Roman Medicine Posted by jamie on Mar 20, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit XIV of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

It would not have been a very good idea to get sick in Ancient Rome. Though they were aware of many of the diseases we know about today—including cancer, which the poet Ovid called ‘the incurable evil’—because germs hadn’t yet been discovered, there was little that doctors could do about them. They did their best with food, herbal remedies, and sometimes surgery, but most recovery was dependent upon the patient’s immune system.

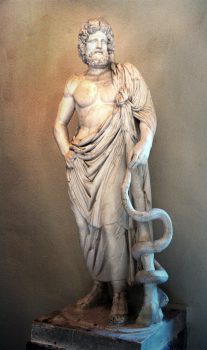

Aesculapius

The Greek god of medicine was Asclepius, who was borrowed by the Romans with the name Aesculapius. His symbol, a staff with a snake twined around it, is still the symbol of medicine today. Temples built to him, called Asclepia or Aesculapia, were the first sort-of-hospitals in Greece and later on in Rome.

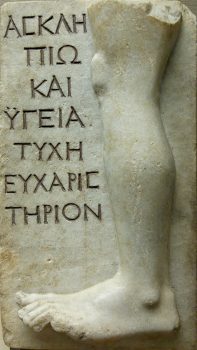

As we’ve seen, the Romans believed that powerful forces, both good and bad, were everywhere. Often, instead of or in addition to seeing a doctor, sick Romans would make small statues of whatever ailed them—hands, eyes, ears, guts, genitals, feet (a truly incredible number of feet)—and offer them to Aesculapius with a prayer, in the hopes that he would cure the injury or disease. If it worked, the happy patient would sometimes write a rave review and leave it by the temple; if it didn’t, well…

Greek Doctors

The Romans were obsessed with Greece. They copied or outright stole Greek art, Greek poetry, and Greek religion, so naturally, they imported Greek medicine. And they imported Greek doctors, too, usually against the doctors’ wishes. Almost all the Greek doctors in Rome, at least at first, were slaves. They were highly respected and well-treated compared to, say, farm workers, but still: slaves.

Almost all books on the medicine used in Rome were either written in Greek or copied from Greek books. The most famous Roman writer on medicine was a doctor named Galen, who was, however, Greek and wrote only in Greek. Latin writers on medicine, like Pliny the Elder and Celsus, were basically just translating Greek information into Latin. One Latin writer who didn’t do this was a grumpy fellow named Cato the Censor, who hated the Greeks and wrote his own book on home remedies. Cabbage figures big.

Humoral Theory

The fundamental theory behind Greek and Roman medicine was humorism (from the Latin word humor, meaning ‘liquid’). This theory said that there were four humors in the human body: red blood, yellow bile, black bile, and white phlegm. A person would ideally have a perfect balance between the four, but most people were believed to have more of one than the others, which caused different types of personalities. A person with more blood (Latin sanguis) was optimistic, a person with more yellow bile (Greek kholē) was angry, while excess black bile (Greek melaina kholē) caused sadness, and too much phlegm made you apathetic and sluggish.

Food and weather could affect the level of each humor, so doctors would often prescribe certain kinds of food to balance out a patient’s humors. For example, since phlegm was ‘cold’, it needed to be balanced with ‘hot’ foods, like garlic and onions.

This theory was incredibly influential. Medieval Islamic doctors read these Greek texts and adapted humorism. In Europe, it was the basis of medicine into the 17th century. Humorism isn’t part of our medicine anymore (thankfully), but it’s still part of our language: a sanguine person is cheerful, a choleric person is angry, a phlegmatic person is unemotional, while melancholy is a synonym for depression.

Selection of Roman Cures in No Particular Order

And how exactly did Roman doctors help their patients? Read on, but don’t try these at home. Seriously, don’t.

For stomach cramps: Soak cabbage in water, then boil until soggy. Pour out the water, add salt, cumin, ground barley, and oil. Heat up, then let cool and eat. If you’ve got a fever as well, drink some water. If you don’t have a fever, drink some red wine with a little water. (from Cato the Censor)

If you’re having trouble urinating: Cook cabbage in boiling water for just a few minutes, then add a lot of oil and a little bit of salt and cumin. Drink the broth cold and eat the cabbage. Do this once a day until you feel better. (Cato, again. I told you he was big into cabbage)

If your tongue is dry or scabby: Scrub it with a brush soaked in hot water, then gargle a mix of honey and rosewater. (from Celsus)

If your shoulders hurt: Vomit black bile. (Celsus)

If you have a headache, hazy vision, red eyes, and an itchy forehead: Have a doctor bleed you. (Celsus)

If you’re seeing hallucinations: Take black hellebore to defecate, if the hallucinations are depressing; take white hellebore to vomit if the hallucinations are happy. (Celsus)

If you’re extremely, insanely sleep-deprived but still can’t fall asleep: Shave your head, rub your scalp with a poultice of vinegar and boiled leaves. Sniff mustard to alleviate the symptoms, or rub it on your head to cure the disease entirely. (Celsus)

One thing I’ve never understood is why the Romans continued to use such strange cures. Was there a kind of placebo effect? Did they work just often enough that people continued to trust them? Or was medicine thought of as a kind of magic? I don’t know. What do you think?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.