A Day of Debate at the Senate Posted by Brittany Britanniae on Oct 4, 2016 in Roman culture, Uncategorized

Salvete Omnes! If you’re in America or if you live anywhere which has media coverage for America you might be feeling quite surrounded by coverage and speculations concerning the Presidential debates. Let’s take a break from modern, televised debates of today and instead look back at the practice, and, indeed, the art of debating in Classical times.

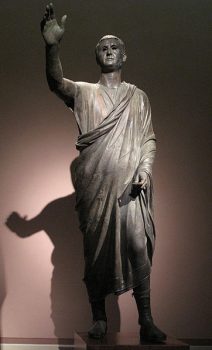

Aule Metele is a Romano-Etruscan work in the Roman style and depicts an Etruscan man wearing a short Roman toga and footwear. His right arm is raised to indicate that he is an orator addressing the public. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In Classical times, the ability of a person to present themselves in discourse and debate comprehensively and perhaps even poetically was quite important. It was also important, of course, to win debates. Persuasiveness was a skill that was admired and sharpened diligently by those who often engaged in debate.

Cesare Maccari (1840–1919) “Cicero Denounces Catiline” Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Cesare Maccari (1840–1919) “Cicero Denounces Catiline” Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A place that held the most heated and significant debates in Roman society was the Senate. If a magistrate wished to call the Senate to meet, he would have to issue a cogere, a compulsory order.

At the meeting of the Senate there would always be a presiding magistrate. Who this was would vary, it would have usually been the consul (the highest ranking magistrate). The consul was the highest elected political office, considered at the top of the of the sequential order of offices someone could aspire to rise through. This sequence of offices was called the cursus honorum.

Another person who could preside was the Praetor (second-highest, the word indicates “a man who goes before others”) if the first was unavailable. In later times, the plebeian tribune was a Senatorial office, the first office, open to the plebeians. This tribune could preside over the senate and speak the will of the people and even veto legislation.

A typical day at the Senate often started at dawn. The men of the Senate would file into the building just as the sun would rise and the air would start to warm up. When seeing a group of magistrates and Senators together it would be easy to notice the similarities in their dress. They all wore the toga praetexta, which was off-white and had rich purple borders. The width of these borders would denote their particular office.

Roman in toga praetexta. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On a festival day, the magistrates might trickle into the Senate at different times later in the day since there were many distractions and duties to be dealt with on those exciting days. Despite this, it was understood that answering the cogere was very important. A magistrate could lose their office if they did not show up for their senatorial duties. Cicero had been threatened with this by Mark Antony at one point.

Curia (or Curia Julia), the Restored Senate House of Ancient Rome, in the Roman Forum, Rome, Italy. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

But as soon as everyone, or at least most, were present, the day of debating would begin. The first item on the agenda would be the verba fecit. The one who is presiding over them would quiet the crowd as the men found their seat and speak to them all to open the session. The presiding magistrate would then pose of the day to the Senate and the talking would begin. However, this started very structured. The princeps senatus, the “leader of the Senate”, was the most senior member of the Senate and was the first to speak. Following him, was the consulares (former consuls), and then the praetors and ex-praetors (praetorii). After them, everyone had a chance to speak in the order of their seniority. You could imagine how this could be a lengthy and repetitive process; the young magistrates would scarcely have more original contributions to offer by the time their turn came up. This dynamic was seen as appropriate.

No vote could be done until everyone in the room had spoken and spoken in the appropriate order. However, a vote had to be completed by nightfall. What this meant was that a Senator might take advantage of these limitations. Much to the chagrin of other Senators, if one man did not want a popular law to be passed he might delay the vote on the law by simply talking. Today, we call this filibustering, in Classical times this was called a diem consumere, because he could consume the day away and keep the vote from happening. The other men, no matter how much they wanted the law to pass, had to sit and grumble the day away as another Senator spoke and spoke about trivial things to make the time tick by. Booing, cheering, or heckling was certainly allowed. This often made the debates very loud and difficult to manage and also quite easy to get off topic if a Senator or two were to get into an argument about a tangent concern.

Bronze doors of the ancient Roman senate taken from the Roman forum and restored and placed in 1660 in the Lateran basilica. These doors would have been left open as the Senate met. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On a day like this, if a member of the public wandered in, as they could since the doors were left open all day, they may have wanted to silently observe legislation in process, but have found that nothing that day was going to get done because of these tactics and simply have walked back out – probably to the envy of some Senators stuck there.

This was not the only frustration that could occur in the Senator house. An unpopular presiding magistrate could be held up by the Senators calling for a “consule“, a consult, which required that opinions be shared at length. Another way of time-wasting was if the Senators cried “numera!” , after which the presiding magistrate had to do a quorum call. You might recognize this tactic if you ever had a substitute teacher – have they do roll call the long way and you’ve wasted a good chunk of time.

Although Julius Caeser enacted a law that would require the Senate to publish their proceedings and resolutions, these were called acta diurna, in order to discourage the abuse of these tactics, the Senate was a place where the art and legends of powerful Classical debate rhetoric met schoolyard spite and manipulations. A day at the Senate must have been both exhilarating and exhausting – a historian can only imagine.

Review the Vocabulary!

cogere

consul

cursus honorum

Praetor (praetorii)

plebeian tribune

toga praetexta

verba fecit

princeps senatus

consulares

diem consumere

consule

numera

quorum call

acta diurna

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Brittany Britanniae

Hello There! Please feel free to ask me anything about Latin Grammar, Syntax, or the Ancient World.