Shivrani Devi Premchand: A Shadow on The Stage Posted by Rachael on Mar 14, 2018 in Hindi Language, Uncategorized

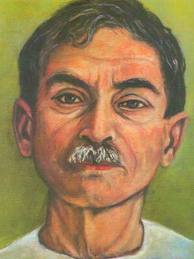

Most people familiar with Hindi literature (साहित्य/saahitya, masc. noun) readily recall the literary (साहित्यिक/saahityik) giant Munshi Premchand (or, Dhanpat Rai Shrivastav); yet, despite her contributions to Hindi literature and the Indian Independence movement, his wife Shivrani Devi, is much less renowned. Similarly, one of Premchand’s sons, Amrit Rai, composed a monumental biography (जीवनी/jeevani, fem. noun, or जीवन-चरित/jeevan charit, masc. noun) about his father, entitled कलम का सिपाही/Kalam ka Sipahi (A Soldier of the Pen), that is much more well-known than his mother’s memoir (संस्मरण/samsmaran, masc. noun) of her husband, प्रेमचंद घर में/Premchand Ghar Me (Premchand at Home). Despite her lack of fame, Shivrani Devi’s life and personality (व्यक्तित्व/vyaktitva, masc. noun) deserve to be known as an incredible woman in her own right and the driving force behind her husband’s creativity and prolificacy.

In Shivrani Devi’s memoir of her husband, Munshi (मुंशी is a respectful title for an educated man) Premchand, she introduces us to herself in the eighth chapter (अध्याय/adhyaay, masc. noun), which is titled simply “Shivrani.” As part of this introduction, she states her father’s name, Munshi Deviprasad, and the specific location of her natal home in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh): the village of Salimpur (सलीमपुर) in the district of Fatehpur (फ़तेहपुर). Her father, a relatively prosperous zamindar/ज़मींदार (landlord), married her off at the age of 11; through her description of the event, it seems less than momentous for the young Shivrani as she does not remember when it occurred or even when she was widowed. In fact, she remembers only that the marriage (शादी/shaadi, fem. noun, or विवाह/vivaah, masc. noun) lasted 3-4 months before her husband passed away. Shivrani seems to have had an especially close and loving relationship (संबंध/sambandh, masc. noun or रिश्ता/rishtaa, masc. noun) with her father. Through this bond and her father’s natural desire to see her happy, she was able to escape the misery of perpetual widowhood (विधवापन/vidhvaapan, masc. noun), which so many other Hindu widows at this time had to endure, as her father set about arranging a second marriage for her.

According to scholar Jyoti Atwal, Shivrani’s father arranged her second marriage by writing and publishing a book in 1905 called Kayastha Bal Vidhva Uddharak Pustika (A Book for the Deliverance of Kayastha Child Widows) in which he included an advertisement (विज्ञापन/vigyaapan, masc. noun) for the remarriage of his daughter. Interestingly, in this chapter about Shivrani, she does not mention the book her father wrote, only the advertisement. Fortunately, Premchand saw this advertisement and wrote to Shivrani’s father, stating his desire to marry as well as his educational qualifications and salary (वेतन/vetan, masc. noun). The two men arranged to meet in Fatehpur and, as Shivrani’s account goes, Premchand made a favorable impression on her father. Scholar P. Lal is perhaps too quick to idealize Premchand when he reports that “in marrying Shivrani, Premchand made it a condition that there was to be no dowry (दहेज/dahej, masc. noun), though, as an eligible bachelor he could have easily claimed it”; this is, in fact, not the case according to Shivrani’s account, in which she states that, at the conclusion of their meeting, her father gave Premchand money for rent and a barccha (or बरच्छा/बरेच्छा), which is a settlement for all or part of a bride’s dowry. It seems that the young Shivrani did not have much say in this second marriage either, because she writes, “I wasn’t even aware of where my wedding was taking place” (“मुझे यह भी नहीं मालूम कि मेरी शादी कहाँ हो रही है”) (PGM 29).

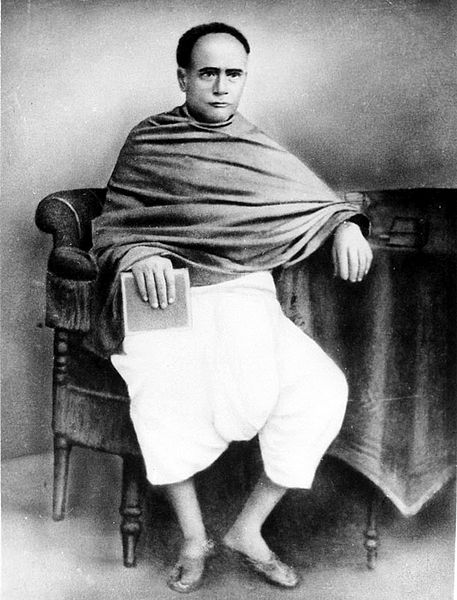

Although the Bengali Renaissance figure Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar had campaigned for the remarriage of Hindu widows to be legalized in the 1850s, the effects of his campaign (आंदोलन/aandolan, masc. noun) and the colonists’ subsequent legalization of widow remarriage in 1856 were uncertain on the ground. For example, in the 1880s, sending widows to a home reserved for such women was considered more practical and desirable in the popular imagination. However, Atwal states that “with the popularization of print culture in the early 20th century, the idea of widow remarriage was rejuvenated. This rejuvenation was [in part] motivated by…newspaper reporting on the killing of illegitimate infants by widows. [Additionally the] representation…of widows as perpetual sufferers also evoked powerful emotional responses among readers.” It was in this more sympathetic climate that Shivrani obtained a second chance (मौका/maukaa, masc. noun) at marriage and fulfilling the duties of a female householder, which are enshrined in some Hindu scriptures as the most important aspects of a woman’s life. Shivrani’s high caste (Kayasth/कायस्थ, a scribe caste generally regarded as Kshatriyas/क्षत्रिय or one of the three twice-born castes) undoubtedly increased her chances of remarriage as caste (जाति/jaati, fem. noun) was often a critical object of consideration in determining for whom it would be more acceptable to remarry.

Shivrani speaks of Premchand’s decision to marry her, a child widow (बाल-विधवा/baal-vidhvaa), with evident pride when she states that, “your aunt’s [actually Premchand’s stepmother] opinion, etc., was not consulted in our marriage. But this was your audacity. You wanted to break off your ties to society to the point that you didn’t even give the news to your relatives” (“मेरी शादी में आपकी चाची वग़ैरह किसी की राय नहीं थी । मगर यह आपकी दिलेरी थी । आप समाज का बंधन तोड़ना चाहते थे । यहाँ तक कि आपने अपने घरवालों को भी ख़बर नहीं दी”) (PGM 29). This was indeed a bold and unusual move on Premchand’s part, most likely influenced by Premchand’s own reformist social beliefs (धारणा/dhaaranaa, masc. noun) and the fact that his father had married him off previously when he was only a teenager (किशोर/kishor, masc. noun); in fact, he was still married at the time of his marriage to Shivrani, which she did not discover until later.

Despite Shivrani’s remembrance of Premchand’s actions, which is clearly tinged with pride (गर्व/garv, masc. noun) and affection (स्नेह/sneh, masc. noun), immediately after her marriage, she was generally unwell as her mother had died when she was fourteen (she was married at 16). Moreover, in making the painful transition from her natal (मायका/maaykaa, masc. noun) to marital home (ससुराल/sasuraal, fem. noun), Shivrani missed her brother dearly, who was 11 years her junior and whom Shivrani loved and cared for as if he were her own son. After her mother’s death, Shivrani makes the telling statement that she essentially became the woman of the house: “From that time [of my mother’s death], I became aware of my responsibilities” (“उसी समय मुझे अपनी जिम्मेदारियों का ज्ञान हुआ”) (PGM 29).

Inspired by her husband and her own desire to challenge herself in the arenas of reading and composition, Shivrani’s literary work was published for the first time in 1924 in the form of a story, “साहस/Sahas” (“Courage”); this story appeared in a well-known women’s journal of the time, called “चाँद/Chand” (“Moon”). Later, Shivrani would go on to write a full-length memoir of her famous husband, which would be published in 1944 in the midst of the Progressive Writer’s Movement, which began in Lucknow in 1936. During this movement, “literary intellectuals revisited and reworked their political associations and ideological commitments,” often bringing controversial social issues to the fore of their writing (Atwal). This movement and the ideologies it espoused may have influenced Shivrani to boldly state her progressive stance on certain social issues primarily affecting women and craft a memoir about her famous literary husband with such a strong imprint of her own personality and experiences (अनुभव/anubhav, masc. noun) (Atwal). This was an especially fruitful time for those with strong social (सामाजिक/saamaajik) views, as the literary movement that came before, known as “Chhayavad” or “Neo-Romanticism” did not generally delve into contemporary social and political issues, but rather focused on abstract discussions of universal human emotions (भावना/bhaavnaa, fem. noun) and experiences. Despite these and other contributions to the Hindi literary sphere, Shivrani’s Premchand Ghar Me is not often addressed in scholarship on Premchand and, if it is, it is given only passing attention.

Not only was Shivrani Devi a writer (लेखिका/lekhikaa, only for a female writer, लेखक/lekhak for a male writer) and enthusiastic participant (सहभागी/sehbhaagi) in the Hindi literary sphere, she was also an activist and was sent to jail multiple times for supporting the Indian Independence movement. Considerate of her husband’s chronic ill health, she often went to jail in his stead, allowing him to bolster the movement with his writings. She was also a hardworking and dedicated mother and housewife and, for these many reasons, deserves her place amongst the literary giants of the modern age (आधुनिक ज़माना/aadhunik zamaanaa).

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.