How to say ‘rat’ in Irish and a continuation of the glossary for ‘An Píobaire Breac’ (an t-aistriúchán le Seán Ó Dúrois (Cuid 4/4) Posted by róislín on Oct 7, 2017 in Irish Language

(le Róislín)

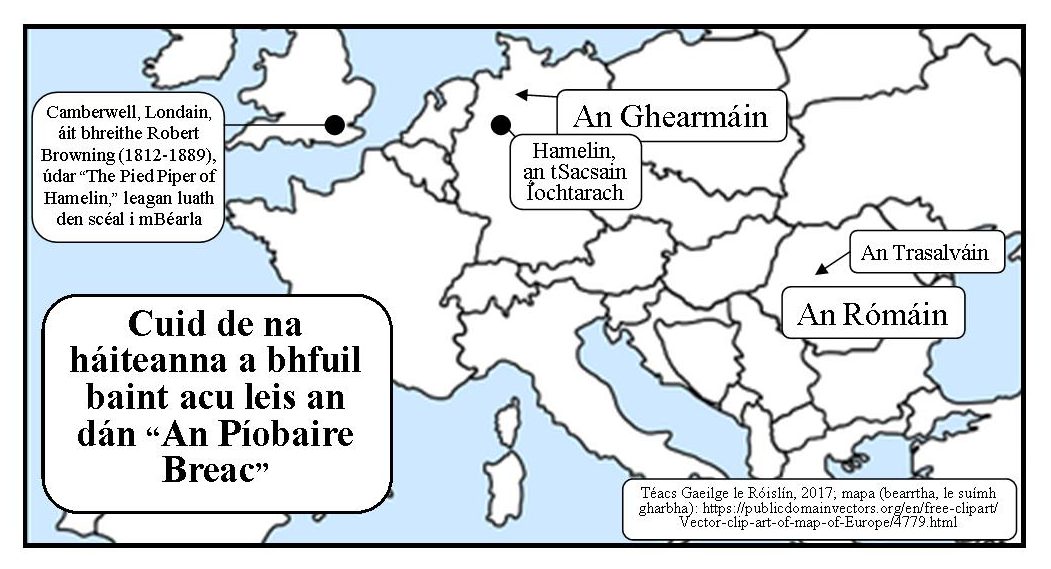

Seo an chuid dheireanach den ghluais don dán “An Píobaire Breac” (The Pied Piper) a tosaíodh cúpla seachtain ó shin (naisc thíos). Tá súil agam go raibh seans agaibh an t-aistriúchán le Seán Ó Dúrois a fháil (eolas foilseacháin thíos) agus é a léamh. Nó b’fhéidir é a úsáid i rang. Dála an scéil, baineann na huimhreacha “stanza” anseo leis an leagan Gaeilge, ní leis an leagan Béarla (tá difríochtaí ann). Leis an fhírinne a dhéanamh, níor clóbhualadh an leagan Gaeilge le huimhreacha ar bith, ach chuir mé leis iad do na blagmhíreanna seo. Freisin, tá logainmneacha sa leagan Béarla nach bhfuil sa leagan Gaeilge (Asia, Tartary, Koppelberg Hill, Brunswick) agus tá cúpla logainm sa leagan Gaeilge nach bhfuil sa leagan Béarla (an Íoslainn, Ljubljana/Liúibleána). Saoirse an fhile (nó an aistritheora), is dócha.

Since the title of this post still mentions rats, as covered earlier in this mionsraith, here’s a quick review of terms for “rat” in Irish: francach, luch mhór, luch fhrancach, and luchóg mhór. For more on these, please see the previous blogposts (naisc thíos, mar a dúradh thuas) .

Anyway, here’s the “gluais“:

Stanza 15: Hurá, not too surprisingly, means “Hurrah!” or “Hurray!” Another word with a similar meaning is “Abú!” (“Hurray for … !” “Hurrah …!” “Up with …!” or “… forever!”) but this one always has the name of the person, place, or organization being cheered in front of it, as in “Albain abú!” or the well-known song by Michael Joseph McCann (1824-1833), “O’Donnell Aboo!” (sometimes also written as “O’Donnell Abú!” even though the lyrics are in English).

Stanza 15: go dtí, often learned first as “to” (as in “go dtí an Spáinn,” to Spain), but it can also mean “until,” as in “… go dtí gur chuimhnigh sé go tobann ar an airgead.”)

Stanza 16: There’s quite a difference in his pay (a phá), if he gets the agreed-upon price, míle bonn óir (1000 gold coins) as compared to what the deceitful mayor is willing to pay in the end, caoga bonn óir (50 gold coins). Ironically, the Piper had only asked for “dhá chéad bonn (óir)” (200 (gold) coins) initially, not a thousand).

Stanza 17: Two words I’ve heard mostly in the Donegal dialect, “fosta” meaning “also” (the more widely learned word is “freisin“) and “crosta,” meaning “cross” (or: bad-tempered, peevish, fractious, and less related to our immediate context: cryptic, taboo).

Stanza 18: ina staic, used with the verb “to leave” (fágáil), rooted to the spot, essentially, I would say, like a stake, i.e. stock still.

Stanza 18: cluain, deceit, beguilement; completely different from another “cluain,” which means “meadow” or “pasture,” as in “Cluain Ard” (Clonard) or “Cluain Meala” (Clonmel)

Stanza 19: rúid, charge, rush, as in “Tháinig siad de rúid”

Stanza 19: shlog, swallowed, as in “Shlog sé a n-iníonacha agus a mic.” Remember, “sé” here refers to “an tollán i lár an chnoic.” And also remember, re: pronunciation, the initial “s” is now silent. So “shlog” joins the relatively small number of words, globally speaking, that start with an “hl” sounds, most of the rest of which that I can find are either Slavic (like Czech “hlad” for “hunger” or “hlas” for “voice”) or Old Norse (Hlidskjalf, the seat of Odin), with an occasional foray into Swazi (e.g. the place name “Hlatikulu“). A few examples of this sound in Irish, all with the silent “s” are “a shlabhra” (his chain), “a shloinne” (his surname), and “a shluasaid” (his shovel). And then, just for fun, let me point out this acronym, but I really haven’t got a clue how to pronounce it, whether it should be like a word (as we do with “NATO”) or as individual letters (as we do with “FBI”): HLOLARAWCHAWMP (Hysterically Laughing Out Loud and Rolling Around While Clapping Hands and Wetting My Pants).

Stanza 20: mar, here used for “where,” though, as a separate word, it can also mean “because” or “as.” Seo sampla ón dán: mar a mbíonn an ghrian ag soilsiú gach aon lá (where the sun shines every single day) — curious because this “tír gheal na n-iontas” is actually inside a hill, but then maybe there could be artificial underground suns. Or maybe it’s the “gile” (brightness) at the end of the tunnel.

Stanza 21: bhric (foirm den fhocail “breac”). “Rabhadh! Rabhadh! (mar a déarfadh an Róbat sa chlár teilifíse Lost in Space) … Aidiacht sa Tuiseal Ginideach!” Often one of the last grammatical features of Irish to be taught (Ceachtanna 68-69 as 72 sa leabhar Progress in Irish, mar shampla), adjectives can change when used in a possessive phrase, like “the hat of the small boy” (hata an bhuachalla bhig) or “the hat of the small woman” (hata na mná bige), where “beag” (small) changes to “bhig” or “bige” respectively. In stanza 21 of the poem, we have “bhric,” the “tuiseal ginideach, firinscneach” for “breac.” Remember, the “bh” is pronounced like a “v” here. The full phrase is “Sráid an Phíobaire Bhric” (The Street of the Pied Piper, or, as it would probably be called, “Pied Piper Street”).

Stanza 21: an Trasalváin. Hmm, from pipers to vampire territory! The poem concludes that the Piper had led the children to Transylvania (an Trasalváin). So did they become vaimpirí? At any rate, that sounds like a good topic to explore for some future blogposts, especially considering that Bram Stoker was Irish!

Stanza 22: de réir do bhriathair. Most of us learn the word “briathar” as “verb,” as in “briathra neamhrialta” (irregular verbs). But it can also mean “word,” as in this phrase “de réir do bhriathair” (according to your word). Similarly, there is the phrase “Dar mo bhriathar!” (My word!)

Bhuel, sin sin don ghluais agus tá súil agam gur spreag sé thú le “An Píobaire Breac” a léamh. Tá a lán dánta deasa suimiúla greannmhara eile sa leabhar. Is fiú mór é a fháil. SGF — Róislín

Naisc

How to say ‘rat’ in Irish and a preliminary glossary for reading ‘An Píobaire Breac’ (an t-aistriúchán le Seán Ó Dúrois) (Cuid 1 as 3)Posted by róislín on Sep 23, 2017 in Irish Language

How to say ‘rat’ in Irish and a continuation of the glossary for ‘An Píobaire Breac’ (an t-aistriúchán le Seán Ó Dúrois) (Cuid 2)Posted by róislín on Sep 25, 2017 in Irish Language

How to say ‘rat’ in Irish and a continuation of the glossary for ‘An Píobaire Breac’ (an t-aistriúchán le Seán Ó Dúrois) (Cuid 3)Posted by róislín on Sep 30, 2017 in Irish Language

Whose beret? Bairéad an fhrancaigh nó bairéad an Fhrancaigh? Nó bairéad an phúdail? (Showing possession in Irish)Posted by róislín on Sep 28, 2017 in Irish Language

Eolas foilseacháin: Ó Dúrois, Seán. An Píobaire Breac agus dánta eile do pháistí. Binn Éadair, Baile Átha Cliath, 2004. Gan ISBN sa chóip atá agamsa. I measc áiteanna eile tá an leabhar ar fáil ó https://www.cic.ie/books/published-books/an-piobaire-breac-danta-eile-do-phaisti-leabhair-cloite agus https://www.litriocht.com/product/an-piobaire-breac-agus-danta-eile-do-phaisti/ agus http://www.coisceim.ie/2004.html

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Leave a comment: