times a day do you find yourself commenting on something interesting by using only «вот» [which could be translated when used in this context as ‘so there we are’ or ‘that’s the way it is’]? Are you also the kind of person who prefers to express doubt or disbelief in dialogue by saying «ну» [well] with a long and stressed «у»-sound (making it sound like «нуууу»)? If you are, then you’re welcome to join the club of the rest of us humans! Such small words like the ones mentioned above are known in English as discourse particles, or more commonly fillers – and that’s exactly what they’re meant to do in every day speech: to fill up the space between ‘real’ words that actually have some sort of meaning. Some people frown when others frequently exclaim «вообще!» [‘totally!’; the correct pronunciation in this context should be «ваащее!» with both vocals rather extended in length, even though only the «е»-sound is stressed and thus also a little bit longer] instead of making the effort to come up with a positive reaction that’ll actually contribute to the conversation. I’m not one of those people. I love fillers! I’m so fond of fillers that I frequently come up with new ones in all three languages in which I’m fluent and then there are some favorites that I rotate with time. But most of the time I start all of my conversations – be it in Russian, English, or Swedish – with «знаешь…» [you know…], even though the people I’m talking to obviously don’t ‘know’ – or else I wouldn’t have to talk to them in the first place. Starting by saying that someone ‘knows’ when they don’t know at all is the first rule of using discourse particles: it is imperative that they be completely and utterly pointless.

For a word to qualify as a filler it has to completely lack semantics in the context where you say, hear or read it. For example, like the nonsensical meaning of the word «типо» [‘like’] in the following sentence:

«Он типо мимо прошёл» [He like walked past].

You might as well have left this word out of the sentence entirely; the meaning doesn’t depend on it the least. «Типо» [‘like’] can also be used in colloquial Russian to give the listener a warning that what is about to follow after it is a quote, i.e. something said by someone else at an earlier point in time. Let’s have a look at how this might sound:

«Он типо я тебя люблю» [He was like I love you].

Another way of saying the same thing – and, some might argue, the correct and thus ONLY way – is:

«Он сказал, что любит меня» [He said that he loves me].

I don’t believe that there’s only ONE correct way of saying something and that’s why I don’t understand why discourse particles are called «слова–паразиты» [lit. ‘words-parasites’] in Russian. The word «паразит» [parasite] is such a negative way of looking at them. The phenomenon of «слова–паразиты» [‘words-parasites’] is not solely «отрицательный» [negative] and that’s why I’d suggest we call them «дискурсные частицы» [lit. discourse particles] also in Russian language. Russian grammar uses the word «частица» in the same meaning as the English word particle. Of course, discourse particles are not utterly harmless. Sometimes they can – and indeed they do – get on your nerves. When I was studying in Russia there was a girl in our group who would start every sentence with «собственно говоря…» [strictly speaking…] and sometimes she would build up whole arguments solely around frequent repetitions of this one phrase. The result was that I didn’t understand anything of what she was trying to say; only later was I informed by the other Russian students that this was her specialty – her way to make the professors think she was actually making a point even though she had no idea what she was talking about… For her it worked «блестяще» [brilliantly]: she was a straight A student. For me listening to her was a test of my «терпение» [patience] every time she spoke in the classroom, so much that I would sometimes mumble to myself: «“говоря” есть, а где “собственно”?!» [“there’s ‘speaking’, but where is ‘strictly’?!”].

Fillers can be used in several different ways – not only to fool professors into thinking you know something that you haven’t got a clue about. The key to start using them every here and there is to know which they are and what they mean. Once you got that down you should be fine contaminating your «великий и могучий» [‘great and mighty’, i.e. Russian language] on your own with any parasite-words of your fancy. And that’s why I’ve collected some of the most common Russian discourse particles in this list below (you can thank me later) together with examples on how to use them in sentences. I am aware of the fact that ‘correct’ Russian spelling demands me to place commas before and after each discourse particle, but because I wanted to keep these sentences looking like they sound I didn’t. Just so you know!

«гм…» [er…]:

«Ты гм уже гм купил такую гм штучку?» [You er already er bought that er thing?]

«вообрази(те)…» [fancy…; just imagine…]:

«Он вообрази взял и записался на курс фламенко» [He just imagine went and signed up for a flamenco course].

«понимаешь…» [you know…]:

«Я понимаешь не знал, что сказать ему» [I you know didn’t know what to tell him].

«значит…» [so…; then…]:

«Мы значит были на даче всё лето» [So we spent all summer in the dacha].

«кстати…» [by the way…]:

«Она кстати мне так и не позвонила» [She by the way didn’t call me].

«допустим…» [let’s suppose…; say…]:

«Вчера мы допустим купили бы два билета вместо троих» [Yesterday we would’ve bought say two tickets instead of three].

«так…» [so…]:

«Так ты понял меня?» [So you understood me?]

«так сказать…» [so to speak…]:

«Вера так сказать поступила в докторантуру» [Vera so to speak got accepted to the doctoral program (or: graduate school)].

«что называется…» [as they say…]:

«Мы что называется приобрели кошку» [We as they say got ourselves a cat].

«прямо скажем…» [let’s be frank…]:

«Это прямо скажем нелегко переплыть через Атлантику» [It is let’s be frank not easy to cross the Atlantic Ocean (by some kind of boat, or – let’s go wild – to swim across it)].

«не поверишь…» [you won’t believe it…]:

«И он не поверишь спросил не хочу ли я за него замуж» [And he you won’t believe it asked me if I wanted to marry him].

«между прочим…» [incidentially…]:

«В прошлом году я его между прочим два раза встречала в синагоге» [Last year I incidentially met him two times in the synagogue].

«по правде сказать…» [to tell the truth…]:

«И мы по правде сказать не сошлись характерами» [And we to tell the truth didn’t get along (or literally: ‘our characters didn’t agree with each other’)].

Using fillers like this is another way of saying «ничего» [nothing] at all. Or – which is perhaps an even better way of putting it – what you say when you’re not saying anything at all. Which Russian discourse particles do you like the most? Which ones do you find yourself frequently using? Which ones would you like to get rid off?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Throbert McGee:

“He just imagine went and signed up for a flamingo course.”

Значит, он получил от Червонной Королевы приглашение на крокет с ёжиками? ;-D

(You mean he got an invitation from the Queen of Hearts to play hedgehog-croquet?)

josefina:

Throbert: Yes, of course THAT was what I meant! Doesn’t everyone take flamingo courses these days? It’s all the rage in the Urals 😉

Okay, so I made a mistake. I meant flamenco! Please don’t shoot me, I’ll fix it right now.

Throbert McGee:

(In English, “flamenco” is a Spanish dance; “flamingo” is the big pink bird)

josefina:

Okay, Throbert, point taken: I corrected the mistake and even linked the Spanish dance to wikipedia for those interested to find out more about it 😛

Throbert McGee:

Sorry, I should’ve updated the page before I made my second post!

Minority:

As I know, we call such words “слова-паразиты” not only because they’re really bad (though when one use ’em in each sentence, it really sounds awful). It’s something like that: you easily can be used to word or phrase, and then start to use it often, and you may even do not notice it at the first time. And it’s hard to stop use it. And the same with паразит – it’s enough to eat bad food just once, and then you should work hard to heal yourself from паразиты.

As for me, i often use: “хм”, “ясно”, “ага”, “эээм”, “значит”, “кстати”, “случайно”

Liz:

I have been studying Russian for three years here in America. Once a week I meet with a Russian woman to help her study for her US citizenship test. About every three minutes she says допустим. Hey, I finally know what she’s talking about! Thanks!

Steve:

You might be interested to know that in Spanish the word *flamenco* can denote either the dance or the bird! Both words are derived from the Spanish word for “Flemish.”

Ксения:

Есть ещё много слов-паразитов

Например: Прикинь, Короче, дак вот…

И кстати, у вас в русских предложениях пропущенно много запятых…Например вот это предложение:

[И он, не поверишь, спросил, не хочу ли я за него замуж]

Четырёх запятых нет 🙂

Minority:

Ксения, мне кажется, даже грамматику русского языка иностранцам выучить трудно, что уж говорить о пунктуации. К тому же, насколько я знаю, в английском языке пунктуация не имеет того же значения, что в русском, поэтому им трудно представить, что запятая может совершенно изменить смысл фразы. 🙂

src:

Coincidentally, we also have a filler “tipo” in Portuguese (though it’s not as “versatile” as “like”/”типо”, apparently).

Oh, great blog, by the way.