More False Friends Posted by Geoff on Dec 7, 2015 in Uncategorized

Following on from last week’s article Italian False Friends, and taking into account the contributions made by you in your comments, we’re going to take a look at a few more common false cognitives.

Common False Friends:

argomento can be mistaken for ‘argument’ but actually means ‘topic’, e.g. stamattina il maestro ci ha introdotto un argomento molto interessante … il sesso! (this morning the teacher introduced us to a very interesting topic … sex!)

assistere can be mistaken for ‘to assist’ but usually means ‘to attend’ or ‘to be present at’ e.g. ieri abbiamo assistito ad un bello spettacolo al teatro (yesterday we attended a great show at the theatre). In some cases it also means ‘to assist/help’ e.g. assistere un povero (to help a poor person), assistere un malato (to assist an ill person)

comprensivo can be mistaken for ‘comprehensive’ but actually means ‘understanding’, e.g. Marco è un ragazzo molto comprensivo (Marco is a very understanding guy)

confrontare can be mistaken for ‘to confront’ but actually means ‘to compare’, e.g. devo confrontare queste due stampanti per capire qual è la migliore (I need to compare these two printers in order to understand which is better)

educato can be mistaken for ‘educated’ but actually means ‘polite/well mannered’, e.g. Federico è stato molto educato (Federico was very polite). Hence maleducato means ‘rude/impolite/badly mannered’, però sua sorella è stata un po’ maleducata (however, his sister was a bit rude)

fabbrica can be mistaken for ‘fabric’ but actually means ‘factory’, e.g. ho lavorato nella stessa fabbrica per quindici anni (I’ve worked at the same factory for fifteen years)

fattoria can be mistaken for ‘factory’ but actually means ‘farm’, da ragazzo mi piaceva andare alla fattoria del babbo del mio amico Carlo (when I was a lad I used to like going to my friend Carlo’s father’s farm)

intendere can be mistaken for ‘to intend’ but actually means ‘to understand’, e.g. mi hai inteso? (did you understand me?), tu non intendi nulla di questo argomento, vero? (you don’t understand anything about this topic, do you?)

libreria can be mistaken for ‘library’ but actually means ‘bookshop’, see: In a Bookshop in Italy

morbido can be mistaken for ‘morbid’ but actually means ‘soft’, e.g questa è una stoffa molto morbida (this is a really soft cloth)

parente can be mistaken for ‘parent’ but actually means ‘relative’, e.g. questo week-end vengono i miei parenti da Genova (my relatives from Genoa are coming this weekend)

rumore can be mistaken for ‘rumour’ but actually means ‘noise’, e.g. cos’è quello strano rumore che sento? (what’s that strange noise that I can hear?)

simpatico can be mistaken for ‘sympathetic’ but actually means ‘nice/friendly/likeable’, e.g. Pontremoli è una città simpatica (Pontremoli is a friendly town), Lucia è una ragazza molto simpatica (Lucia is a really likeable girl)

False False Friends?

Some words are simply considered false friends based on a misunderstanding of their etymology. These words can be our friends because we can actually learn a lot from them if we look a bit deeper.

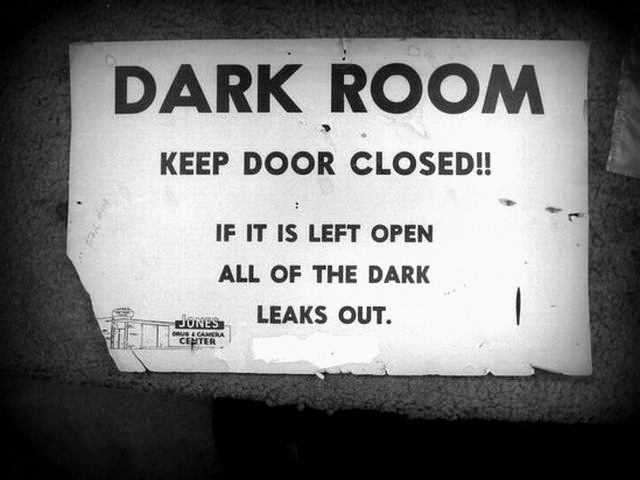

Take the word camera for example: the original name for the device that we use to take photos was camera obscura (Latin: dark room). In contemporary English, we’ve dropped the word ‘obscura’ and shortened the name to ‘camera’. So, in actuality, camera still means room whether we’re referring to a photographic machine or speaking about a room in Italian, it’s just that we’ve forgotten it. In fact, the Italian name, macchina fotografica, is probably more accurate and contemporary.

Thanks for your helpful comments, keep them coming!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Jack:

I greatly enjoy your frequent emails. They are a great help to me, However….

I am an American, living in Italy

I have difficulty in learing Italian for several reasons, One, There are numerous stranieri who speak English, so the conversation naturally drifts to that language, Another, My Italian girlfriend is an English teacher in the Italian School System, She wont teach me Italianbut prefers to improve her English with me. I try to learn, but I have few opportunities to speak and my Italian grammar is poor. Lastly most ofmy Italian friends want to learn English rather than encourage me to speak Italian.

Geoff:

@Jack Salve Jack, dov’è che abiti in Italia? Secondo me, devi trovare più situazioni che ti costringono a parlare solo l’italiano. Dove abito io c’è poca gente che parla l’inglese, ma capisco che se magari abiti in una città più grande ci saranno più persone che avranno voglia di praticare l’inglese con te. E’ difficile lo so, mi bisogna insistere … devi dire: “oggi parlo solo l’italiano, punto e basta!”

A presto, Geoff

Michael Stevens:

Love, love, love these posts. Each one is informative and lots of fun.

Chippy:

Molto interessante riguardo a ‘Camera obscura’. Grazie per tutte le parole.

Ginny:

I really this blog, especially today’s because I could actually understand all of the Italian words! And I especially like to read about about your cats! Just wish there was a device to HEAR the Italian being spoken after we read it as it is so much easier to read than, for me, to understand when someone is speaking.

But, thank you so much for your interesting ruminations and teachings.

Rick:

Questo fa senso, grazie per l’informazione

Geoff:

@Rick Salve Rick, ti volevo solo far notare che l’espressione ‘fa senso’, in inglese, vuol dire ‘gives one the creeps’, or ‘revolts’. Ad es. “gli ragni mi fanno senso” (spiders give me the creeps).

In Italian the English expression ‘to make sense’ translates as ‘avere senso’. E.g. “questa lezione ha senso” (this lesson makes sense).

A presto, Geoff

paolo minotto:

Buono post! Grazie tanto!

Martin D:

It might be in the thread but I still wonder WHY is morbido so far removed from its Latin origin.

Sorry if I am missing something obvious

Serena:

@Martin D Salve Martin, no, the passage from the original negative meaning of morbido to the modern positive one is not so obvious.

The adjective morbido (soft) comes from the Latin noun morbus = illness, disease. It originally described the sensation of yielding, of giving way under pressure, typical of an ill body, which has lost muscular tone. From here, morbido has lost its negative feeling to become a positive adjective.

The negative meaning is still found in the noun morbo (illness) and the adjective morboso (morbid, pathological).

Saluti da Serena