Ancient Roman Super Stars: Charioteers Posted by Brittany Britanniae on Jan 28, 2014 in Latin Language, Roman culture

Good Day Readers! So, let’s talk about some sports since the Olympics and the Super Bowl are just around the corner. While the Olympic Games were “the” competition of Ancient Greece; the chariot races were the oldest and most popular spectacle of Ancient Rome. So, we all know the iconic chariot scene from Ben Hur, but how many of you know what is inaccurate about it? Read on! http://youtu.be/kxcMwRdNuTk

An Average Race

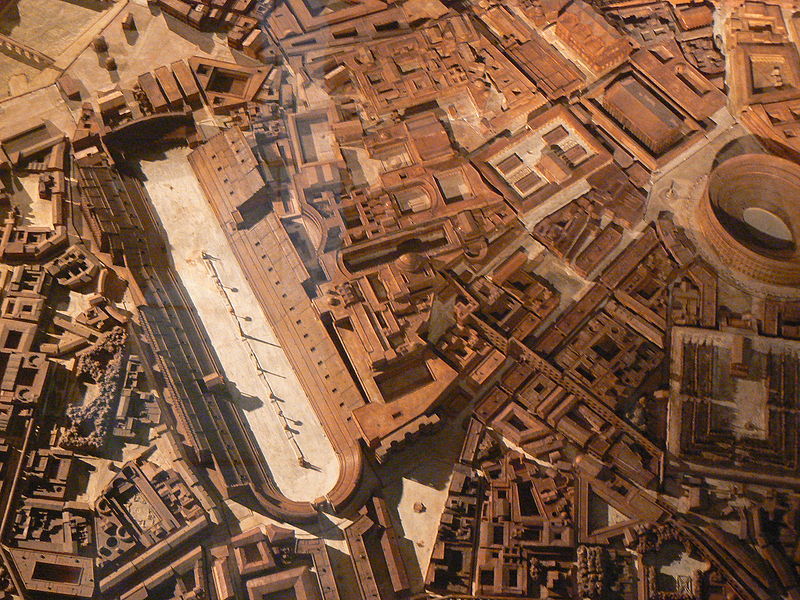

Model of Rome in the 4th century AD, by Paul Bigot. The Circus lies between the Aventine (left) and Palatine (right); the oval structure to the far right is the Colisseum

They normally began with a pompa (procession) which started atop the Capitoline Hill and went through the Forum and Sacred Way and back towards Form Boarium, The carceres (starting gates) of the Circus Maximus (which could hold 250,000 people) abutted the Forum Boarium. The emperor or triumphator headed up the pompa riding in a biga or quadriga (2 or 4 horse chariot) and dressed as a triumphant general. Then the editor presiding over the games would follow along with a group of elites, then the drivers and chariots. These were usually serenaded by musicians. Then the priests with their ritualistic displays would enter last with statues of the gods on carts (depending on which festival and god was being honored).

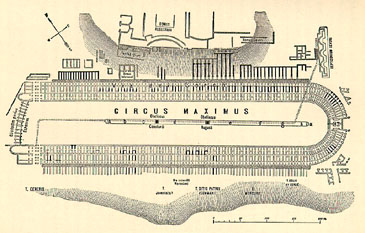

Ground plan of the Circus Maximus, according to Samuel Ball Platner, 1911. The staggered starting gates are to the left.

Once the pompa was finished. The racers in their chariots would take their places behind the carceres. The races began at the dropping of a mappa (cloth) by a magistrate from the imperial box or above the starting gates. Races were held between quadrigae (four horse chariots) ;although other sizes were also used like the two horse chariot or even the rare ten horse chariot. Chariots were made from wood and leather in order to be light and maximize handling. Accidents were known as naufragia or shipwrecks. Naufragia and last-minute surges from behind were the most exciting features of a race.

Technique

Roman drivers steered their chariots using their body weight. They would tie the reins around their torso and lean to whichever side they desired to turn. This was done in order to free up their hands in order to use a whip or whatnot. Once the race had begun, the chariots (sometimes teams belonging to the same color faction) could move in front of each other in an attempt to cause their opponents to crash into the spinae (the long divider with statues and the obelisk). On the top of the spinae stood small tables or frames supported on pillars, and also small pieces of marble in the shape of eggs or dolphins (as seen in the Ben Hur video). At either end of the spina was a meta (turning point) in the form of large gilded columns; this is where commonly crashes happened. Colors

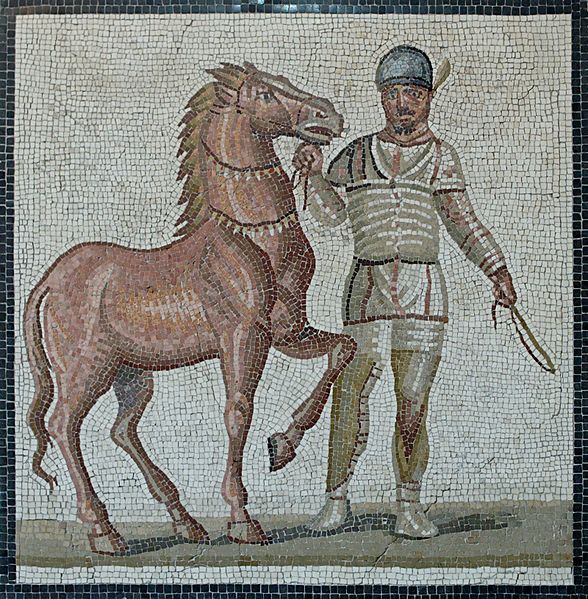

A white charioteer; part of a mosaic of the third century AD, showing four leading charioteers from the different colors, all in their distinctive gear.

There were factions (factiones) or teams for chariot racing (each color allowed 3 chariots in a race): russata(Red), albata (White), veneta (Blue), and prasina (Green). The origins of these colors and their meanings have been lost over time, but their original use was so that charioteers would be discernible from afar. The groups were broken into rivals of Reds vs. Whites and Blues vs. Greens. These rivals ultimately sparked hate, destruction, and intense competition between racers and fans. Slowly through the empire, the Reds and Whites were overshadowed by the popularity of the Blues and Greens in artifacts, inscription, and literature. Emperor Domitian created two new factions, the Purples and Golds, which disappeared soon after he died. To see the entire mosaic click here.

Racers or Charioteers

Racers were color coded in accordance to their faction or team. The charioteer wore a short tunic wrapped with a fasciae (padded bands) to protect the torso as well as around his thighs. They also wore a leather helmet and carried a falx (a curved knife) which they could cut the reins and keep from being dragged in case of an accident. Roman charioteers themselves, the aurigae, were considered to be the winners, although they were usually also slaves. They received a wreath of laurel leaves, and probably some money; if they won enough races they could buy their freedom( as could gladiators). Drivers could become celebrities throughout the Empire simply by surviving, since the life expectancy of a charioteer was not very high.

Winners & Famous Charioteers

Victorious racers were awarded prize money in addition to the contractual pay arranged in advanced (by the sponsor of the games). Racers also performed and raced in more than one race per day (on a festival or ludi), so some charioteers could earn a fortune! Pliny the Elder recounts the unusual result of a team of horses winning the race even though the driver was knocked off. Pliny attributes the winning to “equine pride” and Pliny’s example shows the benefits to repetitive training. One celebrity driver was Scorpus, who won over 2000 races before being killed in a collision at the meta when he was about 27 years old. The most famous of all was Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. When Diocles retired at 42( after a 24 year career and switching from White to Green to Red) his winnings reportedly totalled 35,863,120 sesterces ($US 15 billion), making him the highest paid sports star in history!

Horses

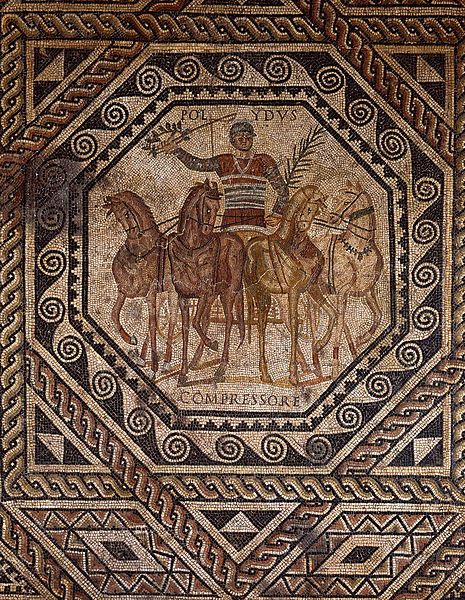

Mosaic naming Polydus the charioteer and his lead horse, Compressor. Rheinisches Landesmuseum Trier.

Horses were worthy of reputation and respect for their prowess in a race. Even the famous charioteer Polydus’ horse, Compressor, was depicted in mosaics( above). A quadiga‘s lead horse was the focus of attention for fans, charioteers, and gamblers. If a racer’s lead horse seemed unsteady or skittish then fans and sponsors would less likely bet or support that particular charioteer. However, if a horse was well respected they would receive honors or even curses by competitors. [Sources for curses against charioteers and their horses can be found here]. Examples of horses being honored include Emperor Caligula’s Incitatus (once a race horse), the horse known as Volucer (meaning winged one) was a favorite of Emperor Lucius Verus, and Tuscus who was favored by Diocles (with whom he won 429 races). Mares were rarely used for the lead horse, but they were used for the inside positions. The Romans kept detailed statistics of the names, breeds, and pedigrees of famous horses.

Fans & Fan Clubs

Just like the loyalty of modern day fans, Ancient Roman fans or supporters of the Red, Blue, Green or White factions were intense. Pliny records one Red fan threw himself unto the funeral pyre of a Red charioteer known as Felix, and how the opposing fans tried to prevent this story to be recorded and asserting that the man fainted and fell in. Furthermore, each faction color had their reserve seating for their color so that fans could in engage in chanting, activities, and sneers uniformly. Eventually extreme fans became an issue in the Empire when their color lost; riots would ensue. Sometimes these riots and revolts were sparked by a loss (or blamed on one), but often had political undertones such as the Nika Revolt.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Brittany Britanniae

Hello There! Please feel free to ask me anything about Latin Grammar, Syntax, or the Ancient World.

Comments:

blazeaglory:

Excellent!

Nan:

I think in Ben Hur, they used the reins as they did because they probably weren’t experienced enough to do otherwise. After all, Charlton Heston was taught how to drive for the movie. They built a second race course near the one they filmed in for training everybody.

Also, the competition between the Blues andGreens went on to Constantinople, and eventually one of the colors had a subdivision into the Blacks and the Whites in the Middle Ages in Italy. And the whites divided into the Guelfs and the Ghibellines in Dante’s time.

Thanks for the great info. I enjoyed this very much.

And I envy Charlton Heston cuz he got to drive chariots.

David Randall:

A very interesting, informative and accurate article – except for the bit about Diocles. This business about his career earnings equalling $15 billion is everywhere, and is sheer nonsense. We know quite a bit about the man; his full name was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, and he came from Lusitania, modern day Portugal. For purposes of clarificaton, I’m going to round off his career winnings to 36 million sesterces. A sestertius was a large bronze coin worth 1/4 of a denarius. A denarius was a small silver coin a little larger than a dime. 36 million sesterces = 9 million denarii. Now, the daily wage for an unskilled worker at the beginning of the 2nd Century AD was one or two denarii per day. Let’s take the most generous interpretation and say it was one denarius. Today, an unskilled worker might earn, say, $100 a day (this is more than minimum wage). So, $100 x 9 million denarii = $900 million. A lot, but nowhere near $15 billion. My estimate of Diocles’ career earnings would be closer to $500 million in 2014 dollars.

jef:

I like kechup with my chips!!!

Marlen Oshima:

Rattling instructive and fantastic anatomical structure of articles, now that’s user friendly (:.