Why the Anti-Mistake Culture is Detrimental to Foreign Languages Posted by meaghan on Oct 18, 2017 in Archived Posts

What’s the best thing you can do to improve your language skills? Make mistakes.

The Problem With Anti-Mistake Culture

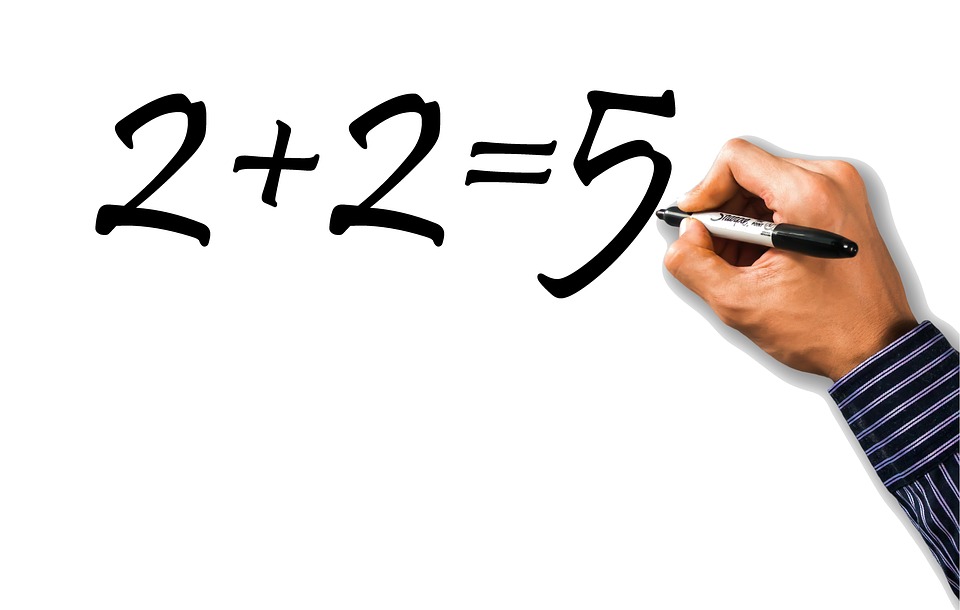

In an article on Medium, entrepreneur Catalin Matei describes what he calls the “anti-mistake culture”, the societal expectation that making mistakes is a bad thing, something to punish. One vivid example to which anyone can relate is the discouraging red ink on school assignments.

Matei points out that “Meaningful learning happens when trials and errors occur naturally and logically. Children should be able to make mistakes as often or as necessary to understand and learn what they are working on and how to understand it better.” This is an extremely valuable realization for language learners, individuals for whom not making mistakes is the biggest mistake of all.

The Benefits of Mistake-Driven Learning

Mistakes mean action. Saying something silly, mixing up tenses, or using the wrong word might seem like a step backward, but it’s actually forward progress. It means you’re using the language—always a good thing—and you’re identifying areas of weakness. It’s hard to get better if you don’t know where to improve. Mistakes can pave your path forward.

Mistakes mean comprehension. If you can identify your own mistakes and find the solution—the correct word, pronunciation, etc.—you are more likely to commit that information to your long-term memory than if someone feeds you the answer.

Mistakes mean repetition. When you know you’re doing something wrong—using the wrong auxiliary verb or butchering some tough pronunciations–you’re more likely to practice and get it right. Repetition and review is critical for language retention (it’s why spaced repetition algorithms are so common in language learning technology).

Mistakes mean imperfection. Embrace that fact, because you will never be perfect in your adopted language or be done learning it. When you stop pursuing perfection, you’ll be a lot less frustrated or disappointed and a lot more pleased with small victories and steady progress over time.

Mistakes mean confidence. If you’re out there being vulnerable in your adopted language, talking to anyone who will listen and accepting constructive criticism, it means you’ve already made a huge step in the right direction: you’re not afraid to use the language!

How can you battle the anti-mistake culture?

Educators can encourage and leverage mistakes to make them a regular part of the learning process. You can give learners the opportunity to correct their own mistakes, such as offering points back on corrected quizzes. You can also keep it anonymous and analyze the most commonly made mistakes as a class.

Individuals can give themselves the same grace when it comes to messing up. Keep a mistake journal and review it every so often, ask speakers of the language to point out mistakes, and never let yourself be embarrassed or intimidated by saying the wrong thing.

Matei said it best when it comes to mistakes: “At some point, you need to expose yourself to failure and avoid sticking only to the thing that you feel you’re already good at. Are you willing to succeed? Then fail.”

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Anghel Ion-Aurel:

Cătălin Matei is a ,,he”, not a ,,she” and his point of view is the opposite of what I was taught at school. The truth is in the middle of the matter.

Transparent Language:

@Anghel Ion-Aurel Yikes, thanks for the correction!

Virginia Lowe:

Just read that a Museum of Failures is opening in Los Angeles! Thanks for this article I agree that it’s important to provide an environment where learners can be allowed to have fun learning and play with language. It’s very natural when we consider how all people learn language developmentally from childhood.

M.A. Barry:

Metei’s point of view is correct.

When I was just about to start learning English as a second language, my first grade was # 1 in grammar. But today, I’m a teacher of both English and French.