Hacking Pronunciation in Any Language with the IPA, Part 3: Phonetics Posted by Transparent Language on Apr 1, 2015 in Archived Posts

Jakob Gibbons writes about language and travel on his blog Globalect. He often shares his experiences with learning languages on the road, and teaching and learning new speech sounds is his specialty.

In the first and second posts in this series on pronunciation, we delved into phonology and using the IPA for learning consonants and vowels in any new language. If you’ve been practicing, you should be ready for the third and most difficult part of pronunciation: phonetics.

In the first post on consonants we learned that, for example, the /p/ in the English word ‘pin’ is a voiceless bilabial plosive. But the same /p/, that very same voiceless bilabial plosive, is not the /p/ found in Spanish or Dutch or Hindi. In fact, a /p/ isn’t always the same /p/ even within any given language – can you tell the difference between the /p/ in English words ‘pin’ and ‘spin’? Probably not; their pronunciation is so natural as to be made effortlessly by native speakers, but the difference also contributes to that ‘almost perfect but not quite’ accent that many English learners have.

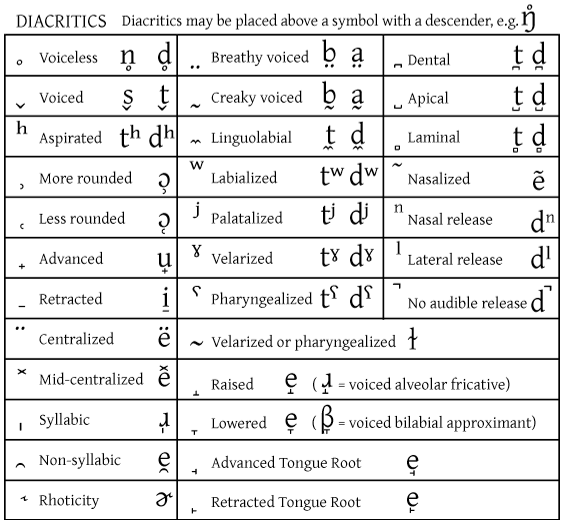

These most minute details of pronunciation are called phonetics, and they’re both the reason you have an accent in a foreign language and the trick to getting rid of that accent. And, just as with consonants and vowels, the IPA can help you train your tongue to execute flawless native-like pronunciation in any language.

Phonetics vs. Phonology

What we’ve talked about so far in this series is phonology, the system of phonemes or meaningful sounds in a language. In English, /p/ is a phoneme because the difference between it and other sounds yields the difference between pairs of different words like ‘pin’ and ‘bin’. However, the difference between the /p/ in ‘pin’ and that in ‘spin’ (we’ll get to just exactly what the difference is in a moment) is not phonemic because it’s never used to distinguish between different words.

These are phonetic differences, and they’re the most subtle details of pronunciation in any language. They’re the reason why, even after your 10 years living in Mexico, your todo doesn’t sound quite like the Mexican todo. You’re probably saying something like [`tho-do] or [`tho-ðo], while natives say [`to-ðo] without that little puff of air represented by the superscript h.

Using the IPA for Phonetics

Phonetics is not as neatly organized as phonology, and it’d be impossible to discuss it exhaustively in one short blog post. Instead, here’s a short sampling of the typical phonetic differences that give away even the most fluent of foreign language speakers as non-natives:

Aspiration: I’ve mentioned this one several times already because it’s probably the number one sign of an Anglophone in any language. English stops [p, b, t, d, k, g] often have a lot of aspiration, meaning a puff of breath from the throat following the release of the sound, but this is not necessarily normal in most world languages.

Hold your hand in front of your mouth and say the words ‘pin’ and ‘spin’ (be sure to say them naturally and don’t overemphasize any part of the words). You should feel a noticeable puff of air after the /p/ in ‘pin’, but not in ‘spin’. That first /p/ is aspirated, as are most word-initial stops in English, but the one that follows the /s/ is not.

If you can practice saying words like ‘pin’, ‘tab’, ‘kit’, and others that start with stops, but saying them without releasing their normal puff of aspiration, you’re on your way to a flawless accent in a language like Dutch that features little aspiration. Even more, many South Asian languages (like Hindi) make a phonemic distinction between aspirated and unaspirated sounds, so that [pal], a verb meaning ‘to take care of’, is different than the word [phal] with its aspirated /p/, meaning ‘knife blade’. Important distinction, I’d say.

Degree of rounding: If you listen to an American English speaker say ‘no’, and a native Spanish speaker say no in Spanish, the difference is easy to hear. There are two aspects to this difference: one is diphthongization (which can be talked about just using the regular IPA vowel chart), and the other is degree of rounding.

Essentially, the English /o/ is made with the lips a bit more open than its Spanish cousin, whose articulation requires the lips to form a tight, nearly perfect circle. So if you hear a tiny difference like this one with a rounded vowel like /o/ or /u/, but your IPA vowel chart says you’re using the right phoneme, try playing with the shape of your lips as you say it. You might find that a little more or less puckering was all you needed to cover up the little Union Jack that falls out of your mouth every time you answer in the negative in Spanish.

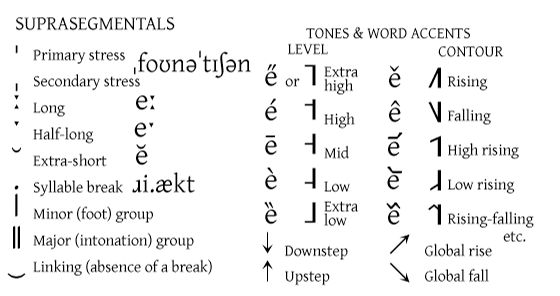

Prosody: Prosody is the rhythm of speech, where the stresses fall within words and sentences, and it is another phonetic aspect that often pulls the trigger on the non-native flare gun. Prosody at the word level is fairly easy to learn: most English learners wouldn’t say something like “I’m goING to the supermarket”, with the emphasis on the latter half of the word ‘going’, but they may not know where to place the stress within the suprasegment of the sentence, whether ‘going’ or ‘supermarket’ is getting the most vocal attention.

Even for phonetic details, prosody is tough to get down. It’s often one of the very last aspects of nonnative speech that remain to give away the speaker’s true identity, partly because it’s nearly impossible to practice in any structured or focused way. Look at phonetic spellings in the dictionary to figure out where to put the stress within a word, and look for their patterns (for instance, affixes and grammatical inflections normally aren’t stressed). For sentence prosody, try watching speeches or documentaries and repeating entire sentences exactly how you hear them, with an ear for which parts are receiving more or less stress.

Getting control of the proper consonants and vowels is the first step toward proper pronunciation in a foreign language. When learning English, it’s important to master the sound represented by the letters <th>, by putting your tongue between your teeth and squeezing air out. Escaping the trappings of your mother tongue and picking up the proper vowels of another language – like the notoriously difficult nasal vowels of French, or the series of sounds in Northern European languages that just sound like a flat /ǝ/ to English speakers – is the second step, after which you can be sure you’ll always be understood and probably even receive compliments on your pronunciation.

But once you’re in control of the basic sounds of your new language, if you want to reach all-star status, you’ve got one final step to go. Want to see that gratifying look of surprise on someone’s face when you say “oh, no, I’m actually not from here”? Then it’s all about phonetics.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: