What is the Active Participle in Arabic? (II) Posted by Ibnulyemen اِبْنُ اليَمَن on Sep 4, 2017 in Arabic Language, Grammar

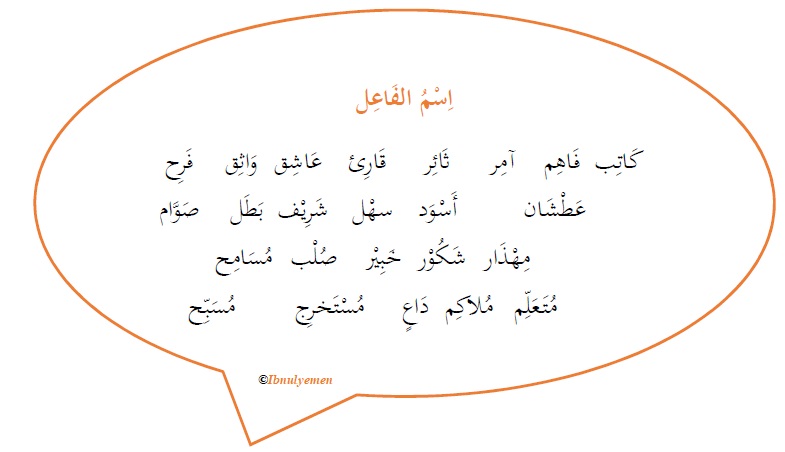

In the previous post, I explained what the active participle (AP) اِسمُ الفَاعِل means, when it functions as an adjective and when it is used as a noun, and how it is formed from active verbs. This post is about its derivation from intransitive verbs الأَفْعَال اللازِمَة and complex verbs الأَفْعَال المَزِيْدَة. Also, I will explain the exaggerative/repetitive form of AP صِيْغَةُ المُبَالَغَة, and how AP and its exaggerative form affect the parsing الإِعْرَاب of words that follow them.

Simple Intransitive Verbs and the Active Participle:

In the case of فَرِحَ and ضَخُمَ, which I cited in the previous post, we can see that the middle letter of the first has kasrah, while the second has DHammah. Also, they are both intransitive (i.e. they don’t need an object to form a meaningful sentence). For these reasons, deriving AP from them and other verbs with similar medial diacritical mark, take different forms, as in the table below.

اِسْمُ الفَاعِل |

الفِعْل المَاضِي |

حَزِنْ، حَزْنَان |

حَزِنَ |

فَرِحْ، فَرْحَان |

فَرِحَ |

شَبْعَان |

شَبِعَ |

عَطْشَان |

عَطِشَ |

رَوْيَان |

رَوِيَ |

أَكْحَل |

كَحِلَ |

أَحْمَر |

حَمِرَ |

صَعْب |

صَعُبَ |

سَهْل |

سَهُلَ |

كَبِيْر |

كَبُرَ |

جَمِيْل |

جَمُلَ |

Is there a rule for this? Yes, to some extent.

Concerning the verbs that belong to the same group as فَرِحَ with respect to the diacritics, If the verb expresses a casual happening/event, as in the verbs in blue in the table, the AP is the same in form as the verb, except for the final diacritical mark, which can be fatHah, DHammah, or kasarah or the corresponding tanween should the word be نَكِرَة nakirah ‘indefinite’.

If the verb refers to quantity, that is something or someone is full of or devoid of something, as in جَوِعَ ‘to be hungry’ and شَبِعَ ‘to be full’, the AP is formed by adding ان to the end of the verb. Also, the kasrah of the middle letter changes to sukoon, hence جَوِعَ and شَبِعَ become جَوْعَان and شَبْعَان.

If the verb indicates colors or appearances, as in حَمِرَ ‘to become red’ or عَوِرَ ‘to become blind’, the AP is derived by adding hamzah to the start of the verb as well by changing the internal diacritics, therefore حَمِرَ becomes أَحْمَر and عَوِرَ becomes أَعْوَر.

As to the verbs that belong to the same group as ضَخُمَ and كَبُرَ, that is the medial letter has DHammah, there are a few ways to derive the AP. However, the most common are: 1) using the same form of the verb except for the middle diacritical mark. It changes from DHammah to sukoon, thus ضَخُمَ becomes ضَخْم, and 2) adding ي after the second letter and changing the DHammah of the middle letter to kasrah, so كَبُرَ become كَبِيْر.

Complex Arabic Verbs and the Active Participle:

The complex Arabic verb الفِعْلُ المَزِيْد is the verb that includes one, two, or three letters-of-addition (هـ، ن، أ، و، ت، س، ل، ي، م) besides the three letters of root. Therefore, the complex verb can be رُبَاعِي ‘of four letters’, خُمَاسِي ‘of five letters’, or سُدَاسِي ‘of six letters.’ رُبَاعِي is verbs like سَامَحَ ‘to forgive’ and أَخْرَج ‘to direct a movie’; خُمَاسِي is verbs like اِنْتَقَلَ ‘to move’ and تَعَلَّمَ ‘to learn’; سُدَاسِي is verbs like اِسْتَخْرَجَ ‘to extract’ and اِسْتَمَرَّ ‘to continue’.

Derivation of the AP from these verbs is straightforward and regular. First, we conjugate these verbs with third person singular masculine in the present, hence the above verbs become يُسَامِح, يُخْرِج, يَنْتَقِل, يَتَعَلَّم, يَسْتَخْرِج, and يَسْتَمِرّ, respectively. When forming the AP, we drop the يـ of the present and replace it with مُ (م with DHammah) and adding kasrah to the letter that is before the final letter of the verb if it is not already there. So, the AP from these verbs are مُسَامِح – مُخْرِج – مُنْتَقِل – مُتَعَلِّم – مُسْتَخْرِج – مُسْتَمِرّ. Here are more examples:

اِسْمُ الفَاعِل |

الفِعْلُ المُضَارِع |

الفِعْل المَاضِي |

مُكْرِم |

يُكْرِم |

أَكْرَمَ |

مُخْبِر |

يُخْبِر |

أَخْبَرَ |

مُشَاهِد |

يُشَاهِد |

شَاهَدَ |

مُنْتَصِر |

يَنْتَصِر |

اِنْتَصَرَ |

مُتَكَلِّم |

يَتَكَلَّم |

تَكَلَّمَ |

مُتَعَاطِف |

يَتَعَاطَف |

تَعَاطَفَ |

مُسْتَعْلِم |

يَسْتَعْلِم |

اِسْتَعْلَمَ |

مُسْتَرِيْح |

يَسْتَرِيْح |

اِسْتَرَاحَ |

If the pre-final letter is ي as in يَسْتَرِيْح – مُسْتَرِيْح, the kasrah which is supposed to go with the ي moves to the letter before it. If the pre-final letter is ا as in اِخْتَارَ – يَخْتَار – مُخْتَار ‘to choose’, the kasrah is needless.

Exaggerative Form of AP:

As the name suggests, this type of AP indicates the repetition in doing an action. This is the only feature that distinguishes it from the regular AP. The exaggerative form of AP is derived only from simple verbs الأَفْعَالُ المُجَرَّدَة. There are not specific rules for its derivation; however, there are two common forms of it.

In verbs like شَرِبَ – كَذَبَ – سَرَقَ, two forms of AP can be derived: regular and exaggerative. The regular means that the actor/doer of the action did/does it only once, hence شَارِب – كَاذِب – سَارِق. The repetitive/exaggerative form mean that the actor/does has done/is doing the action repeatedly, so شَرَّاب – كَذَّاب – سَرَّاق.

Similarly, with verbs like صَبَرَ – شَكَرَ – حَقَدَ, two forms of can be derived. The regulars are صَابِر – شَاكِر – حَاقِد, and the action was/is done once. The exaggerative are صَبُوْر – شَكُوْر – حَقُوْد. Therefore, we say مُحَمَّد صَابِر ‘Mohammed is patient’ if he’s patient in one occasion; we say مُحَمَّد صَبُوْر ‘Mohammed is always patient’ when he is always patient or known for being patient.

Parsing and AP:

In terms of parsing إِعْرَاب, i.e. end of words diacritical marking, all forms of AP affect the words that follow them the same way the active verb does. That is, AP that are derived from intransitive verbs have subjects and assign nominative case مَرْفُوْع to them, while AP that are derived from transitive verbs have both subjects and objects and assign nominative case to the former and accusative case مَنْصُوْب to the later. This will be elaborated on in a future post.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

KHATEEB ZAHEER AHMED:

Hi, there

Will u pls help me in understanding how الأفعال المترادفة r used in d sentence, that is where v have put جاء and where v can use أتى

Secondly I think almost all verbs r used with صلة may b I’m wrong which verb is attached with a صلة

Like ذهب

ذهب إلى

ذهب عن

ذهب ب

ذهب فى

Each of these verbs give different meanings bcoz of d صلة

Similarly every or most of d verbs r supported by صلة being an ajami pls teach me d suitable صلة for each verb and their meaning

Explain me my problems in Arabic no problem

Yours in duaa

Khateeb Zaheer Ahmed

Ibnulyemen:

@KHATEEB ZAHEER AHMED Hi Khateeb,

as for الأفعال المترادفة, their usage is to a great measure similar to that of English and many other world languages. There may be verbs that are almost identical and thus can be used interchangeably. Bear in mind the following:

– some are more common than others, the former are used in informal daily communication, while the latter are used in more formal settings or written discourse.

– some are outdated and rarely used in everyday communication and sporadically in very formal written discourse.

– some can have more than one meaning so paying attention to what would be covey the meaning of a sentence is key.

– with respect to أتي and جاء, they certainly can be used interchangeably. the only difference is the degree of formality. جاء is less formal (and more conversational) than أتي.

As for the second question, this is a great question indeed. I have never asked this. the meaning of the verb may change drastically because of preposition that follows it. To illustrate, the the verbs you have listed would mean as follows:

ذهب إلى went to

ذهب عن left alone, let be (when you say أذهب عني, it means “leave me alone”

ذهب بـ ‘went by’ or ‘destroy’ or ‘win’

ذهب في ‘went in’ or ‘lost in’ or ‘follow’

for the most part, the context, i.e. the adjacent words, determine the exact meaning.

No, not necessarily! not all verbs are supposed by a preposition or صلة. this has to do with the verb is transitive or intransitive. The intransitive usually requires a preposition or a صلة, and when you say a صلة it means that the verb can not link directly with the object, rather through a preposition.

enjoy learning!

Khateeb zaheer Ahmed:

@Ibnulyemen Assalaamu alykm warahmatullaaahi wabarakyaatuhuu

May Allaaahu ta aaalaaa Bless u with all Khairs in both d worlds

Good presentation with regards to my queries

But pls bear with me in explaining me about verbs and their change in the meaning due to the entry of a صلة

with regards

Khateeb Zaheer Ahmed