Three ways to spell ‘August’ in Irish: historic, dated, and modern (Lúnasa et al.) Posted by róislín on Jul 31, 2018 in Irish Language

(le Róislín)

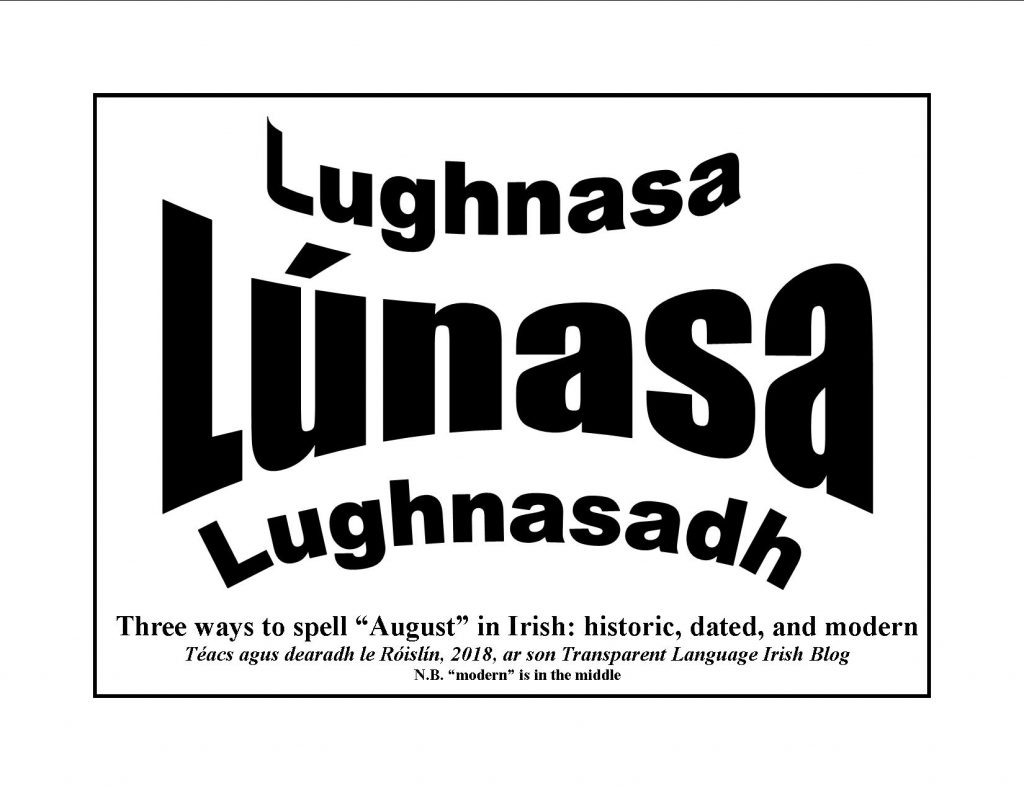

As you can see from the graphic above, there are three different ways to spell “August” in Irish:

the modern way: Lúnasa

a dated way, mostly found before 1960-ish: Lughnasa

a historic way, going back to the Middle Ages: Lughnasadh. Even that is somewhat of an adaptation, as it originally would have been: Lugnasad. The “g” and the “d” were probably initially pronounced but, over time, became silent or softened. Eventually dots were added over the “g” and the “d” (Luġnasaḋ), and even more recently (1950s), the letter “h” was used to substitute for the dots. Adding the h’s made this word, and thousands of others, look even longer than their older spelling. But another compromise was made during the spelling reform of the 1950s. Some of the silent letters were removed, and in some cases, the vowel was marked long instead. That’s why the modern spelling has a long “ú” (or “ú-fada”). The long mark (the “síneadh fada”) indicates that the “gh” was silent and has been removed.

In addition to talking about “Lúnasa” in general, we can also say “Lá Lúnasa,” which is specifically August 1st, and “Mí Lúnasa,” the month of August.

“Lá Lúnasa” was a harvest festival, in recent centuries welcoming in the new potatoes, following the “Hungry Month” of July, when the previous season’s supply of “prátaí” (or “fataí” or “préataí”) might be growing scarce. In earlier centuries, prior to the introduction of potatoes to Ireland (about 400 years ago), it would have been other crops. One of the traditional activities for Lúnasa was dancing around bonfires on the hillsides, probably a descendant of some pre-Christian ritual honoring the Celtic god “Lugh.” Another traditional activity for Lá Lúnasa was gathering fraocháin (bilberries aka whortleberries or blaeberries, that’s “blae-“, not “blue-“, although the fruit is similar; the Latin taxonomic name is Vaccinium myrtillus).

Speaking of blueberries, and a scrumptious topic at that, Irish distinguishes the American blueberry from the bilberry with the following term: an fraochán gorm Meiriceánach (Vaccinium corymbosum), which in and of itself has at least seven names in English (the blue, tall, or swamp huckleberry, and the highbush, northern highbush, high, or swamp blueberry). And in case you weren’t aware, there is also a lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), which in Irish is called “fraochán caolduilleach,” lit. “narrow-leaved bilberry.” Interesting that the Irish is much more like the Latin (angustifolium) than like the English, which describes the nature of the plant as a whole.

Outside Gaeltacht and the cibear-Ghaeltacht, August 1st is probably most recognized through Brian Friel’s Tony-award-winning play, Dancing at Lughnasa, also made into a movie with Meryl Streep. Friel probably picked up much of his Irish in the 1930s and 40s, prior to the spelling reform, so his title reflects the spelling of the day. The play is set in 1936, so we could also say that he used the spelling that his characters would have known..

Whether Friel really weighed the question, “Should I spell this as “Lughnasa” or “Lúnasa” for an English-medium work of literature?” will probably remain unanswered. But, as a language teacher, the spelling issue jumps out at me. Friel’s play was first produced in 1990, by which time the spelling reform was well entrenched, even if not everyone is satisfied with it. Today, you won’t even find “Lughnasa” as such in many modern Irish dictionaries, only “Lúnasa.” So using the older spelling definitely was making a statement, either reflecting Friel’s student days, harkening back to the god Lugh, or being deliberately a bit old-fashioned.

At any rate, now we’ve seen all three versions of how to spell “August” in Irish. It just depends what decade or century is involved. For most modern purposes, I recommend “Lúnasa.” If you’re discussing Friel’s play, of course, use his spelling to refer to the title. Meanwhile, maybe this is a good time for making muifíní or pióga or pancóga with whichever of the berries you prefer.

Pronunciation note: from the modern perspective, Lúnasa, Lughnasa, and Lughnasadh are all pronounced the same [LOO-nuss-uh]. The stress is on the first syllable. The “gh” and “dh” are effectively silent, as is the case with many words previously discussed in this blog series, like “foghlaim,” “rogha,” “foghlaí mara,” “síneadh,” and “fadhb.”

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Kevin Traynor:

Interesting about the the now silent letters in Irish originally being sounded. I’ve been puzzled for years about that, as many of the ancient Irish words are often written without the aspiration in books about ancient Irish history. Thank you.

róislín:

@Kevin Traynor Glad you found it suimiúil (interesting)!