The End of Germany’s Coal Posted by Sten on Dec 22, 2018 in Culture, Language, Traditions

Die letzte Zeche wurde geschlossen!

In 2007, Germany decided to phase out hard coal production in 2018, which was today. Steinkohle was an important component to rebuild Germany after the Second World War. The reason is simple: Germany’s coal was simply no longer competitive on the global market.

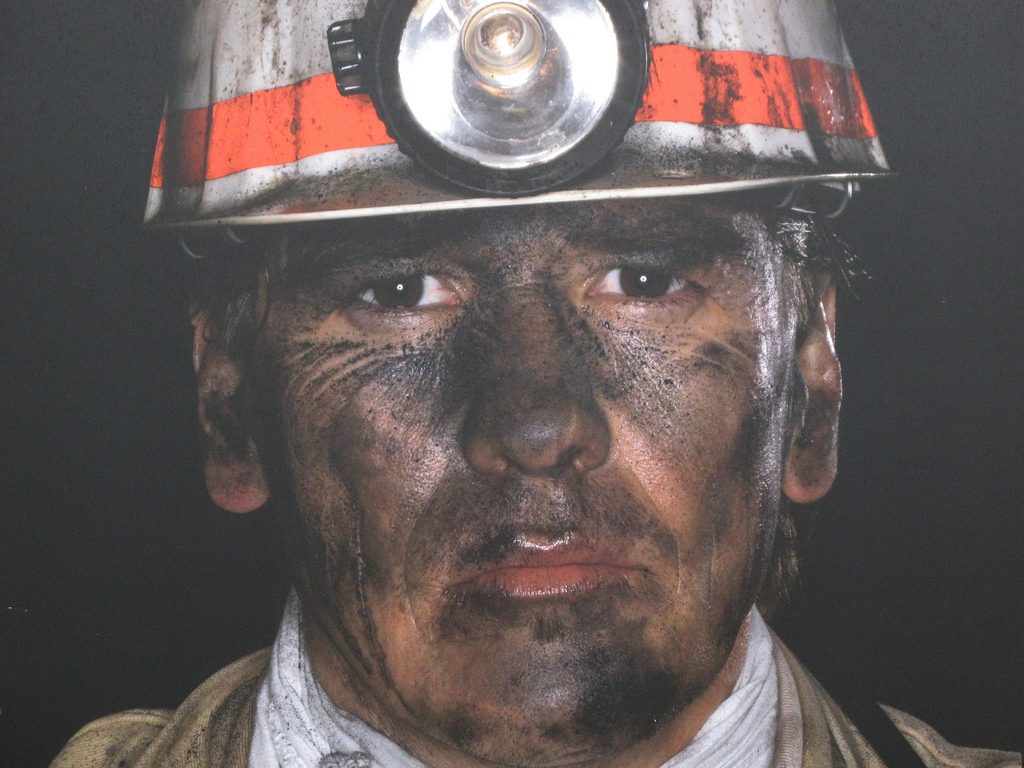

The last day of Steinkohleförderung (hard coal mining) took place at Schachtanlage (shaft mine) Prosper-Haniel in Bottrop. It was celebrated with many important Figuren (figures) of the German political world. Germany’s Bundespräsident (Federal president) Walter Steinmeier received the very last Steinkohlestück (piece of hard coal) from four miners.

Es war ein trauriger Moment (It was a sad moment).

Das war der schlimmste Tag meines Lebens (That was the worst day of my life).

Eine Epoche geht zu Ende (An epoch comes to an end).

Für uns Bergleute war es unsere Welt. (For us mineworkers, it was our world).

It was an emotional day.

However, it was unavoidable. Already in the 1970s, coal had problems. It needed Subventionen (subsidies) to stay alive, and only now, it is being phased out. Currently, the world coal price is 85 euros per ton, but it costs 170 euros to win a ton of coal in Germany. So that marked the end of German hard coal mining.

Kumpel

The term Kumpel traditionally meant “miner”, but it has become such a symbol of Verbundenheit (solidarity) and Freundschaft (friendship), because you have to be able to rely on your fellow Kumpel, that it has become a normal term. People refer to friends as their Kumpel, and that meaning has even taken over its traditional meaning! For example!

Alles klar, Kumpel? Ich hoffe, dir geht es gut!

(Everything alright, mate? I hope you’re doing good!)

Another typical term is Glück auf!, which is a simple way to wish another Kumpel good luck.

Probleme

There are, however, problems with exiting coal. Not only do the workers need new Arbeitsplätze (jobs), but also do the tunnels below lead to Absacken des Bodens (sinking of the soil) and Rissen in Gebäuden (tears in buildings). And because of the Absacken, the Grundwasser (groundwater) is closer to the surface, often comes through and leads to ponds, which need to be dammed and kept under maintenance. Furthermore, Regenwasser (rain water) flows into the tunnels and stays there, taking up the toxic substances in the mines and could mix with the Grundwasser. It therefore needs to be pumped up to the surface and be removed. And finally, the Grubengebäude (mine buildings) need to be converted, for example into Kulturhäuser (cultural centers).

This can also not be celebrated as a triumph for the environment. For one, the coal will now simply be imported from other countries. And furthermore, Germany remains one of the largest producers of Braunkohle (lignite, or brown coal). This surface-mined coal is still an important driver of energy generation in the republic, and it is not expected to be phased out for another decade or two.

If you are curious to see more about German mining and the people behind it, the German channel WDR made a short documentary last year of Andy, a Kumpel in the Ruhrgebiet. It is a 360° video, so you can look around as well as you watch!

Does your country have coal mines? How is it handled there? Let me know in the comments below!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Kelly Smith-Moore:

That would have been a sad day, indeed. My maternal grandfather, and his father, and his father before him, were coal miners in western Pennsylvania (USA) where I grew up, as was my paternal grandfather. Difficult and dangerous work…my father remembered the day when mine officials came to their school for the children whose father’s had been killed in a mining accident that day.

Poppy, my dad’s dad and who I remember well, took care of the mules in the mine. Grandpa Buck, my mom’s dad who died when I was tiny little, was too tall and broad (muscle, not fat!) to go into the mines, so he worked the coal tipple.

This was bituminous coal, or soft coal, that was mined in my little town and many of the surrounding towns that grew up around the mines in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. The hard coal, or anthracite, is more in the eastern part of the state.

My husband and I had never heard of brown coal. How interesting!

I enjoy your posts very much, and this one in particular.

James Bauernschmidt:

What new industries can be developed in order to keep people employed?