Bringing Indigenous and Endangered Languages Online with Local Content Posted by Jakob Gibbons on Nov 14, 2016 in Archived Posts

The world is going global, and with it so are languages. The effects of globalization on the world’s linguistic diversity are a concern not only for those who want to preserve our human heritage, but also for ensuring equitable, sustainable development in the world’s poorest (and often most linguistically diverse) regions.

Imagine tomorrow you, your family, and your entire community are shifted into an alternate reality where everything is in a foreign language. From university courses to voter registration forms to services at the public library, everything is written in a language you can’t speak or read. Newspapers and public health messages are printed in meaningless letters, and TV stations and mobile service providers communicate in a language that might as well be static to your ears, created by bureaus in a far-away place that knows nothing about you or life in your local community.

Half of the Earth’s population, who don’t speak one of the dozen or so languages that dominate the Internet and its content, is in many ways living in this reality. The language you speak largely shapes your experience of the Internet, and in the wired world of the 21st century it has enormous repercussions for your access to healthcare, education, and participation in society.

Last month I mentioned how motivated language learners, dedicated public and civil sector organizations, and cutting edge technology can help us bridge the digital language divide and bring economically and linguistically marginalized communities online and into the 21st century knowledge economy. One of the biggest factors keeping many of the world’s developing and indigenous communities on the margins is this divide, the lack of access to relevant and useable content in the languages spoken by those who stand to benefit from it most.

But the answer isn’t as simple or as top-down as just teaching the rest of the world English and a few other dominant world languages. Actually, the first step is empowering local communities around the globe to become producers of content and knowledge in their own cultural and linguistic milieus, reengineering the web from the bottom up.

More Content in Local Languages Leads to More Internet Engagement

Experts from across the developing world are building a consensus on bridging the divide, and it starts with personal, societal, economic, and technological investment in minority and indigenous languages. According to UNESCO,

“Increasingly, information and knowledge are key determinants of wealth creation, social transformation and human development. Language is a primary vector for communicating information and knowledge, thus the opportunity to use one’s language on the Internet will determine the extent to which one can participate in emerging knowledge societies.”

A 2015 report from the World Economic Forum outlined 3 figures that explain the digital divide, pointing out that, despite unprecedented availability of cheap mobile internet across even the world’s poorest regions, only about a third of the global population has sprung for a mobile internet subscription. So if access and affordability aren’t the primary roadblocks, what is? According to WEF, relevance matters most:

“Is there content available in the local language? Is it of interest? Is it useful? If the answer to these questions is no, then chances are many who could afford internet access will spend their time and money elsewhere.”

One of WEF’s conclusions is that of the growing consensus: we need more web content produced locally and in local languages.

Indigenous communities and those on the linguistic margins of society must be empowered to produce their own culturally and locally relevant knowledge and disseminate it online, in order not only to promote literacy and writing but also to increase the social prestige of traditionally undervalued languages.

Massive translation projects, whether they’re carried out by human translators or machines, fail to address one of the fundamental problems of the digital language divide: knowledge is culturally attuned.

A Russian meteorology textbook could of course be translated into Amharic, but the weather concerns of an industrialized country dominated by tundra and temperate plains will have little overlap with those of a largely agrarian society in the tropics. This is why, as UNESCO points out, “Speakers of non-dominant languages need to be able to express themselves in culturally meaningful ways, create their own cultural content in local languages and share through cyberspace.”

As I mentioned last month, nearly half a billion people on the African continent who have access to mobile data networks and reasonably affordable phones don’t go online. The biggest reason? According to the GSMA report on Consumer Barriers to Mobile Internet Adoption in Africa, “lack of locally relevant content” is one of the top roadblocks in most countries, with over 50% of respondents in linguistically megadiverse Nigeria and South Africa citing this as the reason for their Internet apathy.

In Nigeria, one of Africa’s largest and fastest growing economies, gains in human development are unevenly distributed between English speakers and Nigerians who speak one of the country’s more than 500 other languages. This is exacerbated by education policies that favor English above local indigenous languages, making the colonially inherited official national language the only practical pathway to reaping the benefits of advances in public health and economic opportunity that have come to the country in recent years.

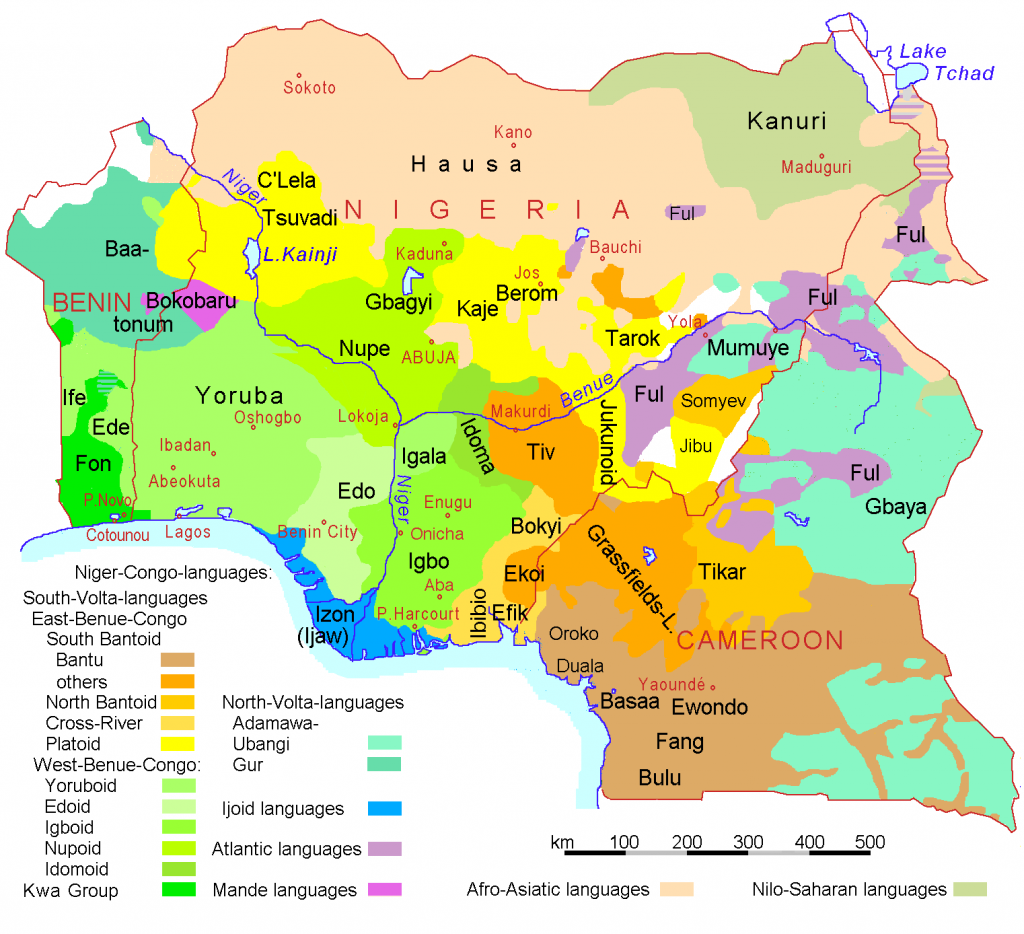

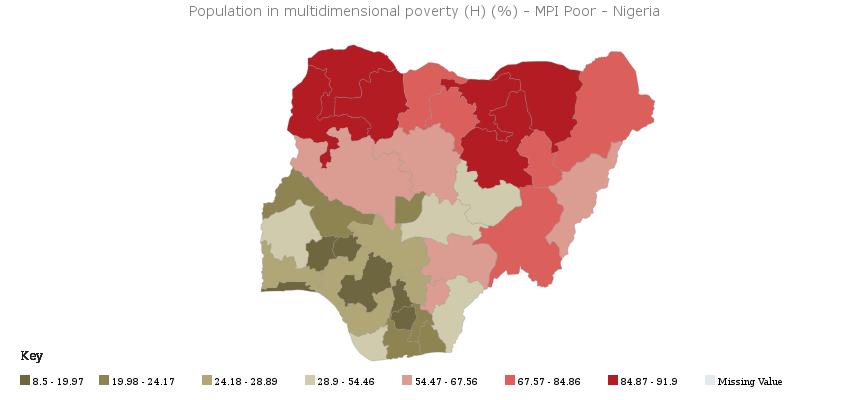

While there are certainly other issues exacerbating Nigeria’s development challenges, the digital language divide is undeniable there. The southern coastal areas are heavily urbanized and home to more English speakers than the poorer northern inland areas, where the majority of people speak languages like Hausa, Ful, and Kanuri at home and with other members of their community.

In the Hausa-speaking northern states, information is a scarce commodity. Far from the capital and the urban centers of the south, Hausa-speaking Nigerians have very little chance of casually bumping into someone who passes on the latest information on free vaccinations or the big political issues being debated in English in Abuja.

But despite the availability of mobile data networks and relatively affordable mobile phones, northern Nigerians have equally little chance of casually bumping into useful information online. There are only 1400 articles available in Hausa on Wikipedia, maintained by a mere fifteen active Wikipedians. Compare that to the 31,000 articles available to Yoruba-speaking people in the southwest, or the 5,280,000 English Wikipedia articles that are written and edited by a community of nearly 125,000 active users and available to educated, urban-dwelling Nigerians.

Wikipedia is but one small barometer for judging people’s opportunities to consume and create content and information online in their own language, but it’s no coincidence that these numbers line up unsettlingly well with a regional map of multidimensional poverty (which takes into account not only annual income but access to resources like healthcare and education).

As these geographic gaps in opportunity and development make their way into the digital world, how do we keep them from building linguistic walls across the Internet and keeping linguistically marginalized communities on the economic and social margins as well?

There’s a large body of evidence suggesting that increasing the availability of digital content in Arabic is a key to unlocking sustainable development in North Africa and the Middle East, a region where urban youths and the highly educated access the Internet in French and English while their rural and poorer neighbors have few options to do so. Throughout sub-Saharan Africa and India, studies have shown that increasing the availability of services like Facebook and Wikipedia in local languages has the potential to increase the number of Internet users in these regions by as much as 24%.

What would happen if a quarter of India’s population–some 400 million people, more than the entire United States–started using just Facebook and Wikipedia? How would it affect public health and economic opportunity if marginalized communities could be reached with messaging about vaccinations or school enrollment? What would happen if 75 million Telugu speakers in the south of India started writing, publishing, sharing, refining, and expanding upon each other’s knowledge and expertise on the world’s largest encyclopedia?

There’s every reason to believe that the impacts would be of a scale for the history books.

To learn more about initiatives to promote online content in local, indigenous, and endangered languages, take a look at 7000 Languages and some of the organizations they partner with across the world. To put your passion for languages to work bridging the digital language divide, start learning an indigenous or endangered language today.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: