Getting understood in Iceland: eight times G. Posted by hulda on Dec 4, 2013 in Icelandic grammar

Back to the pronunciation series! Speaking a new language is something that’ll grow on you little by little so don’t even think you’re supposed to learn this all in one go, but it may be helpful to read over and then go back to if/whenever something puzzles you. Something probably will, sooner or later, because the way Icelandic is spoken differs greatly from how it’s written. I sometimes wish Icelandic had more letters in the alphabet instead of just having, as the title says, eight ways of pronouncing one letter, G. If you think that’s bad just wait until we get to the letter N that has altogether nine different forms of pronunciation…

Back to the pronunciation series! Speaking a new language is something that’ll grow on you little by little so don’t even think you’re supposed to learn this all in one go, but it may be helpful to read over and then go back to if/whenever something puzzles you. Something probably will, sooner or later, because the way Icelandic is spoken differs greatly from how it’s written. I sometimes wish Icelandic had more letters in the alphabet instead of just having, as the title says, eight ways of pronouncing one letter, G. If you think that’s bad just wait until we get to the letter N that has altogether nine different forms of pronunciation…

G as [g]

Starting with the easiest of course, the G that’s pronounced like G. For some of you whose mother tongues include a soft G this may be slightly challenging: for a Japanese example, Icelandic G is not like the G in “arigatou”, it’s more like the K in “kokoro” or “hanako”. Examples: rigna (= to rain), gata (= a street), sorg (= sorrow). A G is always pronounced [g] unless any of the following exceptions is present.

G as [g:]

Easy one: long G is written with two Gs. Vagga (= a cradle/to rock, to sway), Sigga (= a nickname for a girl called Sigríður), skuggi (= a shadow) are all pronounced with a long G.

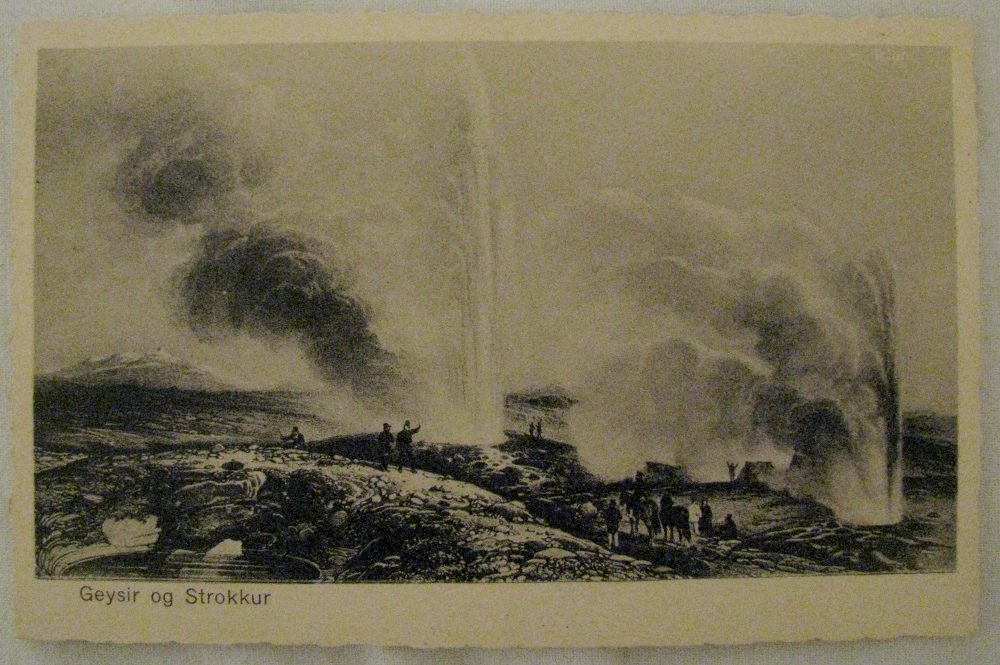

Geysir að gjósa (= Geysir erupting). Both Gs are pronounced as [gj].

G as [gj]

G gets an additional J in pronunciation whenever it’s followed by the vowels e, i, í, y, ý, æ, ei or ey or the consonant j. Examples: gæs (= goose, also used instead of hen for women right before their wedding), geyma (= to store, to preserve), lengi (= for long, for a long time), í gær (= yesterday) and gjöf (= a gift).

Exceptions to this rule include f.ex. foreign names, compound words and word that have the ending -endur, such as Bergen, bergeitill (= laccolith) and eigendur (= an owner)

But why do I claim that something written as GJ is just a form of pronouncing G instead of the two letters separately? It’s because they’re tied together into one sound when spoken. In some languages, for example Japanese and my native Finnish, the pronunciation for a word written with “gj” would be very different (if not borderline impossible). In fact even English-speaking language learners sometimes try to pronounce the letters separately, when in fact the J is tied to the G so much that it becomes more of a G than a J. F.ex. the word gjöf should come out of your mouth as one syllable, not as “gi-ööf”.

G as [gj:]

Another easy one – it’s an extension to the rule above and works when there are two Gs. F.ex. eggið (= the egg), leggja (= to lie down, to park, sometimes also to ice over) and beggja (= both, genitive form of the word báðir).

Vatnið lagði (= the lake froze), the G is pronounced as [ɣ]

Well, in truth this photo is from the Jökullsárlón below Vatnajökull, it’s always icy . 😉

G as [g]

When G comes after a vowel or is followed by a, u or a voiced consonant (link), it becomes a [g] instead. The same happens if G is the last letter of the word and there’s a vowel before it.

Vowels examples: eiga (= to own, to have to), stigi (= stage, degree, grade)(note that in this case G is indeed pronounced [g] instead of [gj]), þegar (= when, then, after).

Voiced consonant examples: sagði (= I/she/he said), vonbrigði (= disappointment), hægri (= right, the exact meaning is more “to the right”), bláeygður (= blue-eyed).

G ending a word with a vowel in front of it examples: ég (= I), stig (= stage, degree, level).

Note that sometimes a consonant that’s usually voiced may turn unvoiced by some other pronunciation rule. When this happens the G will follow suit and then these rules do not apply to it anymore.

Vel lagt lagt! (= A well-parked parking) The G in the word “lagt” is pronounced as [x].

G as [x]

[x] is formed in the back of your throat and is actually little more than a throaty breath. 😀 I mentioned earlier that Icelandic is not spoken as much as it’s whispered, a large part of the language coming out literally unvoiced! The rule of G becoming [x] is that is has to have a vowel in front and either T or S right after. Examples: sagt (= said, a declension form of the verb segja) and hugsa (= to think).

Note though that in spoken language a G that ends a word is often pronounced as [x] because it’s faster and easier than [g]. In the most extreme cases it may even be dropped off completely (even faster and easier than [x])!

G as [j:]

This one is going to be a little difficult to tell apart from the G as [gj] and the G as [g] -rules so it might be good to go read back on them and then compare. G turns into a [j:] (in English a similar sound would be f.ex. the Y in “you”) when it comes after a vowel and is followed by the consonant J or the vowel I.

Examples: segja (= to say), lagi (= form, as in “allt í góðu lagi” = everything ok/in great shape!), feginn (= happy).

G as [-], in other words an unvoiced G

If the G is between two of the vowels a, á, ó, u and ú it falls away completely! Examples: ljúga (= to lie), skógúr (= a forest). Note that words that end with G and would otherwise follow the G as [g] -rule BUT have one of these vowels before the G will also drop it off!

Well, that certainly was confusing, right? Not to worry. When figuring out a pronunciation of a word look at the sounds surrounding the G and try to find the correct rules by them. Listen to as much Icelandic as you can, repeat after or speak as much of it as possible – or sing, I’ve found that singing along my favourite Icelandic songs has helped me the most, pronunciation-wise – and the pronunciation rules will embed themselves in your brain on their own. This list of rules is helpful in the beginning but you’ll soon notice you won’t need it at all. 🙂

Here’s a funny little poem that suits the theme perfectly because it has so many different usages of the letter G. See if you can link together what pronunciation goes with what type of G and why!

Previous pronunciation posts:

Getting understood in Iceland part 1.

Getting understood in Iceland part 2.

Getting understood in Iceland: pre-aspiration.

Getting understood in Iceland: the difficult sounds, R, Þ, Ð and LL.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: hulda

Hi, I'm Hulda, originally Finnish but now living in the suburbs of Reykjavík. I'm here to help you in any way I can if you're considering learning Icelandic. Nice to meet you!

Comments:

Corin:

Hi Hulda,

I’ve been listening to útvarp saga a bit recently, and there are a few words that keep cropping up *a lot* that i am having difficulty translating by ear. To my english ears, something like….

1. “Sko” – is happens so often, at the beginning of sentences, it seems like its a particle similar to noch or doch – is it a pronounciation of “Svo” = (english: So,…)or does it mean something else entirely, like “look” as in the english “look here,…”

2. ég “atlar” is this ætlar, just with a very short “æ” or something about skipping or jumping?!!?

also in one of the adds there is a word like “jólpaka”? – is this “christmas present” or paka = a form of poka = christmas sack/s?

hope you are well, cheers corin

hulda:

@Corin Hæ hæ!

1. “Sko” is a fill-up word that people tack here and there. It has no real meaning in conversation, I’d go as far as to say that it’s used more as punctuation than a word. 😀 It can be translated but its meaning depends greatly on where and how it’s used: it can mean “so”, “look”, “like”, “like that”, “you know” etc.

“Sko” exists almost solely in spoken language and internet slang, but it’s so catchy you wouldn’t believe it! One of my professors once asked me to stop using it entirely (the complaint was that I’m picking up all too much slang, which is not proper Icelandic), as well as the word “bara”, another fill-up word for spoken Icelandic. Technically speaking “bara” means “only”, “just”, “just a little” etc. but the correct Icelandic word for that is “aðeins”. I think “bara” may be a Danish loan word at origin.

2. Most likely it’s “ég ætlar”, you’re right. Icelanders shorten the words brutally when they speak: endings get dropped, sounds change slightly to an easier form, words get tied together. One of my friends, when she was feeling a bit busy, pronounced “ég veit það ekki” as “éi-ggi”.

“Jólpakki” is indeed a Christmas present, but no wonder you heard “jólpakka” instead, the declension of the word “pakki” looks like this:

http://bin.arnastofnun.is/leit/?q=pakki

corin:

@hulda þakka þér fyrir,

In truth I suppose my english can be brutal too:

“I do not know” –> “I don’t know” –> I’dunno”

I can understand how that would seriously mess with a non English speaker. Of course they wouldn’t be listening so much for all those inflections!!!!

On a random note I got bored the other day and started taking a look at Russian. New, maddening, phonemes, a seperate instrumental case (utility not transferred into the dative)!! Truely spectacular de novo word generation through adjectival suffxing!! Insane (sic) use of verbs depending on the nature of motion!!

But Icelandic is where my heart lies….

hulda:

@corin English does have one thing going for it, its popularity! It’s easier to learn to listen to shortened language when examples are easy to find, just going to the movies trains the ear on how English works.

Oh dear, it seems that the gateway theory on language studies was correct! Once you start you can’t stop and in no time you’ll be thinking of picking up a new language – I’m sad to say this but you’re beyond salvation. You might as well dive into Russian as well, there’s no use fighting the temptation. 😀

Bragi:

Hi Hulda, flott grein hjá þér, takk 🙂

one comment though, you say that the G in lagt (vel lagt) sounds like a x, this is not true.

In this case the G sounds more similar to ch in Bach.

But when Icelanders say for instance, að hafa lagst niður, then the G sounds like x.

You see this also in your examples you make; sagt og hugsa, in the same paragraph, there the sound difference in very clear and not at all the same, as you say! the G in sagt would be like the ch in Bach, but the G in hugsa sounds like an x.

Also you say this:

“Note though that in spoken language a G that ends a word is often pronounced as [x]”

I can not think of any word ending with G that makes the x sound. Perhaps you mean at the end of a word, not that ends a word?

Annars bara allt í góðu og flott framtak 🙂

kær kveðja,

Bragi