Should all foreign language instruction be proficiency-based? Posted by Transparent Language on Jun 25, 2018 in Archived Posts

We write often about language proficiency on this blog, from the different scales used to measure proficiency, to how you can assess your own proficiency level, and even how vocabulary size relates to proficiency level.

A language proficiency scale provides a very useful, standardized measurement of one’s abilities. Proficiency, however, is not just a measure of what you already know or can do in a language—proficiency is a framework that can be leveraged to guide and organize what and how you learn.

Proficiency-based language instruction stands in contrast to traditional language programs in terms of organization and instruction.

Organization: What does a proficiency-based language program look like?

Most traditional language classes progress along school grade levels (such as moving from “French 1” in 6th grade to “French 2” in 7th grade) or allow learners to self-enroll into classes with generic misnomers (like “Beginner French”). This approach provides very little transparency to instructors or learners.

What if language classes and training programs followed a well-defined, communicative-focused proficiency scale to organize and instruct classes? One K-12 school is doing just that. The Latin School of Chicago recently transitioned from a grade-based model to a proficiency-based model, with students being grouped together by their ability levels rather than their age or grade level:

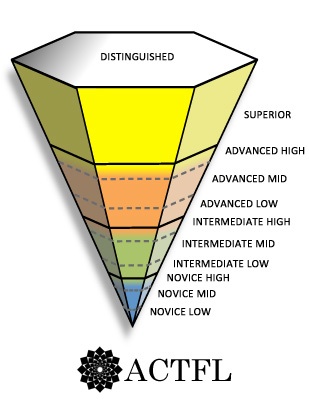

“This helps them learn at a pace and level that fits them best, but it stands in contrast to the traditional model where students progress to the next level—for example from Spanish 1 to Spanish 2—by default after a year of study. In this new model, students progress through six levels [of the ACTFL scale], starting at ‘Low Novice’ before gradually moving into ‘Intermediate’ and potentially ‘Advanced’ levels.”

Instruction: How does instruction differ?

According to the Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (CARLA), one of the principle implications of proficiency-oriented instruction is to design curricula and teach “specifically for proficiency outcomes balancing the three components of proficiency: content (the topics of communication), function (a task; the purpose of a spoken or written communication), and accuracy (correctness or appropriateness in pronunciation, writing, grammar, culture, and vocabulary choice).”

The proficiency-based classroom does not neglect vocabulary or grammar, the typical pillars on a traditional classroom. Learners need a command of grammar and a wide breadth of vocabulary to communicative effectively in a language. Instead, the proficiency-based approach employs these components in the context of productive, communicative activities.

This can take shape differently depending on the ages, proficiency levels, and even location of the learners. In our online training programs, proficiency-based learning looks a bit like this: learners are assigned an authentic text with key words and phrases (content) to master before class. They then come to class ready to produce that knowledge via skits, debates, and other communicative activities (function). An instructor guides the in-class activities and provides feedback as needed (accuracy).

Proficiency-based language instruction emphasizes communicative proficiency.

A major differentiator—and strength—of proficiency-based instruction is the emphasis on communicative proficiency. The focus is less on what students know about the language (memorized grammar rules, conjugation tables, etc.) and more on what students can do with that knowledge, from a functional, communicative perspective.

A traditional curriculum, for example, might present “French 1” learners with common vocabulary and fixed phrases, organized into topical units like “shopping” or “transportation”. This knowledge might be tested via a written vocabulary quiz before moving on. An ACTFL-aligned, proficiency-based curriculum would take it one step further, measuring not only that learners memorize the words, but that they can also produce that knowledge in basic conversations.

For example, a learner testing at the Novice Low level would be able to “name very familiar people, places, and objects using practiced or memorized words and phrases, with the help of gestures or visuals”, whereas a Novice High level learner would be able to “present on familiar and everyday topics, using simple sentences most of the time.” (Can-do statements taken from ACTFL’s 2017 Proficiency Benchmarks).

The difference between even the sub-levels of ACTFL’s Novice level is not subtle—producing short strings of familiar words vs. using short but correct sentences. But a non-proficiency-based language program fails to capture that difference in communicative proficiency among beginners in the “French 1” class, sending them on to “French 2” without measuring their communicative abilities.

Proficiency-based learning holds learners accountable—and encourages achievement.

Language proficiency is not about agency or accountability, but it certainly can set the stage for emphasizing those qualities to the benefit of instructors and learners.

Because class assignments are determined by ability rather than grade level, learners only move up to the next level when they can demonstrate they have become proficient at certain communicative skills prescribed at that level. In short, learners are held accountable for their own progress.

While the Latin School in Chicago noted this is a potential source of stress for learners, particularly in such a competitive environment, one Chinese teacher identified this sense of accountability as an advantage:

“I loved seeing the class’s eagerness to write more, their openness to communicate and the girl’s sense of agency to hold herself accountable for achieving the learning objectives. In many ways, the proficiency-based model facilitates the development of these characteristics. The model guides teachers in organizing instruction around proficiency goals that are aligned with the students’ abilities. These goals also make it easier for students to check in their own learning and see a purpose in practices that we do everyday.”

Professional programs center instruction and results around measurable communicative standards, for good reason.

When training or hiring a bilingual employee, organizations need to know what that employee can do in the language—it’s not about a letter grade, it’s about negotiating a contract with an overseas buyer, translating marketing materials to reach an international audience, or collaborating with foreign partners.

Well-defined standards derived from a language proficiency scale such as the ILR or ACTFL clearly articulate a learner’s communicative abilities. This is important for measuring progress, but also for signaling skill levels to universities or employers; earning a B+ in “French 2” means significantly less than moving from Novice High to Intermediate Low, or from a 2/2 to a 2+/2+.

For this reason, many professional language programs rely heavily on assessments (based either on ACTFL or another well-known scale such as the ILR or CEFR scales) to better group learners together and instruct according to their abilities and needs. The State Department’s Foreign Service Institute (FSI) champions this approach, and rightfully so: American diplomats are expected to reach a defined proficiency level (usually a Speaking 3/Reading 3 on the ILR scale) before reporting to their overseas assignments.

Likewise, the Defense Language Institute (DLI), the U.S. military’s premiere language training school, uses proficiency assessments to measure the “mission readiness” of its students both during instruction and throughout their careers. The Defense Language Proficiency Test (DLPT) is given annually to monitor linguists’ ability to function in real-life situations. Regardless of classroom grades, DLI students are not allowed to graduate without achieving a L2/R2 score on DLPT.

Many of our own professional programs align with ILR scale, which we leverage to create level-appropriate content and assignments to help professional linguists sustain and improve their communicative skills.

All language programs can incorporate elements of proficiency-based instruction and assessment.

From an administrative side, transitioning to proficiency-based teaching can be a lot of work: students’ proficiency must be measured often and accurately, schedules must be meticulously coordinated, and the assessment system must be clearly explained to learners who are accustomed to moving up a level each year, regardless of proficiency or performance. Nonetheless, the outcomes of proficiency-based instruction more than justify the administrative efforts.

A complete overhaul of language education in the U.S. is unlikely, but support for proficiency-based, communicative-focused instruction is rising. More than 30 states (and Washington, D.C.) are already on track, awarding high school graduates a Seal of Biliteracy on their diplomas if they can demonstrate proficiency in two languages. Proficiency in this situation is typically measured by the score on the AP exam, which includes interactive with authentic materials and producing the language through both interpersonal and presentational writing and speaking tasks. Recipients are required to score a 3 on the AP exam (anecdotally equivalent to Intermediate-Mid on the ACTFL scale).

Build vocabulary, practice pronunciation, and more with Transparent Language Online. Available anytime, anywhere, on any device.

Comments:

Laura McClintock:

Great insight! I like how the focus here deals with ability levels and what students can actually do with the language in a practical setting. I like the fact that more and more schools are moving toward this model. If you are interested in reading more about relevant issues in the World Language class, you might enjoy my blog: teachinginthetargetlanguage.com. Thank you for this post!

Eugene Sedita:

Sans doute, the best online language resource I’ve found.

Go no further; your search is over.