The wisdom of the vikings – Hávamál Posted by hulda on Apr 16, 2013 in Icelandic culture, Icelandic history

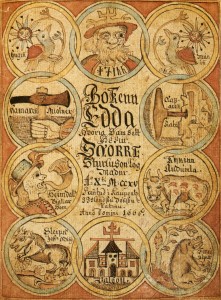

What was life like in the Medieval times? How did people view the world they lived in, how did they value it and what were their moral codes? When it comes to Iceland we know much more than for most of the now known world because so many Icelandic texts have survived all through the years! Iceland can boast for having the largest collection of medieval literature written in Old Norse, some thousands of texts. One of the most popular is called Hávamál, the speech of the high one (= Óðinn) and it’s found in the Poetic Edda.

Hávamál can be divided into sections based on their content, of which the first one called Gestaþáttr includes guidance in poetic form for living a successful and happy life. It is still often quoted, and no wonder since the advice within has not been affected by the hundreds of years that have passed since it was penned down.

A virtuous person, Hávamál stresses, is one who is moderate in everything. A happy one is never too much of this or that because extremes bring about them much unhappiness, and at times the stanzas in it seem to carry a double meaning, so it’s best to meditate on each one of the little poems rather than just take them at face value. Much importance lies in how something is said – which happens to be one of the key advice Hávamál offers as well!

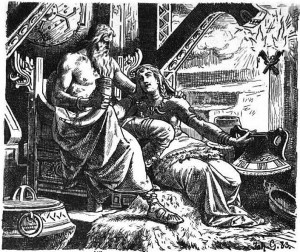

Óðinn disguised as a traveler. I just keep seeing Tolkien’s Gandalf though…

Poems 1-11: advice for someone who’s travelling and does not know whether they’re among friends or foes. In Medieval times this could have been a matter of life and death, but the advice can be applied to the present day as well even if we’re no longer risking an ax to the head.

6.

Að hyggjandi sinni

skylit maður hræsinn vera

heldur gætinn að geði.

Þá er horskur og þögull

kemur heimsgarða til

sjaldan verður víti vörum

því að óbrigðra vin

fær maður aldregi

en manvit mikið.

“Of one’s own knowledge/shouldn’t a man shout about/rather keep his thoughts to himself. /When a wise and quiet one/comes to a new village/he makes few mistakes/for more trustful friend/a man shall never have/than his own wit.”

Silence is golden. Boasting about one’s own skills/knowledge/opinions to people one doesn’t know is rarely a good idea. What’s more, there’s a chance to goof up so badly that it will bring about enemies with sharp blades – just read any old Icelandic saga to find an example of what happens next.

The parts 12-14 address drinking. It’s important to note, though, that the advice is not to avoid drinking but to do it in moderation, and using himself as an example Óðinn tells how he once drank himself under the table at the giantess Gunnlöð’s place, losing most of his memory of the night, and how the best parties in his opinion are the ones you can remember afterwards.

From part 15 to 18 the text warns against being cowardly or making a fool out of one’s self.

16.

Ósnjallur maður

hyggst munu ey lifa

ef hann við víg varast.

En elli gefur

honum engi frið

þótt honum geirar gefi.

“A stupid man/thinks he might life forever/if he in battle falls back. /But old age gives/him no peace/although spears gave it.”

In confrontation one should stand one’s ground. Trying to save one’s self will only result in bad reputation.

In our time this could mean for example that if you end up in an open confrontation you should stand behind your own words. Don’t try to make excuses for your deeds but face them: apologize where you’ve done wrong instead of trying to explain yourself away. Accept the possible outcome that you may be proven wrong – it will hurt your pride but such “battle wounds” will heal well and leave no lingering regrets in the back of your mind.

Stanzas from 19-23 stress the importance of moderation and power over one’s self. The Medieval Icelanders viewed self control so important that it’s the basis of the whole Gestaþáttr. The reader is advised to hold their tongue, to listen rather than to speak, avoid picking fights and to drink, eat and worry only in moderation. While the others are easily understandable that last part may sound weird. How can one worry in moderation?

The way this was seen in the Viking era was that worrying in itself was not a bad thing because it was vital to be ready to face difficulties. However, worrying endlessly over problems that could not be solved was seen as self indulgence and therefore bad. As Hávamál puts it:

23.

Ósvinnur maður

vakir um allar nætur

og hyggur að hvívetna.

Þá er móður

er að morgni kemur,

allt er víl sem var.

“Stupid man/stays awake all night/and worries about everything. /Then is tired/when the morning comes/everything is as it was before.”

This should not be taken as some kind of jab at people who actually have anxiety or are suffering from depression. I would rather think of it as a general warning against negative thought processes that we all have. Did you make some embarrassing mistake while trying to speak Icelandic to an Icelander? Forgive yourself the mistake, don’t fret over it endlessly or you’ll risk jeopardizing your own learning process if you become too shy to use the language. Most likely you’re the only person that even remembers that mistake anyway.

From 24 to 32 Gestaþáttur considers when one should talk and how, and when being quiet might be the better option. Yet, like mentioned before, these stanzas can actually address the matter deeper than the first look would have it.

28

Fróður sá þykist

er fregna kann

og segja ið sama.

Eyvitu leyna

megu ýta synir

því er gengur um guma.

“Wise seems that man/who knows how to ask/and how to answer. /No secret/can stay among men/of the things that happen between them.”

The one who asks the right questions and answers truthfully, but carefully, will seem like a wise person. Trying to keep secrets that will come out sooner or later anyway is unwise. In short, this poem tells you to be honest and sincere about the things that have been done, but also to watch how you speak and of what.

Perhaps you had a disagreement with someone and have to explain yourself to a third person. If you yourself did or said things that added up to the fight it’s best to come clean about them in as non-aggravating manner as possible. There’s a huge difference between saying “Yes, I called her a XXXXX because she really is one!” and “Yes, I called her a XXXXX and I wish I hadn’t, it was horrible of me.”

Does it matter whether you actually are feeling sorry about the name calling? Gestaþáttr says – no! In poems 33-35 and 41-46 it’s often stressed that you should be courteous even to the people you don’t trust, and that your outcome will almost certainly be better with friendliness than aggression.

36-40 and 47-49 are general advice of self sufficiency and the handling of one’s properties. Owning even a little is a blessing and outward appearances can deceive: no man is worse for not being rich.

The importance of friendship appears in 50-52. Here is where a very popular saying comes from: Maður er manns gaman. It’s a bit tricky to translate but the general gist of it is that no man is an island; a human finds happiness in another human’s company.

Poems 53-60 are my own personal favourite – they suggest moderation is equally important in braininess! Or perhaps, rather, that common sense is worth much more than endless wisdom, for it’s common sense that’ll keep you alive and able to not worry beyond that which is necessary.

56.

Meðalsnotur

skyli manna hver,

æva til snotur sé.

Því að snoturs manns hjarta

verður sjaldan glatt

ef sá er alsnotur er á.

“Middle-wise/should every man be/and never too wise. /For a wise man’s heart/becomes rarely happy/if he is too wise.”

Too much knowledge can cause much unhappiness.

61-77 deal with a variety of subjects such as reputation and necessity: what one really needs and how much of it. There’s also a strong message of the importance of being alive and how no one is useless, no matter how “faulty” they may seem:

71.

Haltur ríður hrossi,

hjörð rekur handar vanur,

daufur vegur og dugir.

Blindur er betri

en brenndur sé,

nýtur manngi nás.

“The lame can ride a horse,/a flock of cattle can be driven by a handless,/the deaf can fight a battle bravely. /It’s better to be blind/than to be burned/the dead are no use to anyone.”

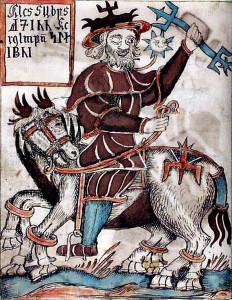

Don’t judge a book by its cover. There’s a talent within everyone, so don’t scorn a person based on appearances. You can trust Óðinn’s word on this, after all he’s only got one eye and that’s never stopped him from being the king of æsir. 😉

Here are a couple of proverbs read out – some that are in this entry and others that aren’t, but which nevertheless give an interesting look into the moral code of the Medieval era.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!

Comments:

Kris Olafson:

I missed that you had posted this until today! Absolutely fabulous!

Thanks for your perspective! Very helpful as well as enlightening!

hulda:

@Kris Olafson I have a soft spot for Óðinn’s lessons: once we got to translating them and their real meanings in class I’ve never turned back. There’s something about balance and temperance that really resonates with me.