Reading «Мастер и Маргарита»: Chapter 2 Posted by josefina on Jun 14, 2010 in Culture, History, language, Soviet Union

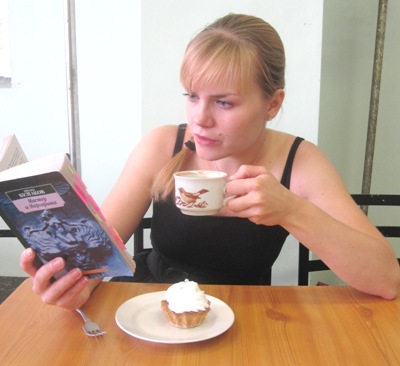

Where has your copy of «Мастер и Маргарита» [“The Master & Margarita”] been this week? I brought mine with me to the «университетская столовая» [university canteen] where I read it together with «кофе» [coffee] and «корзиночка со сливками» [lit. ‘little basket with cream’] a very tasty Russian pastry.

Chapter 2 «Понтий Пилат» [“Pontius Pilate”] of M&M (that’s what Yelena and I have come to call the novel in our personal correspondence lately; not to be confused with the candy with the same name!) begins already at the end of chapter 1 when the «профессор» [professor] also known as the «иностранец» [(male) foreigner] and a «специалист по чёрной магии» [specialist on black magic] – only later in the novel is his name «Воланд» [Voland, or Woland] revealed – says that «доказательств никаких не требуется» [no evidence is necessary] to prove that Jesus existed and then pronounces a sentence to Berlioz and Bezdomny, which is also the first sentence of chapter 2. In early editions of “The Master & Margarita” this chapter was called by «Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков» [Mikhail Afanas’evich Bulgakov] himself «Евангелие от Сатаны» [“Satan’s Gospel”]. In this chapter we’re introduced to the ‘second’ plot of the novel which is a highly important side story that will be repeated many times within the novel’s ‘first’ plot. The first plot takes place in Moscow in the 1930’s – as we have already learned from Yelena’s excellent post about chapter 1 – and where and when does the second plot take place, then? It is set in the town of «Ершалаим» [disguised under this name is obviously the city of Jerusalem] where we meet «Понтий Пилат» [Pontius Pilate] who is «прокуратор Иудей» [prosecutor of Judaea] and also rather human as he is suffering from a vicious headache at this time. The second chapter of “The Master & Margarita” describes his meeting with a certain «подследственный из Галилеи» [person under investigation from Galilee] with the name «Иешуа Га-Ноцри» [Yeshua Ha-Nozri]. He is about the face the death sentence because he «подговаривал народ разрушить ершалаимский храм» [incited the people to destroy the temple of Jerusalem]. Does this remind you of anyone we know? Of course, it is none other than our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ! But in “Satan’s Gospel” Yeshua is portrayed very different from what we can read and learn about Jesus’ meeting with Pontius Pilate in the New Testament. The problem of similarities and dissimilarities between Yeshua as a character in “The Master & Margarita” and Jesus Christ as portrayed in the Bible has caused a mountain of scholarly work to be conducted and completed in many languages worldwide. For example, my second roommate here in Yekaterinburg (from USA) wrote her «бакалаврский диплом» [Bachelor’s thesis] on this problem and did such a good job that she received not only the grade «отлично» [excellent] but a «красный диплом» [red diploma (the equivalent of graduating with honors)] upon completing the BA program. So if you find yourself confused at times while reading this chapter, then that’s alright and as it should be. The entire ‘second’ plot of this novel is confusing at times – though equally entertaining and very thoughtful in its posing of philosophical questions – and can be given many different interpretations. You shouldn’t force yourself to ‘get it’ straight away. If you’re the person who always wins when playing Bible trivia, you can read it slowly and considerately while comparing it in detail with the New Testament. If you haven’t read the Bible at all, then why not just enjoy some almost historical information imbedded in excellent artistic narration?

In the chapter, Yeshua says that his one and only «ученик» [disciple] «Левий Матвей» [Matthew Levi] is writing down his words all wrong and that this has caused the people to misinterpret his intentions. He explains to Pontius Pilate: «-Эти добрые люди, <…> ничему не учились и всё перепутали, что я говорил. Я вообще начинаю опасаться, что путаница эта будет продолжаться очень долгое время» [- “These good people, <…> haven’t learned anything and have got everything wrong that I said. I am actually starting to fear that this mess will continue for a very long time”]. Here Bulgakov is, of course, hinting not without irony at The Gospel of Matthew… which according to «безбожники» [pl. godless people; atheists] of the Soviet Union did indeed create “a mess that continued for a very long time” in the world.

Chapter 2 is one of the longest chapters in the novel (in my copy it stretches over more than 25 pages) and can thus cause some trouble for the inexperienced in reading Russian novels «в подлиннике» [in the original]. From my own experience with learning how to read Russian novels the hard way – by going through hundreds of them in the original ever since my ‘first’ back in the spring of 2005 (which was «Записки из Мёртвого Дома» [“Notes from the Dead House”] by «Достоевский» [Dostoevsky]) – I have come to the conclusion that it is never «целесообразно» [advised; expedient] to look up every new and yet unknown word in the dictionary. Some people would say it is not recommended at all for anyone to even try and read a whole Russian novel in the original before having studied the language for more than a year. Well, I had studied Russian for about 8 months when I started my journey into the 19th century «каторга» [penal servitude; hard labor] as depicted by one of Russia’s greatest writers EVER. And what lesson did I learn? First and foremost that most writers have a certain amount of words that they use and these words are often repeated throughout their books. Now Bulgakov is a bit more advanced in this area than Dostoevsky (no offense, Fyodor Mikhailovich – just telling it like it is) and uses a larger amount of words and does more wordplay than many other Russian writers. In this sense he is true to his own literary ‘Master’: «Николай Васильевич Гоголь» [Nikolai Vasil’evich Gogol’]. Bulgakov is in many ways the Gogol’ of the 20th century and his works are filled with allusions to and quotations from his 19th century predecessor. “The Master & Margarita” is no exemption from this rule, I’m afraid. But you shouldn’t be afraid! Not the least!

The best way to begin to read a Russian novel in the original if you’re still not very experienced in this area is to make the «словарь» [dictionary] your constant companion only during the first chapters. Keep track of the words you have looked up while reading by writing them into a smaller notebook. In this way, you can return to it and repeat some of the words later. And also know that these words are bound to be repeated throughout the novel. Once you get farther into the work of fiction, don’t stop your reading every time you come upon a new word to look it up in the dictionary. Underline it – that’s always a great way so as to be able to return to it – and try to understand it from the context. Generally speaking, you don’t need to understand EACH and EVERY word in a novel in order to enjoy it. Remember that it is okay to guess, and that it is just as okay to only later understand fully what you read earlier. If your Russian is more advanced, you should read one chapter at a time – or why not ten pages – and underline new words as you go along. Then you go back and look up ONLY the words that you can’t fathom by way of getting the context surrounding them. It is not ‘bad’ or ‘lazy’ not to look up ALL words. Nobody’s perfect, after all, and neither should you ever try to be. Literature is not a contest of who gets it better or understands it deeper – but a journey through opening up things yet unknown. Not to mention that it is a great way to educate oneself and learning about people!

While reading “The Master & Margarita” I bet we’ll all come not only to find out more about Russia in the 1930’s, but also about ourselves. Literature is about people and people who love literature tend to have a great love for people. And because we’re all people here (well except for «кот Бегемот» [Begemot the cat], at least that’s what my interpretation of this character has come to) then that’s what our focus should be on: ourselves and each other!

I don’t know about you, but personally I’m so wrapped up by this novel now that I can’t wait to visit «музей Булгакова» [the museum of Bulgakov] next week while in Moscow… I promise a post about this exciting adventure in a very soon future!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Kurt Pogue:

«Мы читаем «МастерА и МаргаритУ» вместе» [We read “The Master & Margarita” together]. does this mean more like os as the same as, [We are reading “The Master & Margarita ” together]? The present tense? I am still trying to teach myself Russian.

Jan Vanhellemont:

About Yershalaim: Bulgakov uses an alternative transliteration of the Hebrew ירושלים (Yeru-shalayim) for the name of the city of Jerusalem. In certain other cases as well, Bulgakov has preferred the distancing effect of these alternatives: Yeshua for Jesus, Ha-Nozri for Nazareth, Kaifa for Caiaphas, Kiriath for Iscariot.