The Beach: Irish Terms from “Swash” to “Berm” Posted by róislín on Jul 20, 2019 in Irish Language

(le Róislín)

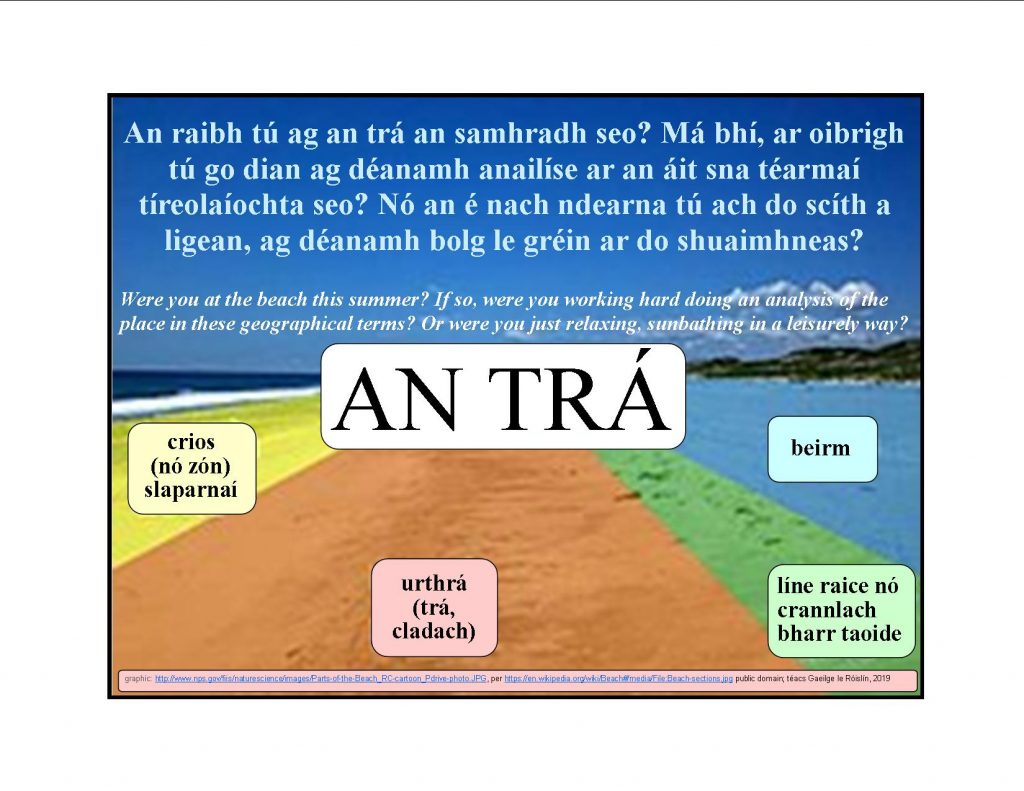

It may seem like a simple thing to just say you’re going to the beach (or “the strand” or “the shore”), but in reality, there are many zones or parts to a beach. They have interesting names in English and so, there’s also a slew of interesting Irish vocabulary words to match. Here are a few:

1)) Closest to the water, the swash zone: “slaparnach” is the Irish for “swash” and it may be clarified by “na dtonn” (of the waves).

After a word like “crios” (belt, zone) or “zón,” the word “slaparnach” changes to “slaparnaí,” since we’re now saying, “zone _of_ swash.” Irish doesn’t use a word like “of” in this case — it just changes the end of the final word.

2)) Next, the main and probably widest area: urthrá (to really specify “foreshore” as opposed to “backshore”). For pronunciation, remember the “t” of “trá” is now silent, so it’s approximately “ur-hraw.” We could also simply say “trá” (beach, strand, shore) or “cladach” (beach, strand, shore, sometimes specifically a “rocky foreshore,” although a rocky beach can also be a “duirling” — there’s never a shortage of vocabulary in Irish, especially where nature is concerned).

3)) Third, we have the “wrack line,” where most debris from the sea (like “raic” or English “wrack” is deposited and may remain until there’s a really high tide). In the graphic above, we don’t see any actual wrack, just the green area, but typically there would be seaweed (feamainn) and driftwood (adhmad farraige). Sadly, these days, there might also be “bruscar” (litter) or other debris (“smionagar” or “treascarnach“).

Another way to say “wrack line” is “crannlach bharr taoide,” a really interesting phrase. “Crannlach” does derive from “crann” (a tree), although we might wonder why, since trees don’t typically grow right in the middle of a sandy beach. But with the suffix “-lach,” the word now means “brushwood,” “withered stalks,” or “haulm” (another intriguing English word, meaning “stems” or “stalks” in general, especially after a crop has been harvested). Adding “b(h)arr taoide” specifies that this is high (barr) tide (taoide) brushwood (as it were), in other words, this is specifically a maritime feature, not agricultural.

4)) Finally, we have the “berm,” which is almost the same in Irish: beirm (an bheirm, the berm, na beirmeacha, the berms). This is the raised strip of land separating the beach area from the non-beach inland terrain. Clearly, this word is closely akin to the English and is probably a recent borrowing. Interestingly, Irish also has two other terms that could be used for “berm” (berm terms!) but my hunch is that these are not used as much nowadays, since “beirm” is so easily recognizable. The additional words are cosán dreapa (from “cosán,” a walking path or trail, and “dreapa,” related to “dreap,” climb), and laftán (ledge, overlook, shelf, stand).

So, whether you go to the beach just to relax (do scíth a ligean) or to learn more about the environment and the relevant Irish vocabulary, now you have a little more specific background for defining the territory. And if you lose your “lionsaí tadhaill” (contact lenses) at the beach, now you can tell your friends where to help you look: sa chrios slaparnaí, san urthrá, sa líne raice, or sa bheirm, srl. And good luck (ádh mór) with that. Slán go fóill — Róislín

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: