How I Became Trilingual in Three Years (and How You Can Too) Posted by Jakob Gibbons on Jun 24, 2015 in Archived Posts

In 2012 I was your typical monolingual English-speaking American. Now, almost exactly three years after picking up my first Teach Yourself Dutch book, I’m a functional trilingual backpacking my way through Latin America. I didn’t do it through expensive courses or an auspicious blow to the head, but instead by learning about how the brain naturally acquires languages and using it to my advantage.

Earlier this year I wrote the Trilingual in Three Years series on my blog Globalect, and now I’m sharing here the method that I elaborated there. The basic psycholinguistic formula for language learning can be broken up into two parts: statistical learning and social learning. Putting the cherry on top with witty sarcasm and slang and graceful communication is the third.

Statistical learning: it’s child’s play

Everyone who knows a little bit about language learning knows that babies are little geniuses at it. They’re not really putting in that many focused study hours; they’re just born with a gift.

That gift is their sponge-like ultra-language-absorbant brains that soak up not only speech sounds but grammatical patterns, sentence structures, and associations between words and meanings at a rate that the most advanced adult language learner could never hope to compete with. Leave a baby in any random country for a year or two and, while you’d be a horribly neglectful parent and international criminal, that kid would learn the language.

It’s because the infant brain is hard-wired for statistical learning of patterns, especially linguistic patterns. Statistical learning means that you present the language learning centers of your brain with massive amounts of data – words, sounds, sentences, grammatical structures, social cues – until your brain has decided it has a large enough statistical sample to start making sense of it all and organizing it into rules.

The learner of English as a second language will — regardless of being taught or not — eventually realize (most likely subconsciously) that people just do not say she goed in the past tense in English. After weeks or months or years of exposure to sentences constructed in English, the learner will have thousands upon thousands of examples of she went stored up in their mental repository, but only maybe a couple erroneous instances of she goed. Eventually, the thousands of examples of she went become the clear winner over she goed. The speaker’s brain has used all this data to sort out a rule.

While it comes naturally for babies, your adult brain will need some more structure and encouragement. But fear not: there are plenty of ways to soak your head in statistical language data via listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Watching television and joining conversation clubs are just some of the more obvious ones, but you probably haven’t thought of things like eavesdropping on conversations or reading Wikitravel pages in other languages. For actionable strategies like these, check out the full article on Globalect on Learning Language Like a Baby.

Social learning: it takes a village

The second foundation of language learning is using language for its intended purpose: interacting with other humans. It’s the more important and more enjoyable half of the language learning equation, and ideally you should do it from the beginning, even while you’re busy running all those statistics.

If statistical learning is about compiling and organizing language data, social learning is about putting it to use and learning through doing. Even despite their linguistic genius, babies will never become proficient in a language without social interaction, which means you won’t either. In other words: use it or lose it!

Once a baby has spent around a year devouring linguistic data from their environment, they start to associate mama with the woman who miraculously disappears and reappears during suspenseful rounds of peek-a-boo. Likewise, milk isn’t just a meaningless noise: it’s somehow tied to making that gnawing hungry feeling go away. These realizations are significant because the child can then use it to say milk to mama and accomplish a social task. This is what language is all about.

What this all means is that you need to form meaningful social relationships in your target language, just like babies do, to truly master it and assign useable meaning to your masses of linguistic data.

In the 21st century with its World Wide Web and cheap travel opportunities, there is no shortage of opportunities to socialize in a new language. Check out websites like conversationexchange.com, go to a Couchsurfing or expat meetup, or spend a summer backpacking or volunteering on a farm in a country where your target language is spoken.

Just be sure that you’re going beyond ritual practice and forming real social bonds, making new friends and learning about cultures as you go. I’ve shared plenty about how you can do all this, along with a whole list of other practical tips, in Globalect’s original post on Social Language Learning.

Bonus round: talking like a native

If you’re a vane language learner like most of us, you probably live for those “oh I didn’t realize you were foreign” moments. While the language professional in me wants to caution you that it’s silly to focus on superfluous things like accent or passing for native, the language learner in me knows it’s just really really cool when you can.

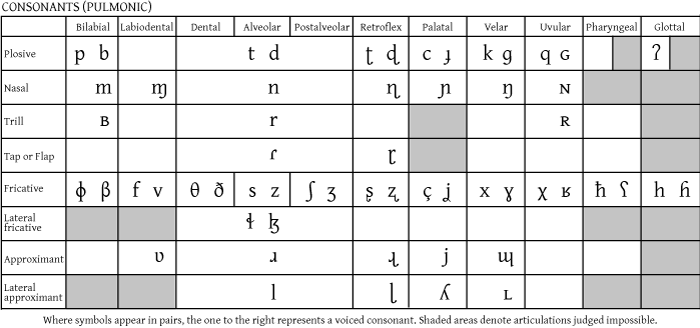

If you want to take the more scientific route to superficial perfection, you should follow the earlier series I wrote here on Transparent Language on ‘Hacking Pronunciation in any Language with the IPA’ (Parts 1, 2, and 3.) The International Phonetic Alphabet is the systematic transcription of every speech sound in human language, and learning it empowers you to recognize new sounds in other languages, measure the difference between your target sound and the one that’s currently giving you that accent, and with enough practice, close that gap.

I’m a big fan of the IPA for learning pronunciation, but I’m an even bigger fan of the social approach, in which immitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Keep soaking your statistics-hungry brain in social data: engage in conversations with people. When you can’t find someone to chat with, watch television. And imitate. Try to sound how the native speaker sounds. Listen actively, closely – they sound different than you, but why? Strive to put your finger on it and use the IPA to help you.

For the IPA method, check out my earlier series on Transparent Language linked above. For more practicable tips on how to get the ultimate compliment, being mistaken for native, take a look at my original post on Globalect: Talking Like a Native.

In just three years’ time I’ve gone from monolingual to polyglot-in-progress. I didn’t dump out thousands of dollars or get bitten by a radioactive spider, but instead I just learned how to learn. Now, three years later, I’m a totally confident and expressive speaker of English and Dutch, and my fluent Spanish is inching closer and closer to social grace and (hopefully) being mistaken for native every day.

To read my followup on three years of language learning using this method and how I’ve used it to learn Spanish while backpacking in Latin America, check out my latest post on Globalect: Trilingual in Three Years: Three Years Later.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: