The Roman Family Posted by jamie on Mar 8, 2019 in Intro to Latin Course, Roman culture

Note: This blog post is a companion to Unit XII of our Introduction to Latin Vocabulary course. You can learn more about the course here.

A few weeks ago we had a look at the Roman household. Let’s follow up on that now, looking at the Roman family’s place in the larger context of Roman society

Familia Romana

The Latin word familia doesn’t translate directly to the English word ‘family’. In fact, there is no single Latin word which could be translated into our ‘family’. Instead, the Romans had at least three words that capture different parts of our idea of family: gens, domus, and familia.

The gens was a sort of clan or tribe, consisting of all the people who shared a common nomen, or surname. Gentes varied widely in both size and status—some were quite small, while other included dozens of households; some were plebian, some patrician, and some divided into plebian and patrician branches. The status of your gens determined your status as an individual.

The domus (literally ‘house’) was the closest thing to our ‘nuclear family’, and was using to describe a single household within a gens. The father and children in the domus belonged to the father’s gens; the wife of the household, however, usually still belonged to her own gens.

Finally, the familia included all the people who lived in a home—slaves included. Almost all free families that could afford them owned slaves, and rich families might own hundreds. Slaves who lived and worked in the home were considered an intimate, although inferior, member of the family, and their relationship with the family didn’t end even if they were freed, as we shall see.

Nomina

A Roman’s nomen, or name, contained a wealth of information about their family, social status, and life history. Even today, just by reading a Roman’s name, we can learn a tremendous amount about them.

Traditions varied over time, but by the 1st century BC most Roman men had three names. The praenomen was their first name, and there were only about a dozen in common use: Aulus, Decimus, Gaius, Gnaeus, Lucius, Manius, Marcus, Postumus, Publius, Quintus, Septimus, Sextus, Tiberius, Titus. In other words, pretty much all guys had the same first name. The Romans weren’t big on individualism.

The nomen or nomen gentilicium was the name of the gens; this was the name that let everyone know who you were related to, and therefore how important you were.

The cognomen was the last of the three names. Originally this was a kind of nickname (often negative, like ‘Warty,’ ‘Dummy,’ ‘Baldy’), but eventually many cognomina were passed down along with the nomen. Cognomina could, however, be earned by doing remarkable things—like Pompey being called Magnus, or Publius Cornelius Scipio, who defeated Hannibal, being called Africanus.

You could also gain a cognomen by being adopted. When Gaius Octavius, the future emperor Augustus, was adopted by his great-uncle Gaius Iulius Caesar, his new name became Gaius Iulius Caesar Octavianus—his old nomen became his new cognomen.

Women were not given either praenomina or cognomina; they just took the feminine form of their father’s nomen. So the daughter of a man named Gaius Claudius Verrucosus would simply be called Claudia; if she had a younger sister, the sister would named Claudia Secunda— ‘Claudia number 2’.

Clientela

Roman families of higher and lower status were connected by a system called the clientela. A wealthy Roman man could be a patronus to many (sometimes hundreds) of lower-class men, who were his clientes. The patronus had an obligation to protect and support his clientes with gifts and money, while the cliens had an obligation to vote for his patronus and even support him in battle. (As the Roman Republic fell apart, rich Optimates and Populares would send mobs of clientes to fight in the streets of Rome). The cliens was a kind of junior member of the patronus’ gens.

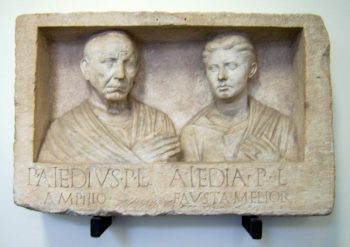

When a slave was freed, which happened more often in Ancient Rome than it did in America, he automatically became his former master’s cliens, and took his patronus’ nomen. For example, if a man named Patroclus had been enslaved by a man named Marcus Servilius, Patroclus’ new name after being freed would be Marcus Servilius Patroclus, with the letters M.L. added, meaning ‘Marcus’ freedman’. You weren’t ever allowed to forget that you had been a slave.

Ancestor Worship

The close bonds of the Roman family didn’t end in death. Every Roman family worshiped their dead ancestors as spirits called Lares, who were thought to literally live in their home. They even had a little shrine to the Lares, called the Lararium, in the main room of the house.

In the middle of February was a long holiday, called the Parentalia, in which the Romans would leave offerings of flowers, food, and wine at their family graves. It was believed that if they didn’t do this the dead would rise and walk howling through the streets and fields of Rome.

The Romans feared the dead as much as they worshiped them. While the ‘good’ dead were called Lares, the ‘bad’ or scary dead were called Lemures or Larvae, and instead of giving them offerings the Romans tried to scare them away. In the middle of May, during a holiday called the Lemuria, the father of the family would have to get up at midnight, pick up a bowl of beans, and walk barefoot through the house throwing the beans behind him; then he would bang pots and pans together as loudly as possible while screaming, “BEGONE, ANCESTRAL DEAD,” nine times in a row. It was an awkward family relationship.

We often like to draw parallels and highlight the similarities between the past and the present, but in this case Roman culture was simply vastly different from our modern American culture. The importance of the family, the non-importance of the individual, the intimate relationship with death, a person’s life story being literally written in their name—these aspects of Roman culture are almost the exact opposite of what we have in American culture today. What do you think? Does this seem like a society you’d feel at home in?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.