City Life and Country Life in Ancient Rome Posted by jamie on Apr 9, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit VIII of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

Ancient Rome was both a highly urbanized civilization and a very rural one. Large, dense cities sat in the middle of vast oceans of farmland—there weren’t suburbs then like the ones we have today. And many of the differences between city and country life that we experience today existed then, too.

City Life

For a Roman city-dweller, how comfortably you lived depended—like it always has—on how much money you had. The rich lived in enormous townhouses called praedia, some of them with vast private gardens, close to the Forum in the center of the city. The emperor’s private residences occupied an entire hill. In the summer, when Rome became unbearably hot, the privileged would retreat from the city to their houses in the country or by the sea.

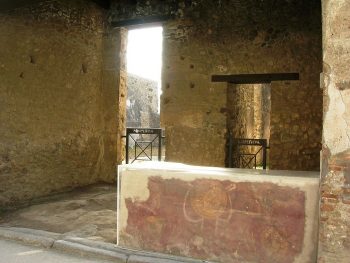

For the poor, life was very different. They lived not in praedia but in insulae, cramped apartment buildings without kitchens or running water. Instead of cooking, most people bought food from snack stands called tabernae or popinae, which served hot, cheap meals. Others might take their share of the Annona—flour that was given for free or for very cheap to Rome’s poor—to a baker and have it baked into bread.

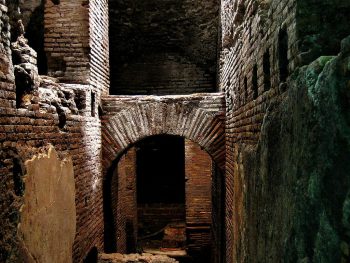

These insulae were cheaply and dangerously built. They were made partly of wood and constructed right next to each other. When fires spread through Rome, as they often did, the insulae turned into kindling. Rome had no firefighters until 60 AD when Nero created the vigiles, who patrolled the streets keeping a watch out for small fires. Before then, there had been for-profit fire brigades, who would put out fires—if the residents of the burning buildings could pay. (Ironically, many people believed then, and many people still believe, that Nero deliberately set fire to Rome so he could build himself an enormous mansion on the ashes)

Like all cities, ancient Rome was notoriously loud and crowded. The poet (and legendary grump) Juvenal complained about vendors clogging up the streets, while the philosopher Seneca whined in a letter to his friend Lucilius about the grunts of the bodybuilders coming from the gym below his house.

Country Life

In their poetry, Romans imagined that country living was a relaxing fantasy: pastores, or shepherds, would lie around under trees, singing songs and flirting and generally doing no work at all. The poet Vergil wrote a series of poems called the Eclogues, imagining the simple lives of country-folk, and his friend Horace, also a poet, wrote often of his modest country home (while living in a mansion). The lawyer and speaker Cicero, who spent nearly his entire life in the city of Rome, once wrote that “of all the occupations by which gain is secured, none is better than agriculture, none more profitable, none more delightful.”

The reality was of course quite different: then as now, farming was an incredibly difficult way to make money, and poor farmers would eke out a living on small plots, raising some crops and some livestock.

Far easier (for the owner) was life on a latifundium, or a large farm, which would, of course, be the property of a wealthy individual. The dominus (master) and his family would live in the villa, or large country house. The actual running of the farm was doing by a vilicus—the overseer or bailiff—and the work itself, naturally, was done by slaves. Major crops were wine-grapes, olives, and wheat.

The monotony of farming was broken up throughout the year by holidays, many of which involved animal sacrifice, and therefore a chance to eat meat. One of the most significant of these holidays to ancient landowners would have been the Terminalia, the feast of Terminus, god of boundaries. Landowners would meet at a designated stone on the line between their two properties, and cover the stone with flowers, wine, and honey, before sacrificing a pig.

Although farming was difficult—for those who did the actual work—it was also the best way at the time to gain wealth. As a result, generals and emperors would reward veterans soldiers with plots of land. Because of the difficulty of making a living from farming, however, it’s likely that many of these farms ended up being sold to the owners of latifundia.

Whether you grew up in the city or the country, some of this must seem familiar to you. Still, a lot has changed. Even cramped modern cities are much more open than ancient Rome was, and even remote parts of the country are more connected than they used to be. For the most part, fires no longer devastate cities, and farms are no longer worked by slaves. There are similarities, though—what similarities do you see?

Glossary of Greek and Latin Words and Phrases

Annona — a kind of welfare or dole, where flour was given out or sold for cheap to the poor

Dominus — master of an estate

Insula — an apartment building; literally an ‘island’

Latifundium — large farm

Pastor — shepherd

Popina — snack stand

Praedium — a mansion, either in the city or the country

Taberna — tavern

Terminalia — The February 23rd holiday celebrating Terminus, the god of boundaries

Vigiles — ancient firefighters

Vilicus — overseer of a farm

Villa — house on an estate

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Rom:

Latine studium fecit Romae (1957 – 1960).

Laureatus in Philosophia.

Gaudeamus igitur….

JOAN BLAZEBY:

I LOVE FINDING OUT EXACTLY AS FAR AS WE KNOW WHAT WENT ON