Hacking Pronunciation in Any Language with the IPA, Part 2: Vowels Posted by Transparent Language on Mar 2, 2015 in Archived Posts

Jakob Gibbons writes about language and travel on his blog Globalect. He often shares his experiences with learning languages on the road, and teaching and learning new speech sounds is his specialty.

Learning words and how to put them into sentences is certainly the first step in learning a new language. But once you’re ready to say those sentences out loud, those endless hours of vocabulary and grammar drills aren’t going to get you very far if no one can understand what you’re saying. Pronunciation is too often the highest hurdle for the aspiring language learner, even though it doesn’t need to be.

In my last post for Transparent Language, I wrote about using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) to crack the consonant code in a new language. In this post, we’ll use the same tool to navigate the infinitely more frustrating and confounding group of speech sounds: vowels.

Vowels matter.

While I’m traveling I meet people of all different language backgrounds, and a few conversations seem to repeat themselves in nearly every country. One of the most tiresome is one I often have in English with Romance language speakers, and it always goes something like this:

Spanish/French/Italian guy: Ahh, so you’re traveling through [country name]? What kind of places will you visit? Big cities? Mountains? Forest?

Me: Well I really love beaches. I grew up in Florida and I just really appreciate a good beach.

Spanish/French/Italian guy: OOOH-HO-HO, yes yes, we aaallll love a good beach, my friend! *wink, elbow nudge*

This is because, to my Mediterranean friend, the words ‘beach’ and ‘bitch’ often sound identical. Spanish, Italian, and French all lack the distinction between the tense vowel /i/ in ‘beach’ and the lax vowel /ɪ/ in ‘bitch’, leaving me forcing an overly-toothy fake smile and chuckling at a word joke that I’ve heard a thousand times (and is also not really a word joke, or any kind of joke).

Finding (and pronouncing) a good beach

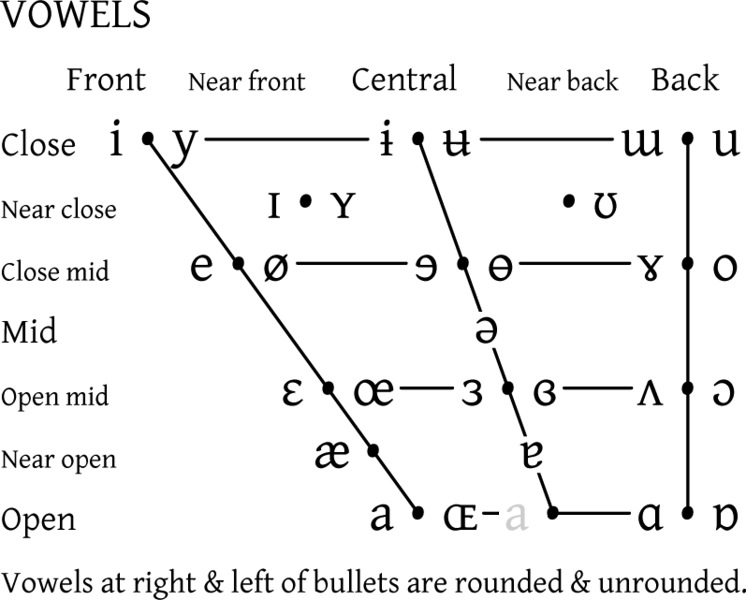

If you want to avoid accidental rudeness or embarassing dad-like humor, take a look at the IPA vowel chart. Its trapezoidal shape is an abstract representation of the shape of your mouth: the corner at /i/ represents your top lip, /a/ the bottom, /u/ the top of the back of your mouth, and /ɒ/ the opening of your throat.

What the vowel chart depicts is where the highest point of your tongue is in making any of these sounds.

Let’s take the sounds in the English words ‘too’ and ‘see’. Make the vowel sounds: ‘oooooooo’ /u/ and ‘eeeeeeee’ /i/. Now, if you alternate back and forth between them – oooooooeeeeeeeeooooooeeeeeee, sort of like the sound of an approaching ambulance – you’ll feel your tongue moving, like it’s doing the wave in your mouth. At /u/, its highest point is in the top back, and at /i/ it’s highest in the top front. The sounds in ‘too’ and ‘see’ differ only slightly in their physical articulation: /i/ is more fronted and /u/ is backed.

The IPA vowel chart shows you how to produce any vowel sound by combining its main ingredients. While there are some other, slightly more complicated aspects of vowels (like tension and nasalization), here we’ll focus on the three principal parts:

Frontness: When you move from /i/ to /u/, you’re going from front to back. It’s the same difference between the /æ/ in ‘sad’ and the /ɑ/ in ‘saw’. The horizontal position of your tongue in your mouth is called frontness or backness, and it’s super intuitive: front vowels are made with the tongue curved up in the front of the mouth, and back vowels are made with that high point in the back, closer to the throat. When the peak of your tongue is somewhere in between these extremes, it’s a central vowel.

Height: If frontness is the X-axis of vowel articulation, then height is the Y. If you move from /u/ to /ɑ/, from the sound in ‘too’ to the one in ‘saw’, you’re now descending vertically, from high to low. Just like frontness, this one makes a lot of sense: high vowels are made higher in the mouth, and low vowels down low. The middle ones are called mid vowels.

Rounding: It’s not all about your tongue – the lips get the final say on what vowel comes out of your mouth. Starting again from the same /u/ sound in ‘room’ and moving to the /ʊ/ in ‘rum’, your tongue stays the same, and it’s your lips that do the talking. Rounded vowels are made with puckered lips, like /u/ and /o/ in ‘too’ and ‘toe’ in English. Unrounded are all the rest, with relaxed lips.

Figuring out new vowels

Knowing where your current vowel inventory takes place in your mouth is sort of interesting, but isn’t immediately helpful: unlike their simpler consonant cousins, vowels aren’t precise enough to just ‘get’ by figuring out something as concrete as place and manner of articulation.

When I’m working on a new language, I start by identifying the vowels I lack, finding their closest equivalents in a language I do speak, and then figuring out the difference between that vowel I’ve already got down and the one I’m reaching for.

If you order an omlette du fromage in Paris, that du shouldn’t really sound like your English ‘do’. This is a high, front, rounded vowel in French: /y/. As an English speaker, there are two easy paths to ordering your omlette with native-like precision.

The first and maybe more natural path is starting with the vowel that it sort of sounds like in English: the /u/ in ‘do’. So what’s the difference between ‘do’ and du? That’s right: frontness! Push that already-rounded /u/ sound in ‘do’ right to the front of your mouth, and voila.

The second is the less intuitive but easier route. French rounded /y/ is, believe it or not, nearly exactly the same sound as /i/ in English ‘eat’. The only difference is rounding. If you eat meat in the street with rounded lips, then suddenly you’re dining roadside with a heavy French accent, because you’re using the same sound in du.

Vowels are notoriously hard to get right in a foreign language, and are often the source of the giant NOT FROM HERE sign that falls out of your mouth every time you speak. But with the IPA, a little studying, and some practice, you can have a nice conversation about the beach without offending a single person in the room.

The last step toward perfect pronunciation in a foreign language is phonetics, the infinitessimal details that define native pronunciation. In my next post for Transparent Language, I’ll share how you can use the principles of the IPA and phonology to pin down why your ‘perfect’ pronunciation isn’t quite perfect.

If regular old consonants and vowels are too easy for you, head to Part 3 to work on phonetics and really start speaking like a native!

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Jenny Gray:

This is the reason why I created and patented my product. Once you master the vowels, all the rest just aligns. Then you can develop structural rules and comprehension. The CEFR is based on oral communication in which sounds are key – to be understood wherever the language is spoken.

Thank you for reinforcing how I teach language.

Merci!

Ikar.us:

I’d have thought the most distinctive difference was that the vowel in bitch is short and in beach it’s long!?

Jakob Gibbons:

@Ikar.us Ah, Ikar.us, this is a really common misconception. There is actually no distinction in vowel ‘length’ in English, it’s a term that is used differently (and many would say incorrectly) in American phonetics. If you hold the /I/ sound in ‘biiiiitch’ longer, it’s still not a beach, but just a really long bitch 😉

The actual distinction between these two is one of vowel ‘tension’: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tenseness.