Horae: Counting the Roman Hours Posted by Brittany Britanniae on Nov 30, 2016 in Latin Language, Roman culture

Salvete Omnes! I hope everyone has been well! Right now, everyone everywhere might be noticing the changing times of night and day. The beginning of Winter is coming and with that means the nights are getting longer and the days are getting shorter. Let’s see how the Romans dealt with this phenomenon.

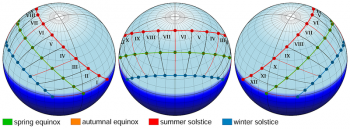

The paths of the sun on the sky during equinoxes and solstices AD 8 at Forum Romanum 41.892426°N 12.485167°E, horizontal coordinate system. The numbers indicate Roman horae (hora prima, secunda, tertia etc.). Courtesy of Darekk2 and Wikimedia Commons

For us, we keep track of the hours down to the smallest millisecond using our modern clocks. Our idea of how time passes is that it is constant and unchanging. We have even managed to use atomic vibrations to make our clocks as accurate as possible. The Romans, however, perceived time very differently.

We have inherited from the Romans the idea that there are 24 hours in a day. The Romans always insisted that there be 12 hours for both night and day. This meant that as the lengths of nights and days shortened or lengthened throughout the year the hours of the night and day would shorten and lengthen in accordance. Click the image below to see an animation of how the hours fluctuated.

Distribution of horae and vigiliae for the year AD 8 – GIF animation.

The surise and sunset times for this diagram are calculated for Forum Romanum 41.892426°N 12.485167°E AD 8 (the Julian calendar). Sunrise and sunset times are used as boundaries of day and night. Many sources however are ambiguous because of confusing terms sunrise with dusk and sunset with dawn. This is important, because times of dusk and dawn differ significantly from times of sunrise and sunset. The semidiameter of the sun and atmospheric refraction are taken into account. Equinoxes and solstices are computed too, not set by Romans.

Courtesy of Darekk2 and Wikimedia Commons.

The hours for the Romans were named in a very uniform manner, these names were the same for both the dya and night hours:

I hora prima

II hora secunda

III hora tertia

IV hora quarta

V hora quinta

VI hora sexta

VII hora septima

VIII hora octava

IX hora nona

X hora decima

XI hora undecima

XII hora duodecima

To distinguish between the day and night hours they would use expressions like: prima diei hora, prima noctis hora, hora prima noctis.

Romans generally had many markers throughout the day including: media noctis inclinatio “midnight,” gallicinium “cock-crow”, conticinium (with variants such as conticuum) “hush of the night,” and diluculum, “decline of the day.”

The Romans throughout the Empire considered the start of the day at different times. Some said the start was dawn, other claimed it was at was in later midnight. The modern English word “noon” is derived from the ninth hour “nona”.

In this excerpt we see that, to the author, the day began after the hour we might recognize as “midnight”, this would be the sixth hour of the night or “Hora sexta noctis”:

“Quemnam esse natalem diem M. Varro dicat, qui ante noctis horam sextam postve eam nati sunt” (Aulus Gellius: Noctis Atticae 3.2)

Which was the birthday, according to Marcus Varro, of those born before the sixth hour of the night, or after it

Interestingly, here is an excerpt of Ammianus Marcellinus describing the need for a leap year and is very informative of how Romans perceived the progress of time in a year:

Sed anni intervallum verissimum memoratis diebus et horis sex usque ad meridiem concluditur plenam, annique sequentis erit post horam sextam initium porrectum ad vesperam. Tertius a prima vigilia sumens exordium ad horam noctis extenditur sextam. Quartus a medio noctis ad usque claram trahitur lucem. Ne igitur haec conputatio variantibus annorum principiis et quodam post horam sextam diei, alio post sextam excursa nocturnam, scientiam omnem squalida diversitate confundat et autumnalis mensis inveniatur quandoque vernalis, placuit senas illas horas, quae quadriennio viginti colliguntur atque quattuor, in unius diei noctisque adiectae transire mensuram. (Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae, 26.1.9-10)

But the true length of a year ends, in the said 365 days and six hours, at high noon, and the first day of the next year will extend from the end of the sixth hour to evening. The third year begins with the first watch and ends with the sixth hour of the night. The fourth goes on from midnight until broad daylight. Therefore, in order that this computation because of the variations in the beginning of the year (since one year commences after the sixth hour of the day and another after the sixth hour of the night) may not confuse all science by a disorderly diversity, and an autumnal month may not sometimes be found to be in the spring, it was decided to combine those series of six hours, which in four years amounted to twenty-four, into one day and an added night.

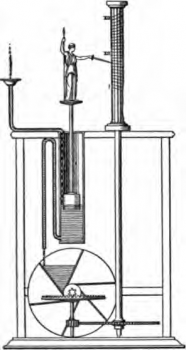

Diagram of a fancy clepsydra. Water enters and raises the figure, which points at the current hour for the day. Spillover water operates a series of gears that rotates a cylinder so that hour lengths are appropriate for today’s date. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

We have seen the sundail as a part of Roman timekeeping, but they also used water clocks known as clepsydra. These clocks were called “water thieves” because they required water to run, but also because their use in the court system where testimonies would be given in accordance with the timing of a clepsydra which seemed to steal the time away. In much of this same sentiment, when sundails were introduced to Rome there were some that weren’t very happy with the sudden attention to the passing time. Take a look at this excerpt, Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 3.3.5:

ut illum di perdant, primus qui horas repperit,

quique adeo primus statuit hic solarium!

qui mihi conminuit misero articulatim diem.

Nam me puero venter erat solarium

multo omnium istorum optimum et verissimum:

ubi is te monebat, esses, nisi cum nihil erat.

Nunc etiam quod est, non estur, nisi soli libet;

itaque adeo iam oppletum oppidum est solariis,

maior pars populi aridi reptant fame.

The gods confound the man who first found out

How to distinguish hours! Confound him, too,

Who in this place set up a sundial

To cut and hack my days so wretchedly

Into small portions! When I was a boy,

My belly was my only sun-dial, one more sure,

Truer, and more exact than any of them.

This dial told me when ’twas proper time

To go to dinner, when I had aught to eat;

But nowadays, why even when I have,

I can’t fall to unless the sun gives leave.

The town’s so full of these confounded dials

The greatest part of the inhabitants,

Shrunk up with hunger, crawl along the streets.

The Romans counted their hours and monitored them. They bequeathed numbers and names of hours, but we have taken their counting and intensified it. With our atomic clocks and minute-counting there may be a few of us who relate to this today.

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

About the Author: Brittany Britanniae

Hello There! Please feel free to ask me anything about Latin Grammar, Syntax, or the Ancient World.

Comments:

George:

The four Evangelists wrote in Greek. Did they use Roman timekeeping or Hebrew timekeeping in specifying times? It is not clear from the text.