Calligraphy (书画) Posted by Stephen on Sep 28, 2011 in Culture, Uncategorized

Chinese calligraphy or 书画 (shū huà) stands as a testament to evolution of the Chinese written language. Learning it takes years of practice, a steady hand, and an intense focus to detail that few can master. Chinese calligraphy is both extremely fluid and extremely structured. A missed angle, a frayed brush tip or even a couple extra grams of applied pressure and your masterpiece is no more. Like basic Chinese written language, calligraphy navigates the dichotomy between function and form.

Chinese calligraphy or 书画 (shū huà) stands as a testament to evolution of the Chinese written language. Learning it takes years of practice, a steady hand, and an intense focus to detail that few can master. Chinese calligraphy is both extremely fluid and extremely structured. A missed angle, a frayed brush tip or even a couple extra grams of applied pressure and your masterpiece is no more. Like basic Chinese written language, calligraphy navigates the dichotomy between function and form.

Instead of using a syllabic system that represents sounds, Chinese written roots are pictographic in nature. Memorization and recognition of key characters are the secret to unlocking the Chinese language, requiring a mix of right brain pattern understanding and left brain logic (Click here for a post on Right Brain + Middle Language = Chinese).

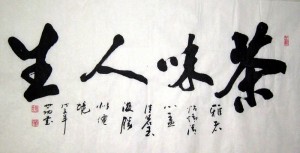

At the highest levels, Chinese calligraphy often falls into two categories: 1)writing as a practiced skill, similar to penmanship or 书法 (shū fǎ) and 2) as a form of art or 艺术 (yì shù). True calligraphy masters are able to tightrope walk this fine line between propriety and beauty.

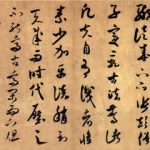

While calligraphy has extended to many Asian nations (including Japan, Korea, and Vietnam), calligraphy’s origins date back to Ancient and Imperial China. Styles include cursive, handwritten and even print generated forms. Calligraphy also includes many landscape styles of paintings, usually with bamboo plants, mountains, rivers/lakes and birds. However, the most prevalent form of calligraphy is character based.

In pre-modern times, a scholars calligraphy skills were highly valued and prized among intellectual classes and nobility. Today however, calligraphy is most popular among artists and hobbyists, but has disappeared from most educational settings. So here are some basics on calligraphy to get your started:

Stroke Order (笔顺):

Correct strokes, known as “stroke order” or 笔顺 (bǐ shùn) are essential to Chinese calligraphy. This is because it sets the character structure, balance, and rhythm of the writing. Further, because some forms of Chinese calligraphy are long, continued strokes (similar to cursive), proper stroke order is required to understand the character. In the twentieth century, simplification of Chinese characters took place in mainland China, greatly reducing the number of strokes in some characters, and a similar but more moderate simplification also took place in Japan.

Click here for more comprehensive guide on Chinese stroke order.

Tools and Setup:

The tools needed for Chinese calligraphy are quite basic, but tradition is important. An ink brush or 毛笔 (máo bǐ), ink or 墨水 (mò shuǐ), paper or 宣纸 (xuānzhǐ), and inkstone or 砚台 (yàntái) are all essential parts calligraphy. In fact, they are known together as the “Four Treasures of the Study” or 文房四宝 (wénfáng sì bǎo) in China, and as the Four Friends of the Study elsewhere.

Ink must be consistent and not too thick or thin, requiring the artist to grind his or her own ink into the ink stone by applying water. You must also wick the brush tip and keep the paper perfectly flattened. From there it’s all up to you. Just practice, practice, practice!

Calligraphy vocabulary (书画生词):

宣纸 (xuānzhǐ): paper specially used for calligraphy

Follow Steve on twitter: @seeitbelieveit

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Stephen

Writer and blogger for all things China related. Follow me on twitter: @seeitbelieveit -- My Background: Fluent Mandarin speaker with 3+ years working, living, studying and teaching throughout the mainland. Student of Kung Fu and avid photographer and documentarian.

Comments:

Steven C. Poling Jr.:

You should have a follow-up piece on different Chinese fonts (e.g. 楷书、小篆、大篆、隶书、行书、草书、等等)。

Steve:

@Steven C. Poling Jr. Great Idea, Steven. We’ll get on that.

-S