The Tree of Life – Part 1 Posted by Geoff on Jan 21, 2015 in Culture

Castagno = Sweet Chestnut Tree

Castagna (plural castagne) = Sweet Chestnut/s

Castagneto = Chestnut Plantation

Up until just a few decades ago, the humble castagna was a vital part of the Italian contadino’s (peasant’s) diet. Il castagno, often referred to in times past as l’albero del pane (the bread tree) proliferated around small towns and villages during medieval times, where it was carefully cultivated in order to provide a plentiful supply of its highly nutritious fruit.

Here in Lunigiana, northern Tuscany, it’s easy to find remnants of this important culture. A walk amongst the wooded slopes of the Appennino Toscano Emiliano mountains, which seen from a distance appear untouched by the hand of man, will reveal ancient terraces supported by dry stone walls upon which repose stately gnarled examples of the once precious trees. These terraces, carved into the slopes with the most basic of tools and a huge amount of effort, served to collect the castagne when they fell from the trees in the autumn, thus rendering them easier to gather.

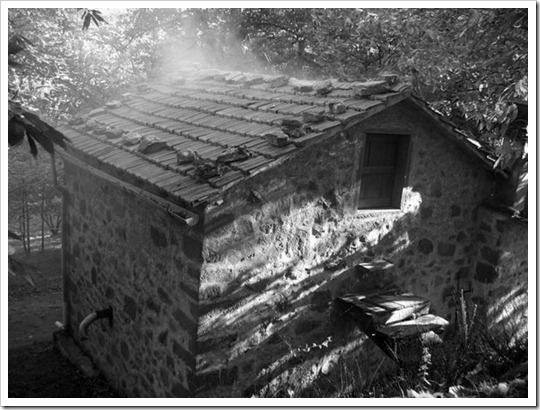

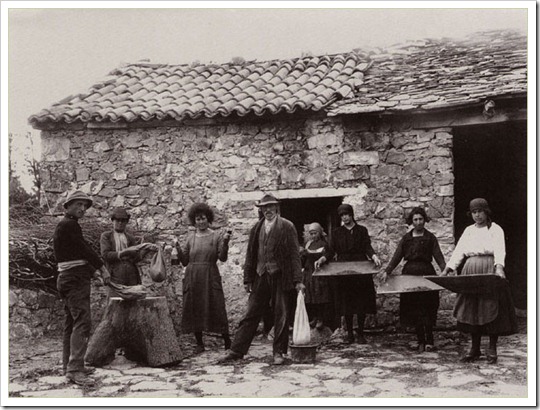

Another very evident trace of the ‘chestnut culture’ is the ubiquitous metato (chestnut drying barn) or seccatoio (literally: dryer) which in our part of Lunigiana is commonly known as il gradile. In fact we have a gradile on our land, which has now been transformed into a small but useful dependance, or guest apartment. But when we bought our property a decade ago the gradile was still as it had been left by the previous owners, blacked by years of fuliggine (soot) from the fire which was used to essiccare (dry) the castagne, and imbued with a mouth watering odour of roasted chestnut.

The primitive and labour intensive task of drying le castagne is well documented in a fascinating article which I recently found in the monthly news sheet, TuttoMontagna. Here are some edited extracts from the article together with my translation into English:

Il metato … era composto da un unico locale all’interno del quale il piano terra era diviso dal primo piano non da un soffitto ma da una serie di travetti di legno, che andavano naturalmente da una parte all’altra della stanza, a un metro circa di distanza l’uno dall’altro. La preparazione del metato consisteva nel chiudere lo spazio vuoto esistente fra i travetti, appoggiandovi sopra, nell’altro senso, i canìcce (listelli di legno triangolari di 3 o 4 centimetri di spessore), che venivano disposti così vicini l’uno all’altro da impedire che le castagne potessero cadere nella fessura che si veniva a creare tra di loro. La forma triangolare faceva sì che le castagne, incastrandosi fra l’uno e l’altro, li bloccassero con il loro peso.

The metato … was composed of a single building, inside of which the ground floor was divided form the first floor, not by a ceiling, but by a series of wooden beams set about 1 meter apart which ran, naturally, from one side of the room to the other. The preparation of the metato consisted of closing the spaces between the beams by resting i canìcce (triangular laths of wood around 3 to 4 centimetres thick) crosswise upon them. These (canìcce) were placed close to each other in order to prevent the chestnuts from falling through the gaps that were created between them. Their triangular form ensured that the chestnuts, slotting between the laths, blocked the gaps with their weight.

Nel metato, il fuoco veniva acceso a piano terra e il calore, insieme al fumo, filtrava attraverso i canìcce facendo essiccare le castagne. Il fuoco, però, doveva consumarsi lentamente, senza che la fiamma divampasse, altrimenti le castagne avrebbero assunto un colore rossastro e anche il sapore ne avrebbe probabilmente risentito. Il legno utilizzato per questa delicata operazione era, naturalmente, castagno, ma più dei rami erano adatte le radici, e per questo motivo durante l’anno era già stata messa da parte qualche ciòca (ceppo con radici).

In the metato, the fire was lit on the ground floor and the heat, together with the smoke, filtered through the lathes and dried the chestnuts. The fire, however, had to burn slowly, without blazing, otherwise the chestnuts would become reddish in colour, and the taste would also have been affected. The wood used for this delicate operation was, naturally, chestnut, but it was the roots that were favoured over the branches, and for that reason a few bundles of roots would have already been put apart during the year.

Una funzione importante, in questa fase, la svolgeva la pùla, che veniva conservata da un anno all’altro. Ricoprendo infatti il fuoco con questa specie di segatura si impediva che le fiamme divampassero, mantenendo il calore e permettendo alla legna di durare più a lungo.

During this phase the pùla (the dried chestnut husks), which was set aside from one year to another, played an important role. In fact covering the fire with this sawdust like material prevented the fire from blazing up, thus maintaining the heat and allowing the wood to last longer.

La canìciâda, cioè la fase di essiccazione, durava in media 45 giorni, ma a metà circa di questo periodo era necessario “voltare” le castagne e questa era sicuramente l’operazione più delicata dell’intera lavorazione. Per “voltare” le castagne, cioè spostare quelle che durante i primi venti giorni erano più vicine al fuoco, sostituendole con quelle che invece si trovavano sopra le altre, si usava una tavola con la quale si “raschiava” lo strato di castagne, asportandone una certa quantità, che poi veniva messa da parte dentro un sacco. Questa operazione veniva ripetuta fino a quando tutte le castagne erano state raccolte, quindi, partendo dal primo che era stato riempito, si tornavano a vuotare tutti i sacchi sopra ai canìcce.

The the drying phase (La canìciâda in dialect) lasted around 45 days, but about half way through this period it was necessary to turn the chestnuts, and this was definitely the most delicate part of the whole operation. In order to turn the chestnuts, in other words move those that were closest to the fire during the drying process, and substitute them with those that were above, a board was used to ‘scrape’ the layer of chestnuts, taking away a certain amount which would be put aside in a sack. This operation was repeated until all the chestnuts had been collected, then, starting with the first sack that had been filled, they were poured once again onto the lathes.

to be continued ……..

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

paolo:

Grazie per condividere questa informazione.

Io adoro le castagne ma la stagione qui negli stati uniti è piuttosto breve. Ovviamente le castagne migliori provengono dall’italia. (Le peggiori provengono dalla Cina.)

Quali mesi sono le castagne disponibile in Italia? Dove sono le regioni migliori in Italia per ottenere le castagne?

Geoff:

@paolo Ciao Paolo, purtroppo il peggio di quasi tutto proviene dalla Cina, e ormai, qua in Europa, ne importiamo una marea tutti i giorni. È una cosa che mi da tanto fastidio!

Le castagne cominciano a cadere verso la fine di settembre. Per quanto riguarda le regioni migliori … boh! dipende dal gusto, ma quelle più famose, i marroni che si usano anche per fare marron glacé, vengono da Piemonte.

A presto, Geoff

Rita:

Si dice che una volta negli Stati Uniti c’erano molti castagneti poi e’ arrivata una specie di piaga o malattia che ha distrutto tutti I castagneti. Le castagne che si vendono durante la stagione Natalizia nel N.J. e N.Y,sono importate dall’Italia e costano un sacco di soldi e molte volte sono vecchie e fradice . E questa e’ la storia delle castagne americane.

paolo:

Interessante Rita, non l’ho sapevo.

In California, le castagne sono disponibile ma non sono facile a trovarle, di solito solo 3 mesi – la fine di novembre, dicembre e gennaio. Ce ne sono coltivate nel nord di California e Oregon, ma penso che non siano buone come le castagne italiane.

E Geoff, riguardo alle cose cinesi, ho incontrato una persona cinese che mi ha detto che lui non mangia né compra qualsiasi cibi che sono coltivati in Cina. E lui abita a Hong Kong.

Sono d’accordo con te: i Cinesi hanno creato un nuovo standard di bassa qualità nel mondo.

Rosalind:

È quì in Corsica la castagna era sempre stata il cibo di base. Dopo che i francesi avessero vinto l’isola nel 18esimo sécolo, il ré di Francia ha vietato la produzione di castagne dicendo che faceva una popolazione pigra e i corsi dovevano seminare il grano. Soltanto dopo qualche anno, i francesi si sono resi conto che il castagneta conviene meglio in montagna e la sua produzione era autorizato di nuovo.

Rosalind:

Ora purtroppo c’è il problema della malattia del cynips e il raccolto è ridotto della metà o anche di più.

paolo:

Nella Corsia, negli Stati Uniti e probabilmente nell’Italia, mi chiedo come mai il castagno sia così suscettibile alla malattia.

Geoff:

@paolo Parlando della robaccia cinese … la malattia che sta rovinando le castagne dalle nostre parti si chiama ‘la vespa cinese’! Che io sappia, loro depongono le sue uova sugli alberi, e poi trasformano le gemme dei castagni in palle (galle) in cui si sviluppano e di cui si nutrono le sue larve.

Esiste una cura naturale nella forma di un parassita (Torymus sinensis) che mangia le larve delle vespe, ma viene a costare molto, quindi non va adoperato nelle zone più o meno abbandonate, come la nostra. Pero, è efficace, e si dice che nel giro di 6 o 8 anni gli alberi si riprendono completamente.

Vedere i castagneti d’estate, con le foglie tutte deformate, e poi la mancanza di frutta che c’è d’autunno è una vera tristezza. Speriamo bene per il futuro.

Mamma:

Absolutely fascinating. Shall do a print-off and show to anyone interested!