The Dutch Resistance in World War II – Part 3: Het Verzet Posted by Sten on May 23, 2019 in Culture, Dutch Language, Dutch Vocabulary

In the aftermath of the dodenherdenking and the celebration of the bevrijding of the Netherlands from the German occupation during World War II on May 4 and 5 and the fact that 2019 marks 80 years since the start of World War II in 1939, I am writing a series on how the Dutch got sucked into the war, and how they fought and resisted the Nazi occupation. In this third part, we will explore how the Dutch resisted the Nazi rule.

Other posts in the series:

The Dutch Resistance in World War II – Part 4: De Engelandvaarders

What is Het Verzet?

After the capitulatie (capitulation) of the Netherlands, many people did not want to give up that easily. Some actively collaborated with the Nazis, an act known as collaboratie (collaboration). Others simply tried to make the best of the new situation without resisting or helping it actively, while others actively resisted it. This last group would become known as het Verzet (“The Resistance”). While this sounds like one coherent, large group, it really was not. In fact, the question that should first be asked is: wat is verzet (what is resistance?)

Geschiedschrijver (historian) Loe de Jong, who wrote a seminal series on the Netherlands during World War II, defines verzet as follows: “Verzet was steeds verzet tegen de bezetter: elk handelen waarmee men trachtte te verhinderen dat deze de doeleinden verwezenlijkte die hij zich gesteld had.” (Resistance was always resistance against the occupier: Every action with which one intended to prevent that the occupier would realize the objectives he had set.) These doeleinden were, in particular:

- To make the Netherlands a nationaal-socialistische staat (national-socialist state)

- To use the Dutch economisch potentiaal (economic potential), in particular for the oorlogsvoering (war effort), or simply exploitatie (exploitation)

- To deport hundreds of thousands of Dutch staatsburgers (citizens), in particular the Joden (jews) to concentration and extermination camps, or simply deportatie (deportation)

- To prevent any steun (support) for vijanden (enemies) or any actions against the three doeleinden above.

With this broad definition, many acts were considered verzet. Something seemingly harmless like wearing an anjer (carnation) on June 29, 1940 – the verjaardag (birthday) of Prince Bernard, whose favorite flower was the anjer, was already considered verzet. Why? After the Germans took over, the koningin (queen) fled to England. The monarchie (monarchy) was removed when the Nazi rule took over. So showing allegiance to that monarchie meant going against the first doeleinde of making the Netherlands a nationaal-socialistische staat.

Of course verzet would also go further, like giving a place to onderduiken (hide) to Jews or other vervolgden (prosecuted) under the Nazi regime. Or much further, like executing Nazi officers or attempting to assassinate high-ranking officials. Many verzetsstrijders (resistance fighters) were much more terughoudend (reluctant) to do these things, because the repercussions were grave. If you gave a roof to a vervolgde, they could also take you away or burn down your house. After an (attempted) assassination, many more regular Dutch people would get murdered.

At the end of the oorlog (war), there were about 45,000 leden (members) of different verzetsgroepen – half a percentage of the Dutch population at the time. The amount of people that helped out, or only did small deeds of verzet is much higher of course.

Radio Oranje and other news

One way that the Nazis tried to reach their doeleinden was by censorship of the media. To resist this, many illegal channels were created to still keep people informed. One of the most famous was Radio Oranje.

On July 28, 1940, two and a half months after the Dutch capitulation, the English BBC premiered a special kwartier (quarter-hour) for Radio Oranje, a new radio program for the Dutch to speak to its population in the Netherlands. Koningin Wilhelmina opened this Dutch-speaking program, where she said the following:

Ruw geweld is niet in staat een volk zijn overtuiging te ontnemen.

(Raw violence is not able to deprive a people of its convictions.)

Nederland zal den strijd volhouden, zo lang tot voor ons een vrije en gelukkige toekomst opdaagt.

(The Netherlands will continue the fight until a free and happy future appears for us.)

Radio Oranje was uitgezonden (broadcast) every day at 9 pm Dutch time. It would present Dutch news, warnings about attacks and even serve to pass on coded messages.

Even though Wilhelmina’s flight to England was seen by some as an act of cowardice, even treason, this was a clear sign that she was on the side of Dutch verzet, against the Nazis. A lot of people listened it, but the actual effectiveness of the program is hard to measure. However, it definitely helped to steek de Nederlanders een hart onder de riem (“stick the Dutch a heart under the belt” – expression meaning to support, motivate, encourage).

Of course, the Nazis forbade to listen to Radio Oranje and even installed stoorzenders (jammers). Even owning radio receivers was forbidden at some point. But the Dutch often just hid their radio away.

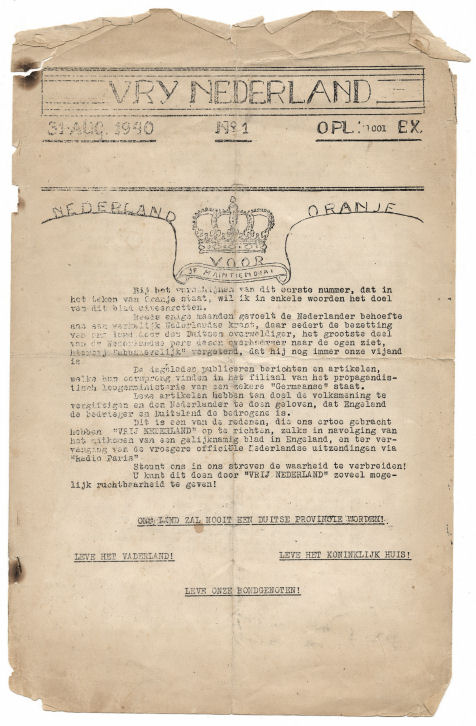

Radio Oranje was not the only way to spread Dutch news. More than 1300 illegal so-called verzetskranten (resistance newspapers) were produced by the end of the war. Kranten like Het Parool and Vrij Nederland grew very quickly, and exist to this day as national kranten. They had oplages (prints) of a few hundred to hundreds of thousands every month.

Effectiveness of verzet

How effective were all these actions? Did they really help resist the Nazi rule, save lives, and help end the oorlog? Hard to say exactly, but it is likely. The Dutch actually helped more than 350,000 people onderduiken, which is one of the highest numbers in Europe. The Nazis also never really succeeded in converting the Netherlands into a nationaal-socialistische staat. We will never know if this would have happened had the oorlog lasted longer, but the verzet definitely played an important role in resisting the Nazis.

However, not all Dutch that resisted wanted to do it from within the Netherlands. They wanted to go further and fight within an army. And those brave Dutch people we will take a look at next time.

Het verzet in modern culture

Het verzet makes for a good story, telling of the heldhaftige (heroic) and verschrikkelijke (horrible) of the oorlog. There are many Dutch movies that tell stories, some based on reality, of verzetsstrijders. Recent examples are Oorlogsgeheimen, Zwart Boek and De Tweeling.

What do you think of the Dutch verzet? Was there verzet in your country against the Nazis? Let me know in the comments below!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Gre:

Thanks so much for your blog. My mother was Dutch, a verpleeger, during the oorlog. She has been gone for a long time and anything Dutch keeps her alive in my memories.

There is a Verzets Museum in Amsterdam, It is well constructed and interesting.

Roger Green:

Ironically, whilst their own country was still a colony quite a few Indonesian students and others from what was then the Dutch East Indies were involved in the struggle for freedom against the Germans. No doubt this helped to give them added courage to return home and take up the struggle for their own “merdeka” (independence).