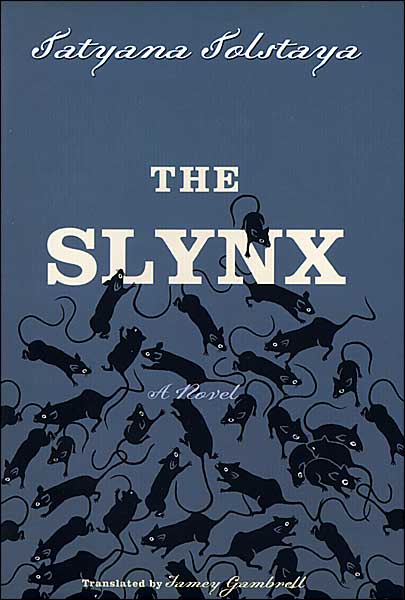

The Slynx Posted by yelena on Mar 23, 2012 in Culture

Book reviews can be very misleading. Actually, if I was to read the reviews for Кысь (The Slynx) by Татьяна Толстая (Tatiana Tolstaya) first, I would have not picked up the book at all. Luckily, I wasn’t looking for anything particular the day I spotted it on the bookshelf of книжный магазин (bookstore) on Brighton Beach.

The novel is translated into English and has collected quite a few readers’ reviews as well. Again, I’m happy I’ve not had a chance to read them beforehand.

Say you do decide to read the novel (and I highly recommend it), either in its original Russian or translated into English. In this case, I’m not going to spoil it for you with yet another unsatisfying and unsatisfactory review. Instead, I’m going to try to be useful with some side notes.

The genre of the novel is what the Russian-language Wiki article defines as этноцентрированная постапокалиптическая антиутопия (ethnocentric post apocalyptic dystopia – gives you nice practice with compound words). But don’t expect artificial intelligence or aliens or monkeys taking over the planet. Всё гораздо тише, обыденнее, проще. (Everything is a lot quieter, more trivial, simpler.) And a lot more familiar too.

One of the long-lasting effects of the never-explained Взрыв (Blast) was the loss of all technological advances and scientific knowledge. The absence of all futuristic technology makes the setting much more recognizable and thus scarier.

If you are used to the types of stories that revolve around an uncommonly handsome hero facing challenges, overcoming adversity, triumphing over the circumstances all the while finding the girl of his dreams, this story will take some getting used to. Yes, the uncommonly handsome, un-mutated, untouched by Последствия (Consequences) hero is there. And the lovely girl is there too. The challenges, however, are far from epic. As for the circumstances… Well, всё хорошо, что хорошо кончается (all’s well that ends well) is not exactly the stuff of dystopias. Although the ending is surprisingly neither bleak nor hopeless.

The words голубчик (for males) and голубушка (for females) (lit. my dear or my darling) are used in the book a lot to describe pretty much any regular, ordinary person. It’s a common form of address in Фёдор-Кузьмичск (Fyodor-Kuzmichsk, the name of the village where the novel takes place). The way it’s used t is very similar to товарищ (comrade) address of the Soviet era. While голубчик is a ласковое (tender) word, as a form of address it is both устаревший (outdated) and betrays a level of contemptuous фамильярность (familiarity).

The интеллигенция (intelligentsia) survivors of the Blast are known as Прежние (lit: former) or, in English translation, the Oldeners. In Russian, the word интеллигентный (intellectual, cultured) has a positive connotation as in Мне нравится твой новый парень – такой интеллигентный! (I like your new boyfriend – so cultured!).

However, the nouns интеллигенция (intelligentsia) and интеллигент (member of intelligentsia) have a bit of a sour taste as in the phrase гнилая интеллигенция (rotten intelligentsia). Members of intelligentsia class are viewed as prone to безволие (passivity), сомнения (doubts), and in general tend to spend too much time and effort on разговоры и дискуссии (in conversations and debates). Keep both connotations in mind when reading the passages about the Oldeners.

The other ones who survived the Blast are Перерожденцы or Degenerators. Who were they before the Blast is not entirely clear. One thing for sure – they are the opposite of the Oldeners in nearly everything, from their language to their life after the Blast to the remnants of the olden times they try to preserve (and how successful they get at it).

Yet the Oldeners and the Degenerators co-exist without giving much notice to each other, each serving their functions in the stale world of Fyodor-Kuzmichsk. And they’d go on like this forever, if not for the sinister cloaked Санитары or Saniturions dashing around in красные сани (red sleigh) picking up those afflicted by Болезнь (Disease). Who are they? What is their motive? And what is this mysterious, terrifying, unmentionable Disease that is neither a Consequence (everyone has Consequences) nor Freethinking?

Reading The Slynx, you might be reminded of A Canticle for Leibowitz (post apocalyptic loss of scientific knowledge), Clockwork Orange (use of argot as well as reading the Book without comprehending it), and Fahrenheit 451 (although it is more of a storyline perpendicular here). But I better stop or I’ll give out too much of the story.

Have you read The Slynx or other of Tatiana Tolstaya’s works? What do you think of The Slynx? Do you know Tatiana Tolstaya has a Живой Журнал (LiveJournal) blog where she, among other things, reviews books by contemporary Russian authors?

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Alexis:

That book sounds so interesting. Do you know if the English translation is good? I’m not sure my Russian is ready for it. 🙂

yelena:

Alexis, I thought that the English translation was very good. It is a difficult novel to translate because the characters speak in such a peculiar way. Plus many words (including Slynx) are made up, but are easy to understand nevertheless. There are a few instances when I thought that the translation had a deeper meaning than the original Russian, including Saniturions.

Nicolas:

elena. only the first four lines of your last 4 blogs have been sent to my e-mail account. there is some fault, i think.

yelena:

@Nicolas Nicolas, the IT changed the settings on all the Transparent blogs. With the new settings, if you subscribe by e-mail or RSS feed, you will only see the first few lines of a blog post (and no videos or images). It is inconvenient, but it was done because so many times a subscriber would read a blog post in an e-mail and hit the “Reply” button for comments. But the Reply would not go to the blog 🙁

Rob McGee:

Alexis — I would definitely recommend that non-Russians (and especially native English speakers) read the novel first in the English translation. That way you’ll be familiar with the plot, the characters, the bizarre mutant creatures, and most of all the “argot” before you attempt to read the Russian.

Just as an example: In the very first chapter of the novel (Chapter “Аз” — each chapter is named after the archaic names for the letters of the Cyrillic alphabet), you’ll find this sentence in Russian:

Клель – самое лучшее дерево.

The last three words aren’t difficult — “the very best tree” — but what the heck is a клель, which you won’t find in any Russian dictionary?! The English translation by Jamey Gambrell is as follows:

“[The] elfir is the best tree.”

Of course, there’s no such word as “elfir,” but an English speaker will immediatley recognize thatthat the word is a “portmanteau” of elm and fir. And similarly, клель is a combination of клён (“maple”) and ель (“spruce”). Apparently it’s some sort of mutated hybrid, because the text describes it as having шишки (“pinecones”) but also лапчатые листья (“paw-shaped leaves”), rather than needles.

Anyway, the full Russian text is available and downloadable for free online (at lib.ru/PROZA/TOLSTAYA/kys.txt), and even if you’re reading the English translation, it’s useful to have the Russian text for comparison.

yelena:

@Rob McGee Thank you, Rob! Once again, a thorough and insightful explanation. I agree – non-native speakers of Russian should probably start with an English translation first, even the advanced learners.

yelena:

@Rob McGee Rob, I didn’t even catch the “elfir” in the English translation. I totally read it as “elf”+”ir”, not sure why 🙂 And in my head it sounded like эльфир too until I read your comment! Awesome and thank you!