How the German Word “Fräulein” Disappeared Posted by Sten on Feb 18, 2021 in Culture, Language

Language moves and evolves, often along the lines of what a culture still deems acceptable or not. German is not immune to this, of course, and this week marked the 50th anniversary of the disappearance of a belittling word: Fräulein. A “little woman”. It disappeared in legal ways, at least. That doesn’t mean you won’t ever hear it anymore. What is a Fräulein, what was and is its meaning in German, and how was it banned?

What is a Fräulein?

A Fräulein is, literally translated, a “little woman”.

The word das Fräulein is quite obviously a derivative of the German word for woman: die Frau. Belittling of a word in German comes with the ending -chen or -lein. For example: das Mädchen (the girl) and das Fähnlein (the little flag). So that’s how Fräulein simply means “little woman”.

Interestingly, Frau comes from the althochdeutsch (Old High German) word frô, which means Herr (Mister, sir, lord), a very male word. So for a long time, linguistically, the Frau was like the extension of the man.

Into the Middle Ages, the Jungfrau (“young woman”, virgin) was simply a woman that wasn’t married (yet). Later, when Christianity really took hold, the element of Jungfräulichkeit (virginity) entered the mix, with Maria being the Jungfrau. So, the unmarried women were called by a different name: das Fräulein or die Jungfer, a derivative of Jungfrau.

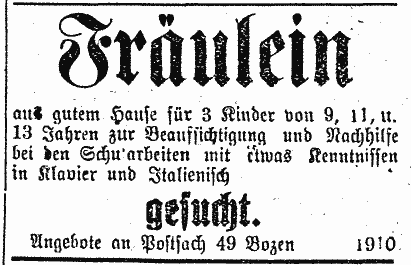

Initially, both Jungfrau and Fräulein were only used to refer to unmarried women of royal standing, like the word “damsel”. For example the daughter of a Fürst (monarch) was a Fräulein (also see Burgfräulein – a “castle lady”). Over time, the terms became more and more colloquial, to the point that Fräulein was bastardized to Frollein, and was used as a way to address a “Miss” around the late 19th to early 20th century.

Celibacy and bans – new meaning for the Fräulein

In the German Empire from 1880 to 1919, a so-called Lehrerinnenzölibat (female teacher celibacy) was in force. According to this, a female teacher was by law not allowed to be married. If she did get married while being teacher, this celibacy law called for the woman to get fired. In general, a Berufstätigkeit (professional occupation) for women was seen as a pre-marital thing. Once married, a woman was not deemed to be able to handle both a job and a family. Furthermore, women were seen as unnötige Konkurrenz auf dem Arbeitsmarkt (unnecessary competition on the job market). Interesting how a woman that couldn’t handle a family and a job is simultaneously a threat for men trying to get a job… If you want to learn more about the Lehrerinnenzölibat, look here.

Similar rules to connect the marital status of a woman to her employment existed in Germany until 1957. 1957! At that time, husbands lost their right to prohibit their wives of getting a job. So finally, Frauen could get a job without having to worry about their marital status. By law, that is.

The word Fräulein stuck, hartnäckig (stubbornly), as a way to address women at the workplace. For example in the supermarket, in a professional environment:

Fräulein Mack, kommen Sie bitte zur Fleischtheke?

(Miss Mack, could you please come to the meat counter?)

So even in a work setting, you could be called Fräulein.

But a big change to this came in 1972.

1972: The end of das Fräulein

Fräulein was next to the married Frau and the Herr (used for all adult men) used as a formal Anrede (address). Frau and Herr are already short, so they would not be abbreviated. Fräulein, on the other hand, was shortened to Frl.

While in 1955, Bundesinnenminister (Federal Minister of the Interior) Gerhard Schröder (CDU) already ordered that in amtlichen Schreiben (official letters) women were to be addressed as Frau, if they so wished, the general rule was still to address married women as Frau and unmarried women as Fräulein. As Schröder wrote:

„Die Bezeichnung ‚Frau‘ ist weder eine Personenstandsbezeichnung noch ein Teil des Namens noch ein Titel, der verliehen werden müßte oder könnte. Sie ist auch nicht gleichbedeutend mit ‚Ehefrau‘. Vielmehr steht es jeder unverheirateten weiblichen Person frei, sich ‚Frau‘ zu nennen. Von dieser Möglichkeit wird zunehmend Gebrauch gemacht. Es ist daher gerechtfertigt und geboten, unverheiratete weibliche Personen auch im amtlichen Verkehr mit ‚Frau‘ anzureden, wenn sie dies wünschen.“

(“The designation ‘Mrs’ is neither a civil status designation nor a part of the name, nor a title that should or could be conferred. Nor is it synonymous with ‘Wife’. Rather, every unmarried female person is free to call themselves ‘Mrs’. This option is increasingly being used. It is therefore justified and necessary to address unmarried female persons also in official dealings with “Mrs”, if they so wish.”)

So a Fräulein had to insist to be addressed as Frau. It took another 16 years before the option became mandatory. On February 16, 1971, it was announced that the use of the word Fräulein was no longer allowed for Bundesbehörden (Federal authorities):

„Es ist an der Zeit, im behördlichen Sprachgebrauch der Gleichstellung von Mann und Frau und dem zeitgemäßen Selbstverständnis der Frau von ihrer Stellung in der Gesellschaft Rechnung zu tragen. Somit ist es nicht länger angebracht, bei der Anrede weiblicher Erwachsener im behördlichen Sprachgebrauch anders zu verfahren, als es bei männlichen Erwachsenen seit jeher üblich ist. […] Im behördlichen Sprachgebrauch ist daher für jede weibliche Erwachsene die Anrede ‚Frau‘ zu verwenden.“

(“It is time to take account of equality between men and women and the contemporary self-image of women in terms of their position in society in official language. It is therefore no longer appropriate to address female adults differently than the way it has always been customary for male adults in official language. […] In official language, the salutation “Mrs” must therefore be used for every female adult.”)

Finally! So since then, the Anrede Herr/Frau (Sir/Mrs) was standardized in German, and the use of Fräulein in any official way or in relation to a marital status fell increasingly out of use.

Is Fräulein still used today?

If you still hear Fräulein today, it is often used to speak to younger women and mostly by older men or women. With the history about the word, however, you can imagine that it has a clear diminutive tone, so avoid using it. I don’t think anybody appreciates being called a “little woman”, especially in a professional capacity!

However, you may hear it now and then as a way to refer to a woman’s youth and attractiveness. German celebrity Iris Berben, for example, called it a “kleine private Freude, dass ich noch ein Fräulein bin” (“little private joy that I am still a Fräulein”) in 2012.

Have you heard or used the word Fräulein before? In what way? What do you think about the word, is it ok to still use it? I want to know, so please tell me in the comments below!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Russ Swift:

Lived in Germany (Bitburg) for five years, 89-95. Heard “fraulein” used all the time without any negative connotation whatsoever.

Richard Roan:

I was stationed in Kassel in 1953. Now at age 85 I am taking Deutsche Sprache and found it strange that Fraulein was no longer in use. Thank you for telling me. Richard Roan. Winston Salem, North Carolina USA

Sten:

@Richard Roan Interesting!

Yes, the word is definitely not used as much as it once was.

Allan Mahnke:

Fascinating! I was aware of the disappearance of the word, but did not know that any “official use” pronouncements were made. Thanks!

Connie wind-Avery:

Fascinating- and I wasn’t aware that the use of Fräulein is politically incorrect nowadays (although welcome) can I just ask: when calling a male waiter it is Herr Ober, a female waitress is meant to be Fräulein! – still in German textbooks in the UK – obviously outdated- can you enlighten me on current use, please. Danke im voraus

Sten:

@Connie wind-Avery Good question!

Even “Herr Ober” is getting “veraltet” (old). It is probably best to either just go with an “Entschuldigung!”, “Entschuldigen Sie!” or calling them by their name, if you know it “Entschuldigung, Herr/Frau Schwarz, könnten Sie uns bitte die Rechnung bringen?” (Excuse me, Mr/Mrs Schwarz, could you please bring us the bill?)

So the formal ways to say Herr/Frau is good, Damen/Herren less so. Because even “die Dame!” and “der Herr!” are becoming obsolete as ways to address somebody directly. Of course, the “meine Damen und Herren” as a “Ladies and Gentlemen” is still very common, normal and unproblematic.

In short, best simply use “Sie”, or use Herr/Frau instead, not Herr/Dame or Herr/Fräulein, then you should be fine.

Karen K Brees:

So, does that mean that an unmarried woman with a doctorate pre-WWII would have been addressed as Fraulein Doktor Schmidt?

Sten:

@Karen K Brees Yes, in fact!

It’s a good question, I started wondering myself. And I found some evidence for it.

Here’s a book from 1924, called “Fräulein Doktor”: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/45352/45352-h/45352-h.htm

Here’s an excerpt:

Es war erreicht!

»Fräulein Dr. med. Beate Haßler«, hieß es seit mehr als einem Jahr!

Die Studienzeit war vorüber….

I am not sure when this ended, but I assume it was a pretty rare phenomenon at the time, especially with the idea that women were unwanted competition on the job market.

You’d think that a book like this discusses marriage extensively, too – and it does!

“Da mischte sich zum erstenmal Frau Haßler ins Gespräch. »Warum nur so viel Aufregungen? Ich denke, daß du über kurz oder lang doch heiraten wirst!«

»Heiraten, ich, Mutter? Ich denk nicht daran; wenigstens vorläufig noch nicht. Dahin komme ich noch früh genug, wenn es einmal sein muß. Jetzt will ich noch lernen.«

»Aber dein ganzes Streben und Arbeiten wird dich niemals so beglücken können wie das Bewußtsein, einem geliebten Mann anzugehören! Ich habe bisher geschwiegen, um alles zu hören, was du dir in deinem Köpfchen zurechtgelegt hast. Aber auf das eine, woran Vater noch nicht gedacht hat, möchte ich dich noch aufmerksam machen: Du beraubst dich selbst der reinsten, heiligsten Freuden, die dir durch nichts ersetzt werden können, wenn du auf deinem abenteuerlichen Vorsatz beharrst.«

»Weißt du denn das so genau, du Liebe, Gute? Ich will gar nicht endgültig darauf verzichten, in einer Ehe glücklich zu werden. Wenn mir jemand begegnet, dem ich gut sein kann und der mich heiraten möchte, dann können wir immer noch darüber reden; und wer weiß, ob ich nicht gar schon an jemand denke? Jetzt aber will ich vor allem selbständig sein und mir einen Beruf schaffen, daß ich allen Möglichkeiten gegenüber gewappnet bin. Wenn ich nun alte Jungfer werde? Das ist doch auch nicht ausgeschlossen! Das Leben ist so ernst, die Zeiten sind so schwer, daß man nicht so in den Tag hineinleben kann.”

So the protagonist goes against the grain and tells people that she wants to study, go for her career, and at every turn she is told that she maybe should better get married instead.

This really reflects the either/or mentality: either you have a job and become an “alte Jungfer” (old virgin) or you get married, have a family and take care of it.

At one point, she is engaged and her fiancé forbids her to study, but she doesn’t care and goes to study anyway.

A really interesting read on these dynamics!

Pius Gross:

Yes, Fraulein should be acceptable