Reading «Мастер и Маргарита»: Chapter 6 Posted by josefina on Jul 12, 2010 in language, Soviet Union

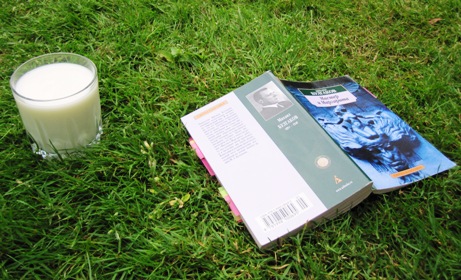

It doesn’t really feel like «лето» [summer] until you’ve spent an entire afternoon doing nothing but the following simultaneously: «лежать в траве» [to lie in the grass], «пить холодное молоко» [to drink cold milk] and «читать Булгакова» [to read Bulgakov]. «Россия» [Russia] is a wonderful country in many, many ways – but during my six years there I wasn’t able to find and buy milk «без лактозы» [without lactose]. Thus «Швеция» [Sweden] is the better choice for anybody allergic to dairy…

If we keep up this slow pace that we’ve been reading our way through «Мастер и Маргарита» [“The Master & Margarita”] since our start in June – one chapter per week – I suspect we’ll finish it only in time for «Рождество и Новый год» [Christmas and New Year]. But who’s in any rush? Maybe being a «тормоз» [1. brake; 2. fig. brake, drag; hindrance, obstacle] – a noun made from the verb «тормозить» [impfv. 1. to brake, to apply the brakes; 2. fig. to hinder, hamper, impede, retard] (or maybe the other way around: the verb was made from the noun – «кто знает?» [who knows?]) – isn’t necessarily a bad thing when it comes to us and «господин писатель Булгаков» [‘mister writer Bulgakov’ (P.S. I think it is safe to say that I’m being ironic when I call «Михаил Афанасьевич» that – do not take after my reckless behavior! Stick with «имя и отчество» [name and patronymic] if you want to show proper «уважение» [respect] and no irony at all)? Maybe our slow pace will as a matter of fact help us to learn even more along than road? Maybe taking things slow isn’t simply cliché or something people say when they’re dating someone but not really that interested, but pretty good advice? Once again, «кто знает?» [who knows?] – only those who stick it out until the end will know for sure! Here to guide you through «глава 6 (шестая): Шизофрения, как и было сказано» [chapter 6: Schizophrenia, as had been said] is a woman who has made a habit of calling herself «тормоз и лох» [‘a drag and a nerd’] before anyone else does it. What does that have to do with today’s chapter in the novel? you might be asking yourself. Well, it has everything to do with it because today’s post will be all about «ругать» [imfv., here: to call names] in Russian. The perfect ‘friend’ of this verb in this meaning is «обругать» [pfv. 1. to curse out, call names; 2. colloq. to criticize, attack, pan]. Why is that important? you wonder. Because chapter 6 is the chapter where «Иван Николаевич Бездомный обругал доктора и поэта Рюхина» [Ivan Nikolaevich ‘Homeless’ called the doctor and the poet Ryukhin names] «в доме скорби» [in ‘the house of grief/sorrow’].

From the previous chapter you might remember that everybody’s favorite poet, famous under the pseudonym ‘Homeless’, turned up one evening in May in the literary organization’s restaurant wearing nothing but underpants, all the while holding an icon and a light candle in front of him. Everyone is was rather surprised and wondered «что случилось» [what had happened]. Berlioz had been killed and Ivan was of course on the hunt after the man who did it – the «иностранец» [foreigner] who «предвидел смерть Берлиоза» [foresaw Berlioz’s death], «знал Понтия Пилата лично» [knew Pontius Pilate personally] and regretted that he didn’t ask what «шизофрения» [schizophrenia] was… Ivan didn’t get any help with that, instead he was sent by his literary colleagues to the «знаменитая психиатрическая клиника» [famous psychiatric clinic] outside of Moscow. And that’s where chapter 6 takes place, while the «доктор» [doctor] and the poet «Рюхин» [Ryukhin] try and figure out «что не так» [what’s wrong] with Ivan. And in this dialogue, we find the following new and interesting words – try and remember them, for who knows when you’ll have to call someone names in Russian in the future?:

Ivan greets doctor with two words: «Здорово, вредитель!» [”Hello there, economic saboteur!”]. And that’s when we know how this poet feels for representatives of the medical profession.

«вредитель» – 1. pest, pl. vermin; 2. economic saboteur.

Then Ivan calls his ‘friend’ and fellow poet Ryukhin «гнида» – 1. nit (louse egg); 2. scumbag, rascal. But that’s not the end of his unenthusiastic feelings toward this person – for soon Ivan elaborates:

«Нашёлся наконец один нормальный среди идиотов, из которых первый – балбес и бездарность Сашка!» [Finally someone normal turned up among all of these idiots, the first of whom is the talentless nitwit Sashka!]. Placing the postfix «-ка» in the diminutive form of a name is always a sign of dislike for this particular person.

«идиот» – idiot.

«балбес» – colloq. booby, nitwit.

«бездарность» – 1. lack of talent; 2. fig. person with no talent (it should be added that to be called «бездарность» in Russian is and feels much more worse than to be called ‘a person with no talent’ in English).

Ivan doesn’t stop there when it comes to giving a detailed description of Ryukhin’s character. He continues: «Типичный кулачок по своей психологии…» [He’s got the typical psychological traits of a little kulak…]. Ouch! In the 1930’s Soviet Union nothing could have been worse than to be called «кулачок». Except the word which is diminutive of: «кулак» [1. fist; 2. hist. kulak (wealthy farmer who takes advantage of his less fortunate neighbors)] – being called that was the first step on a long journey either to labor camps or for your entire family to be forced to move somewhere cold and unpleasant. And Russia was – is? – a huge country with plenty of cold and unpleasant places where one could be put away…

But even when using this clear expression Ivan finds it necessary to elaborate: «…и притом кулачок, тщательно маскирующийся под пролетария» [And moreover he’s a little kulak masking himself carefully as a proletarian]. Ouch again! That must have hurt!

While reading “Master & Margarita” you might find something interesting if you underline the word «чёрт» [devil] every time is used, no matter in what context. You’ll come to see that it is used many, many times in several expressions (three whole times only in chapter 6!) throughout the novel, as if the characters in it were calling the Devil to come to Moscow… The doctor asks Ivan how he was brought to the hospital, at which he answers: «Да чёрт их возьми, олухов!» [lit. ‘Let the devil take them, blockheads!’, or: ‘To hell with them, blockheads!’].

«олух» – colloq. oaf; dolt; blockhead.

Ivan calls the people at the mental hospital «бандиты» [bandits, thugs] before we’re left watching as he’s taken away at the end of chapter 6.

And to finish off the chapter, Ryukhin calls «Арчибальд Арчибальдович» [Archibald Archilbaldovich] «пират» [a pirate]. Not to his face – but still! It is not a very kind thing to think about a fellow human being. Next chapter is «Глава 7 (седьмая): Нехорошая квартира» [Chapter 7: Not a Good Apartment] – I can’t wait! Will we finally be introduced to Begemot?!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.